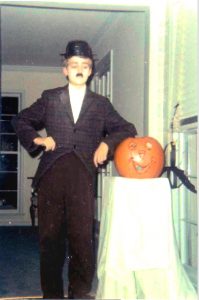

On Halloween night, 13-year-old Rik Gern grabbed his wooden cane before setting off to trick-or-treat around the neighborhood as Charlie Chaplin.

Delighted at the sight of a child festooned in a black bowler and matching mustache, families welcomed him inside to show off his foolproof impression to granny.

“Look, Nana! Look who’s here to visit you,” Gern laughs, recalling his introduction to elders who no doubt remembered the Tramp from years gone by. “I stayed in character the entire night. I would twirl my cane and twitch my little mustache; and I got a sense of how fun it was to be that character and to be entertaining.”

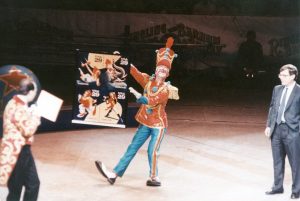

Today, you can find Gern at birthday parties, festivals and family reunions dressed as Bonzo Crunch, Austin, Texas’s “Fool at Large”—a career he launched full-time 40-years-ago when an advertisement for clowning classes on his college’s campus agitated his funny bone enough that he dropped out, joined a local clown group and ran away to the circus.

All Jokes Aside

His decision to pursue clowning came right around the time when the evils of John Wayne Gacy, who occasionally dressed as a clown called “Pogo,” came to light. Gacy would lure his victims into his home through the promise of electrical work, Gern says. From 1972 to 1978, Gacy sexually assaulted and murdered at least 33 young men.

“My first show in clown makeup was at a children’s hospital, and right as we were about to perform, the television interrupted with breaking news about the bodies found in John Wayne Gacy’s basement,” Gern says, still astonished. “And then, they introduced us.”

Frustrated, Gern explained that Gacy was not a clown. He merely dressed as one a couple times a year for neighborhood events. “But the idea of a ‘Killer Clown’ captured the imagination in a horrific way,” Gern says.

“It was a turning point and a strong event to make clowns seem negative,” he continues.

Then Stephen King’s It played on that fear with an amorphous villain who would assume several manifestations based on his victim’s fear, a clown named “Pennywise” being the most notable. “It’s a creative character, and I don’t object to work like that. Kudos to Stephen King,” Gern admits.

The scary clown-thing is simply a new trend, Gern assures. “You get a lot of copycats because it’s easy to combine innocence with horror.”

It has become hip to be scared of clowns, he says. “But I don’t think it can go much further than it has. I think people will start to get into the look of the scary clown more than they will fear it, and I predict the return of the trickster clown — you can already kind of see it in the Juggalos.”

Bag of Tricks

The Juggalos are fans of the self-dubbed “most hated band in the world,” the Insane Clown Posse. The rap group’s following of misunderstood outsiders share a common thread of feeling belittled by others for their weight, social class or physical appearance.

Gern’s right about the Juggalos: they share some lineage with earlier, more mischievous pranksters that made a living goofing off for royalty and the elite. Many of these performers were often low-class oddballs, and pop up in history as early as 2500 B.C. in ancient Egypt and as late as medieval Europe.

In places like Rome in the late Republic (1st century B.C.), professional pranksters and dinner entertainers, called scurrae, fell into their line of work by way of physical oddities — “freak shows, in other words,” says University of Texas at Austin distinguished professor of classics Karl Galinsky, citing a boastful contest written about by Horace where two scurrae—also called gelotopoioi or “laughter makers” — hurl low-brow insults at each other, centering on physical deformities, low status and animal-like qualities.

While these performers were not considered equals by elites, their positions within the households allowed them to advance socially. “They could make careers as social companions — and as freeloaders — to upper-class Romans,” Galinsky says.

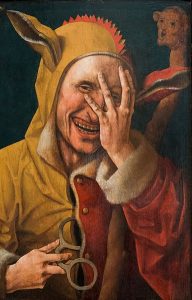

Similarly, European jesters were afforded the unique freedom to speak shrewdly and outwit those of higher social status, all in the name of good fun and social justice. They made a living of dancing on the line of satire and insult, humanizing the decisions of the court, and “at worst, they could pay with their life if they failed to get a laugh,” Gern says. But most were cherished deeply by their royal houses and even sought after for advice on social issues.

Act the Fool

These historic characters and the essential role they played were first celebrated in the theater—the most famous rendition being the Shakespearean Fool.

“Clowns were a traditional part of the early modern theater, and gradually morphed into the more erudite ‘fool’ after about 1600 — hence, the fool in King Lear, who seems educated and part of the world of the court,” says UT Austin English professor Douglas Bruster. The character often appeared as a clever commoner, who said things people of that class shouldn’t get to say.

Similar to that was the 13th century Chinese “chou,” identified in the theater by a painted white patch around his eyes and nose and distinct from the cast due to his liberty to improvise, offering comical, albeit political, critiques through exaggerated actions.

But, perhaps the greatest influence on the modern clown stemmed from 16th century Italy’s commedia dell‘arte, says Robert Di Donato, who recently completed intensive clown training after graduating last May with a degree in Theatre & Dance from UT Austin.

“Clowning became a thing in Italy during the Renaissance with these improv troops in which the entire cast wore masks,” says Di Donato, who filled his undergraduate concentration with courses in Italian from the UT Austin College of Liberal Arts. “From then, clowns were incorporated more frequently as these buffoon characters that are a little fun and a little simple.”

“I like to describe clowning as how you would grow up as an adult if you were never told ‘no’ as a kid,” Di Donato laughs, adding that it’s a form of acting based in the body that forces the actor to be more in-tune and honest with both his audience and himself.

“First and foremost, I learned that people want to see you tell the truth,” Di Donato says. “As soon as you start lying the audience will catch on, and you’ll lose their interest.”

More and more actors today are attending clowning school, Di Donato says, crediting his therapeutic experience as ridding him of stage fright and making him more perceptive.

“Clowning is about observing other people, observing yourself, and observing how others observe you,” Gern echoes, almost melodiously. “It’s observing through a whimsical eye.”

Clowns revealed exactly how astute they were as the character became integrated into circus performances.

Send in the Clowns

“It’s the person who speaks the truth behind the mask,” says UT Austin American studies professor Janet Davis.

Clowns were first introduced to American society by way of the traveling circus in the late 18th century as a fundamental element of the show, she says. Back then, circuses were more intimate, allowing (what was later referred to as) the “talking clown” to be heard.

“They were very much social critics — sensitive to the culture of the towns they would visit, crafting their dialogue and jokes around local news and politicians,” Davis says, likening them to stand-up comedians.

Perhaps the most popular political clown was Dan Rice, Gern says — or as biographer David Carlyon calls him “the most famous man you’ve never heard of.” By the mid-19th century, he was so popular, he ran for President of the United States. And if you look closely enough, you can catch a glimpse of the late fool in the image of Uncle Sam, for which he was one of the main models.

Much of the circus clown image was inspired by Joseph Grimaldi, who delighted audiences across England with his buffoonery in the 19th century.

“It’s hard to say why one person captures the imagination,” Gern says, pointing out that part of his patterned costume is a tribute to this famous clown. “He worked like crazy, and he was also very clever and imaginative.”

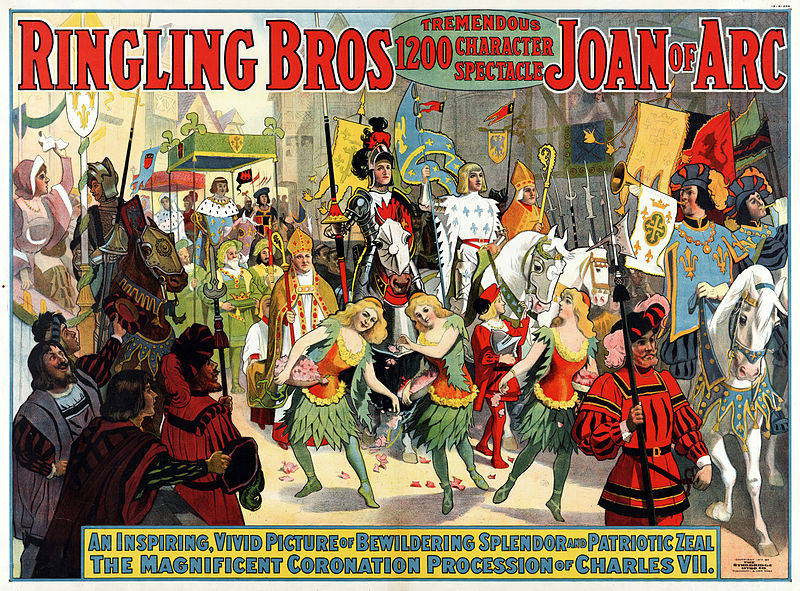

Still today, clowns — who are often referred to as “Joeys” in his honor — mimic his classic white face, a look that became really crisp and bold as circuses transformed from one-ring to three and took to the steel rails lining the U.S. landscape.

A small show that was once exclusively for adult audiences became an enormous venue for family-friendly entertainment, as the big tops welcomed in crowds of more than 10,000 by the late 19th century, Davis says. In turn, “the clowns lost their voice,” she adds.

“The 20th century saw the flourishing of the pantomime clown,” Gern explains, adding that the bolder make-up was essential for audiences to read the clown’s emotions from far away.

The circus had entered an entirely new market of children’s entertainment and events were promoted as a safe, educational and wholesome experience for the whole family, Davis says — Gern adds that they also appealed to working-class immigrants who could attend the show and enjoy the clown’s silent humor as much as native-born, English speaking Americans.

“This all accompanies a larger shift in cultural history about the sacredness of childhood, and later, an influx of immigration from Eastern Europe,” Davis explains. “This is when we really see the clown transform into the child’s friend, and circuses began plastering the clown image all over their marketing materials geared toward children.”

Media Circus

Soon the image of the clown became “commercialized” and marketable in entities outside of the circus, Gern explains. As circuses began to fold, clowns sought work in advertising or television shows — Emmett Kelly being the most successful in the transition, he adds.

“All of the sudden you had a generation of people who saw images of clowns through the media more than in personal interactions,” Gern offers, describing how the marketed look became “overly cute” and ripe for critique.

Combine that with a general cynicism of the times,” Gern explains, drawing back to the temptation and ease of intersecting innocence with horror, especially when a story as successful as IT brought children’s fear of costumed characters to the forefront.

“Many little kids are also scared of Santa Claus at first,” offers Jacqueline Woolley, chair of the UT Austin Department of Psychology. “I think this and the fear of clowns may stem in part from the combination of children being taught to fear strangers and the familiar behavior and expectations surrounding interactions with both clowns and Santa. The disguise licenses or even encourages a level of closeness that wouldn’t be permitted from a stranger normally, like expecting a child to sit on Santa’s lap or hug a clown. This can be scary.”

She also suggests the concept of the “uncanny valley,” which describes how as a non-human entity approaches humanness it can get “creepy.” For children who are still learning to differentiate fantasy from reality, clowns who resemble humans but display obvious facial differences may fall into this valley, and hence create confusion that can lead to fear.

Woolley assures: It’s something most people grow out of.