The nation that will insist upon drawing a broad line of demarcation between the fighting man and the thinking man is liable to find its fighting done by fools and its thinking by cowards.

– Colonel Sir William Francis Butler, in Charles George Gordon

Though the National Defense Act of 1916 created the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC), to ensure uniform, high-quality officer training for the United States Reserves and National Guard, limited resources from the U.S. War Department during the World Wars and unwavering opposition to introducing “militaristic” courses to an otherwise civilian campus would block The University of Texas at Austin from establishing its own Army ROTC for nearly three decades, when World War II would prove, beyond question, the value of ROTC.

Duty, Honor, Education

After WWII, the UT Austin campus “swarmed with flight jackets, pea coats, cuffless khakis, Ike jackets, GI shoes and other military apparel,” wrote Don Knoles in a January 1960 issue of Alcalde. But it wasn’t their apparel or even the “shiny little discharge button” on their lapel that distinguished these students from the rest. It was their demeanor.

“They measure what you tell them and weigh it against the terrible insights they acquired into human nature,” said one professor quoted in the article. “They work harder and make better grades but above all they bring with them a desire for knowledge. Never has teaching been more rewarding or more demanding.”

Thanks to educational benefits from the 1944 Serviceman’s Readjustment Act (the G.I. Bill), from 1945 to 1946 UT Austin’s enrollment rose from 7,027 to 17,108 — 10,849 of whom were veterans. By then UT Austin had also established and was running its Naval ROTC unit — which UT football Coach Dana X. Bible had relied heavily on for manpower during WWII when the draft left behind only three UT lettermen with physical ailments to play, writes UT Army ROTC and history alumnus John Boswell (1969) in his historic account of UT Army ROTC, Texas Fight: The History of ROTC at The University of Texas at Austin, 1947-2017.

While the influx of students after WWII certainly created concerns over housing, dining and class schedules, servicemen were finally being smoothly integrated on a campus that had, like much of the nation throughout the 1930s, taken a tone of animosity toward the military, capping a three-decade-long struggle to establish an ROTC unit on campus.

“In retrospect had the University started ROTC in 1937, the Class of ’41 would have contained enough officers to lead 5,600 enlisted men or nearly two regiments of Infantry,” read a six-page, typed document, titled “Army ROTC at The University of Texas—A brief history, 1947-1957.” The document was discovered in a copper box time capsule from 1957 during the demolition of Russell A. Steindam Lecture Hall in 2011.

Army ROTC comes to UT

Even without the UT Army ROTC unit, Texans were voluntarily enlisting in greater numbers than any other state by 1941, and by 1943 there were 750,000 Texans in uniform, including two of the most decorated soldiers among the 16 million Americans who served, writes Boswell. He notes that there were so many Texans in the Canadian Air Force that it was referred to as the “Royal Canadian Texas Air Force.”

Even without the UT Army ROTC unit, Texans were voluntarily enlisting in greater numbers than any other state by 1941, and by 1943 there were 750,000 Texans in uniform, including two of the most decorated soldiers among the 16 million Americans who served, writes Boswell. He notes that there were so many Texans in the Canadian Air Force that it was referred to as the “Royal Canadian Texas Air Force.”

“I know how Texas boys feel. I am one of them,” said Congressman Lyndon Johnson in a floor speech on Aug. 8, 1941. “Texas boys come from a race of men who fought for their freedom at the Alamo and Goliad and San Jacinto… Texas boys prefer extended service now to slavery hereafter and our best insurance against slavery is the best trained and equipped Army anywhere in the world.”

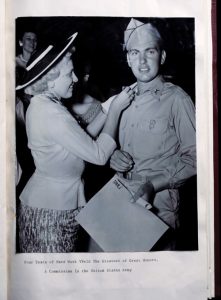

The changing tides prodded the UT Board of Regents to pressure UT President Homer Price Rainey (1938-1944) into establishing ROTC units on campus, beginning with Naval ROTC in 1940 and followed by UT President Theophilus Painter’s (1944-1952) efforts to secure an Army and Air ROTC unit on campus after the war’s end, when the War Department would be better equipped to provide the proper resources.

“It is a great personal satisfaction to me and to thousands of other Texas Exes to see ‘old Texas’ take this step and I want to congratulate you and your faculty on your foresight and sense of duty,” wrote Texas Military District Brigadier General K.L. Berry in response to Painter’s 1947 application, which was approved by WWII hero General Jonathan M. Wainwright on April 25, 1947.

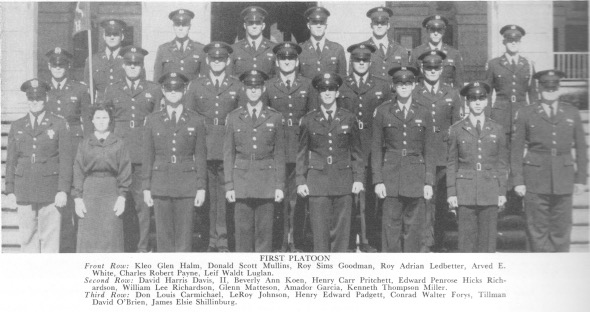

The first UT Army ROTC Battalion formation took place in September 1947 with 210 cadets, just before Painter and the new ROTC leadership finalized the design of the UT Army ROTC shoulder patch and the Battalion’s first flag with the motto ‘Ex Vigilantia Pax’ – From Vigilance Comes Peace.

In Peace Prepare for War

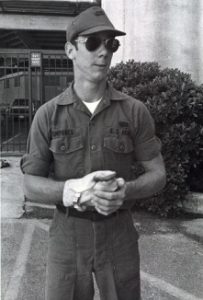

With WWII and the Great Depression left behind, the 1950s brought more support and respect on campus and nationwide for the military. At this point, UT Austin was the only Texas school with all three branches of ROTC, and enrollment was high, with an average of 416 enrolled each year — a likely consequence of the draft, influencing many male students to “avoid Korea,” where William J. Browning, one of UT’s first commissioned officers (1949), was killed in action.

The decade also brought the end of segregation in both the graduate and undergraduate schools in 1955 and 1956, respectively. In 1961, Col. Leon Holland, son of a career soldier and a Wilberforce Army ROTC graduate, was the first black cadet to receive commission through UT Army ROTC. Boswell writes that while Holland experienced hostility on campus, including an incident where a cross was burned in front of his dorm, he found comradery with his ROTC peers.

“I never had to look over my shoulder when I was around them, and I looked forward to ROTC classes and drill,” says Holland, quoted in Texas Fight, which also highlights a 1959 summer camp incident at Ft. Lee, Petersburg, Virginia, where a restaurant refused service to Holland because of his race, and all of his fellow Longhorn cadets walked out with him.

Though ROTC units were slowly becoming more diverse by race, UT Army ROTC would remain all male until 1974, Boswell says, describing women’s involvement as “Sponsors” or “Cordettes” as similar to the roles and mentality many women at home assumed while men were abroad in WWII. He thought of these women as “daughters of WWII,” and the cadets as “sons of WWII.”

“We were the children whose fathers fought in WWII,” says Boswell, recalling his time in ROTC in the 1960s. “Along with their presence at ROTC drills and various social functions, the Cordettes would carry out public service missions, including visiting wounded soldiers and writing letters to G.I.s in Vietnam. There was a real comradery between us.”

Be All that You Can Be

Vietnam sparked another anti-war movement across the country in the 1960s, and ROTC once again “became a target for anti-war leftists,” Boswell says. “It’s like they were picking up the ‘30s commentary and regurgitating.”

Boswell recalls Thursday drill back on the freshman field, where demonstrators would throw water balloons and “use a lot of foul language.” The push to get ROTC off campus was evident in “hostile letters” written in The Daily Texan. “But we were told in no uncertain terms by our officers that if we retaliated, we would be kicked out,” Boswell says, adding that the attacks strengthened the cadets’ resolve.

“I don’t know anyone in ROTC who liked war. We saw it as a duty,” Boswell says. “The training wasn’t theoretical. We knew we’d better get ready. It was very serious. We didn’t talk a lot about the war, whether it was right or wrong. The attitude was pretty much, when you’re in the military you follow legal orders. We didn’t debate it.”

Four Army ROTC cadets were killed in Vietnam, including Russell A. Steindam, a Medal of Honor recipient who had thrown himself on a hand grenade to protect his platoon. UT also remembers the supreme sacrifices of John K. House (1967), killed in action in 1968, Roy Nelson (1969), killed in action in 1971, and Marshall Williams (1967), who died in Vietnam in 1971.

Today’s Army Wants to Join You

The 1970s witnessed the end of the draft and a dramatic downsizing of the Army and ROTC units on U.S. campuses. Enrollment for UT Army ROTC dropped from 273 in 1970 to 46 in 1975. “Even though the numbers were dropping, the Department of Defense wanted to keep ROTC because they wanted college-educated, well-rounded people in officer positions. And they wanted the civilians to be connected to the military,” Boswell says.

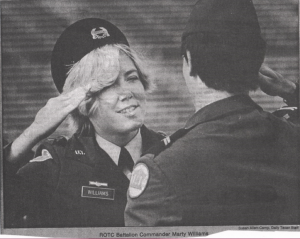

But the decline in enrollment opened the door for female officer training, which many nursing majors took advantage of to gain training for the Medical Service Corps, Boswell says. By the end of the decade, 13 female cadets comprised 18 percent of the Longhorn Battalion, a similar percentage to today’s battalion. And in 1981, Marty Williams became the first female Battalion Commander at UT.

“I don’t think the Army will take the first step in putting women into combat. Society will have to do that,” Williams is quoted in Texas Fight. “But the military can show society that men and women can work together… As a civilian nurse I wouldn’t get the opportunity to jump out of airplanes. Who knows, maybe someday we’ll have nurses jumping behind enemy lines to give shots.”

The 1980s saw an enrollment rebound with a resurgence of patriotism due to the strong support U.S. President Ronald Reagan had for the military. But enrollment would decline again in the early 1990s as Desert Storm deterred some potential cadets from joining for fear of the possibility of going to war.

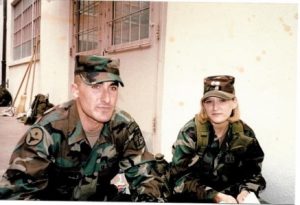

In the 1990s, women continued to gain traction up the ranks of the Army. In 1995, Lt. Col. Brenda Alicea became UT’s first female professor of Military Science, and the first to press cadets to keep up with national and world events by instituting current events classes led by UT experts on the 1990s Serbian-Bosnian crisis.

“Education can help instill a moral and global compass in military leadership. It’s not just about brawn, you have to be thinking,” says Boswell.

The last UT Army ROTC alumnus to date to be killed in action was Capt. Orlando Bonilla (1999), who was killed in 2005 while piloting a helicopter during combat operations near Baghdad. He received both the Air Medal and the Bronze Star.

No Mission Too Difficult, No Sacrifice Too Great, Duty First

At a reception celebrating UT Army ROTC’s 70th anniversary on April 25, 2017, Lt. Gen. Lawson W. Magruder III, the highest ranking UT Army ROTC graduate (1969) and son of the first alumnus to serve as professor of Military Science, Col. Lawson Magruder Jr. (1967-1971), applauded current cadets and alumni for their strength of character and even greater sacrifice.

“Sacrifice is doing what my soldiers, unit and country expect of me; enduring optimism despite adversity,” Magruder says. “Success depends on the character of the soldier as much as the competence of the soldier. Our strength of character is defined by our personal values combined with Army values… we are the sum of those who’ve loved us and those who continue to.”

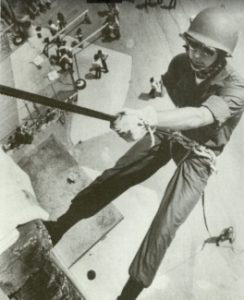

The anniversary also served as a celebration of the year’s accomplishments. Just a few weeks ago, the Ranger Challenge team clinched first place in the ROTC division of the Sandhurst Military Skills Competition, a 25-mile, full-pack trek that tests basic soldier and leadership skills. The Sandhurst win put UT Austin at No. 1 out of 273 ROTC programs in the country, an incredible feat for a team derived from a comparably small program, said Lt. Col. David Zinnante, chair of the Department of Military Sciences and the second UT alumnus to serve as professor of Military Science.

“We don’t have any one-trick ponies in ROTC,” Zinnante said. “These students are involved across campus in pretty much any organization you can think of. That involvement is what’s going to help us serve our nation and ensure ROTC remains an integral part of the university going forward.”

His final remarks to the cadre were to “be better today than yesterday, and better tomorrow than today.”

The current cadets expressed gratitude and admiration when reflecting on the program and the soldiers of the past who made UT Army ROTC what it is today. Cadet Cole Stevens, a senior in public relations, had this to say as he recalled the events of the 2016 Veterans’ Day football game:

As we were walking from the Veterans’ Day tailgate to the stadium, we walked past Frank Denius Field, the football practice field named for the Longhorn legend and our battalion’s biggest supporter. I remember standing on the field inside the stadium, listening to the marching band being led by Cadet Andrew Repetski playing tuba, followed by the Texas Army color guard team to present arms at center field, while Cadets Sterling Burdine and Rebecca Edwards sang the National Anthem in front of 100,000 fans. I looked up to see a formation of F16s fly over, followed by the Golden Knights parachute team piloted by Texas Army graduate Capt. Ben Fizzell. Right after the football team took the field, I saw Cadet Kyle Hrncir suited up at linebacker warming up with the team. On the Jumbotron there were pictures of Col. Leon Holland, Texas Army graduate and a member of UT’s Precursors, and Lt. Gen. Lawson Magruder III, a member of the Ranger and ROTC Halls of Fame. Both received huge cheers from the crowd and, as I took all of this in, I couldn’t help but think: Wow, we kind of run this place.