New DNA tests may reveal your ancestry, but researchers urge caution when interpreting results

From 1892 to 1954, More than 12 million immigrants entered the United States through Ellis Island in New York Harbor. They left behind a huge repository of records that for many years has been the first stop for Americans researching their genealogy. More than 100 million Americans are directly related to immigrants who passed through the island.

Now an increasing number of people are turning to a new source of historical information for answers about their family history—their DNA. More than two dozen companies offer genetic tests that claim to link people to high-profile ancestors, such as Genghis Khan or the Irish warlord Niall of the Nine Hostages.

While the testing companies promise to unlock the secrets of your ancestry, researchers warn the science can be problematic. The tests also raise complex questions about identity and race. If you’re thinking about adding DNA testing to your repertoire of genealogy research tools, proceed with caution.

Deborah Bolnick, assistant professor of anthropology at the University of Texas at Austin, studies the tests and is following the budding trend closely. She questions the tests’ validity and reliability, and worries many people may be unaware of the underlying scientific assumptions on which the tests are based.

In the policy piece “the science and Business of Genetic ancestry testing,” which appeared in a recent issue of Science, Bolnick and 13 researchers from across the nation called upon the scientific community to better educate the public about the limitations of the tests.

“Consumers should know the limitations and complexities before they spend $500 thinking they’re going to find an answer to who they really are,” Bolnick says. “It’s much more ambiguous and uncertain than the testing companies make clear. these tests often make dubious assumptions and rely on limited databases of comparative samples, so there’s a large margin of error.” Home DNA test kits are available on the internet at a cost between $70 and $850 per test. With one swab of the cheek, participants mail in a sample of their saliva to a genetic lab for testing. They receive results in a matter of weeks. the two most common tests examine the paternally inherited Y chromosome (Y-DNA), which is passed down from father to son, and the maternally inherited mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), which is passed down from mother to child, both male and female. A third type of test (autosomal DNA) examines DNA inherited from both parents.

“With many of these tests, you’re only tracking one small part of your family tree,” Bolnick says. “For example, a mtDNA test can tell you about only one of your 16 great-great-grandparents. That leaves a huge number of unknowns.”

Genetic ancestry tests examine the sequence of molecules, called nucleotides, in a person’s dna. they focus on what scientists consider “junk” dna—portions of the human genome for which no biological function has been identified. An individual’s DNA sequence is compared to a database of samples to identify others with similar DNA sequences. The testing company then suggests that the customer’s ancestors lived in the geographic region and belonged to the ethnic group in which the customer’s dna sequence is most common.

However, Bolnick finds the tests tend to ignore the fact that many DNA sequences are found in many different human populations. For example, certain DNA sequences may be most common in Native Americans, but they also are found in Asians. As a result, some tests may incorrectly inform someone they have native american ancestry when their ancestors actually lived in Asia.

“Many companies try to link your DNA to racial and ethnic categories in ways that are problematic,” Bolnick says. “These categories are socially constructed, and they’re mostly based on cultural heritage and shared experiences. there’s no clear-cut connection between racial identity and your genetic makeup. Unfortunately, these tests incorrectly imply that there is, so they may encourage a return to old ways of thinking about race as purely biological, which it’s not.”

—Deborah Bolnick

So what questions can the tests answer?

“It depends on what you want to know,” Bolnick says. “if you want a specific question answered, like, ‘is there Native American ancestry on my mother’s side of the family?’ then a genetic ancestry test can probably tell you something about your direct maternal lineage. But the tests usually can’t tell you that you’re descended from someone like Genghis Khan with any real certainty. nor can they be positive that your ancestors lived in a particular region or held a specific ethnic identity. People move. Identities change over time.”

DNA ancestry testing has been especially popular among African Americans. Due to the transatlantic slave trade, many African Americans cannot easily trace their ancestry through surname research and other traditional means. DNA testing offers an unprecedented opportunity to find out more about their heritage.

The 2006 PBS documentary “African American Lives” tested the DNA of several prominent African Americans, including Whoopi Goldberg, Oprah Winfrey and Quincy Jones. Winfrey’s results suggested her most likely match was from the Kpelles tribe in Liberia. The documentary showed that genetic ancestry tests can have a profound impact on how the test-taker perceives his or her racial identity. However, an individual’s racial identity does not always match his or her genetic ancestry, warns Bolnick.

“What happens if the results don’t match how you’ve identified yourself your whole life? Do you accept them, question them, or get depressed?” Bolnick asks. “Many people are taking the tests to get answers about their identity and instead end up with an identity crisis. As a society, we need to think about the broader implications of the tests and whether they should be more important than your personal experiences.”

One issue that concerns Bolnick is the risk the tests pose for Native American tribes. No federally recognized Native American nation relies on DNA testing when determining tribal enrollment. Instead, membership usually requires documenting ancestral ties to a specific tribal member and providing evidence of community involvement. Bolnick worries the rise of genetic ancestry testing could undermine tribal sovereignty.

“For 150 years, Native American citizenship has been determined by legal criteria that support the tribes’ sovereignty as political entities,” Bolnick says. “DNA tests are starting to be used to challenge tribal decisions when someone doesn’t meet the tribe’s membership criteria. But why should tribes give up authority to a test that can’t reliably affiliate a test-taker with a specific tribe or ensure that tribal members are culturally connected and committed to the tribe’s future?”

Alumnus Creates Global Genealogy Map

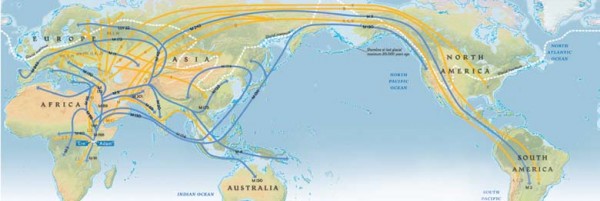

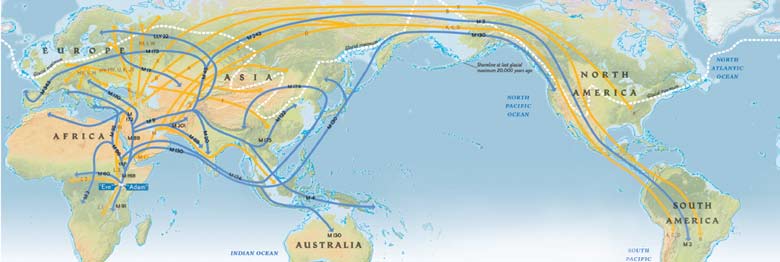

Though many questions remain about how we should interpret the clues revealed in our dna, scientists are rushing to expand the global database of genetic samples. One of the most ambitious collection efforts to date is the Genographic Project, started by national Geographic in 2005 and led by geneticist and Texas Ex, Spencer Wells (B.A. Biology, ’88). The project uses participants’ dna to map and trace migration patterns of humans who lived thousands of years ago. The five-year, $50 million effort aims to collect 100,000 dna samples from around the world.

“It’s been a lifelong dream of mine to answer some of the big questions like: where did we come from? How did we produce these patterns of diversity?” Wells says.

From the snow-covered Tibetan highlands to the burning windstorms of the Sahara Desert, Wells traverses the globe collecting samples from indigenous groups in the world’s most remote locations.

“When humans first ventured out of Africa some 60,000 years ago, they left genetic footprints that are still visible today,” Wells says. “By mapping these ancient ancestral clans called haplogroups, we create an atlas of when and where ancient humans moved around the world.”

As of 2007, the project has collected more than 20,000 samples from roughly 100 indigenous groups across five continents. An additional 200,000 people, mostly from North America, have submitted samples for testing. The project has even caught the attention of Bono, lead singer for the Irish rockgroup U2, who had his DNA tested for Vanity Fair’s July 2007 Africa issue.

For about $100, the Genographic Project will test your DNA and reveal a few aspects of your deep ancestry, the ancient migratory paths of one of your lineages. however, Wells cautions that this is not an individual genealogy study. You won’t receive a breakdown of your genetic background by ethnicity or race or geographic origin.

“We are extremely careful not to overstate results. I also want to emphasize that interpretations may change as we continue to collect data. We just don’t know enough to assign people to an ancient tribal group,” Wells says. “Telling someone, ‘You are 10 percent such-and-such, and 90 percent such-and-such, and so on’ is worrying to me. We’re talking about genetic lineages, not racial classifications.”

So why are we as Americans so fascinated by our ancestry?

Both Bolnick and wells believe it’s because of our history as a nation of immigrants.

“A lot of people came here running away from something, or they came against their will. it’s very human to want to find connections, to feel like we belong to a place and a people,” Wells says. “Your DNA is just one of many tools that you can use to confirm what you know, or find out something new about your ancient heritage,” Bolnick adds. “It’s fascinating that our cells contain information about our history, but we shouldn’t privilege genetic data over our personal, cultural experiences.”

First Person: Out of Africa

By Juliet E.K. Walker

Professor of History

African-American Identity is based on a shared history of slavery, racial oppression, discrimination and inequalities in all areas of American life. My great-great-grandfather Free Frank was born a slave in 1777. His mother was African born, his father was the slave-holder. Other ancestors also were slaves.

Regardless of what a DNA test might reveal, I would still consider myself African American. What else could I consider myself as a result of my family heritage of slavery and as a result of my own life experiences as an African-American woman dealing with racism?

The United States’ African-American population always has been a mixed-race population with their African heritage dominating and providing the basis for their identity as African Americans. Some scholars have estimated that as much as 80 percent of the descendants of the 4.5 million blacks in the United States in 1860 had some European ancestry, in addition to those with Native American ancestry.

Race is a societal construct and DNA tests have contributed little to change African American’s sense of racial, cultural and American historical identity. For the most part DNA, presently, is important to blacks only as a means to identify their specific African ethnic heritage.

For me, DNA tests, regardless of results, would not, could not, cannot, will not change my sense of identity as an African American.

Juliet E. K. Walker is a history professor and director of the Center for Black Business History, Entrepreneurship and Technology at the university. She is the author of “Free Frank: A Black Pioneer on the Antebellum Frontier” and “The History of Black Business in America: Capitalism, Race, Entrepreneurship.”