Wayne Rebhorn’s Translation Brings Boccaccio’s Decameron to Life

On the morning of Sept. 11, 2001, Professor Wayne Rebhorn was preparing to teach Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron when news came of the terrorist attacks in New York City. He wondered if he should go ahead with the class, or cancel in light of the tragedy.

“Then I thought, ‘the stories in the Decameron are told by a group of young people coping with ultimate tragedy and death,’” Rebhorn says of this classic work, written in the midst of the Black Death that swept 14th century Europe. “They cope with tragedy by going into the country and telling stories. It is life affirming.”

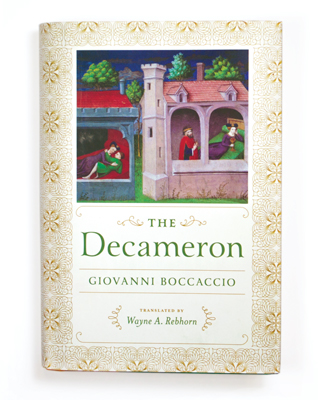

WW Norton; Reprint edition, Dec 2014

By Giovanni Boccaccio, translated by Wayne Rebhorn, professor, Department of English

Boccaccio set his stories in an idyllic Tuscan landscape, where seven women and three men have fled from the horrors of plague-invested Florence. They agree to a plan to tell each other stories—100 in all—over a two-week period (taking the weekends off), with love the prevailing theme.

“Some of the stories are astoundingly funny,” says Rebhorn, a professor in the Department of English whose recent translation of the Decameron has received prominent and widespread critical acclaim. “But the stories also underscore the importance of using language well to enrich our lives. Horace said literature should be both sweet and useful—we want a good story, but we also want to learn about ourselves.”

And there is much we can learn about ourselves today from a man born 700 years ago in a time and place far removed from our own. However, since few of us are fluent in 14th century Italian, or well-versed in the customs and politics of that time, we need someone like Rebhorn to make these stories live for us again.

In his introduction to the Decameron, Rebhorn reminds us that the root meaning of “translate” is to take something across a border or a boundary, to bring that which is foreign or strange from one language and age into another. It is a daunting task he describes in terms of “puzzles;” the translator must discern the meanings of individual words and phrases as well as the syntax, that is, the particular arrangement of a sentence. The Decameron presents a unique challenge because the very complexity and order of the sentences is critical to Boccaccio’s message.

“That’s the challenge to a translator: How to respect Boccaccio’s complication in language without making it clumsy,” Rebhorn says. “It is a linguistic puzzle to translate both complexity and wordplay, to get it both literally and figuratively correct. You have to respect the aural rhythms in the language. It is difficult work, but I also find great pleasure in this linguistic challenge.”

For example, the book’s narrators, who come from polite society, speak in formal, complex sentences, as do the characters in their stories of courtly love, while simpler, colloquial language is used in the stories of peasants and craftsmen. This diversity of styles in the stories is important; their colorful celebration of life in all its richness, texture and contrast is precisely the balm our narrators need in an ashen world of disease and death.

This is a quality that sets Rebhorn’s translation apart from others and draws praise from reviewers. Joan Acocella’s lengthy review in the New Yorker (Nov. 11, 2013) refers to Rebhorn’s translation as “a thoughtful piece of work, with populist intentions…with a concern for the common reader, he has tried to make the slang sound natural, and he succeeds.” Historian and writer Steve Donoghue, writing in The Quarterly Conversation (Dec. 2, 2013) proclaims “Rebhorn is the first Boccaccio translator in 300 years to understand so clearly that the main thing being celebrated amidst all these fevered couplings is “intelligence in all its forms.”

By writing his great work in the local Tuscan dialect, Boccaccio was doing for prose fiction what his mentor Petrarch was doing for lyric poetry and Dante for epic poetry in the Italian language. For this reason they are collectively called le Tre Corone, the “three crowns” of Italian literature.

As feudal states gave way to nation-states and the rise of cities, the Decameron signaled the waning of the Middle Ages and the rise of Renaissance humanism. Boccaccio’s stories, especially in the Rebhorn translation, are very human indeed.

“Boccaccio demonstrates the power of storytelling and how it can inform our lives. You can take care of yourself in life and be successful if you know how to tell a good story,” Rebhorn says. “But it also reminds us of the joys of simply being alive. If it’s nothing else, the Decameron is just plain fun to read.”