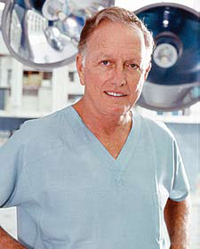

Today, as Cooley, a 1941 zoology graduate from The University of Texas at Austin, walks through the state-of-the-art operating suites at the Texas Heart Institute in Houston, he can recall a time when surgeons propped open operating room windows to allow in the “sterile” breezes.

He has seen it all.

As a doctor and an innovator, Cooley has long modeled a singular dedication to the welfare of his patients: when available medical science failed them, he invented new techniques and instruments.

In this dedication, he followed the footsteps of his famous mentor, Dr. Alfred Blalock, namesake of the operating room procedure to correct congenital heart defects in infants. As a young intern at Johns Hopkins Hospital, Cooley assisted Blalock in that first surgery in 1944.

“Dr. Blalock had been investigating hypertension in pulmonary circulation and thought it would be an interesting thing to achieve,” Cooley remembers. In what was considered a high-risk operation, Blalock used his experimental technique to remove oxygen from the baby’s lungs.

“Most thought it was impossible because it involved putting a very sick baby under general anesthesia,” says Cooley. “But the outcome was so spectacular that it was a strong impetus to develop refinements to the practice.”

Cooley found his calling in the operating room that day. He went on to pioneer innovations in surgery, including a heart-lung bypass machine and techniques to correct congenital cardiac anomalies, refine artificial heart valves and improve coronary bypass surgery.

Due to his innovations in the 1960s, the mortality rate for valve transplant patients fell from 70 to eight percent. He was the first surgeon to successfully remove pulmonary embolisms (sudden blockages in lung arteries, usually caused by a blood clot), with a technique that squeezed the lungs flat to remove inaccessible clots during temporary cardiopulmonary bypass.

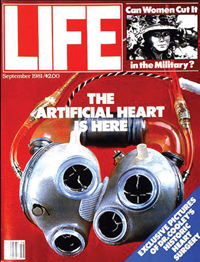

Featured on the cover of LIFE magazine in 1968 and again in 1981, Cooley is no stranger to the limelight. But like anyone in the vanguard of an emerging field, he also has seen his share of controversy.

Cooley says that, through it all, his guiding principle has been to keep an open mind. Advances occur only because someone takes a leap, reaches beyond what is known to explore the possible.

“Physicians must use their imaginations to develop new techniques, always with the welfare of their patients as their number one priority,” he says.

During his more than 60 years on the job, Cooley has accumulated more honors than perhaps any other physician in America. Among his more than 120 awards are the Grand Hamdan International Award for Medical Science, National Medal of Technology, Medal of Freedom, Theodore Roosevelt Award, and Rene Leriche Prize.

But for Cooley, his greatest achievements are founding the Texas Heart Institute and the Cardiovascular Surgical Foundation, where the octogenarian still guides the next generation of surgeons who continue his pioneering work—developing devices to support and replace the human heart during surgery.

Cooley credits his good health and natural stamina for his long and extremely prolific career. And his agility and speed in the operating room, he believes, stemmed from the determination and focus he developed as a varsity basketball player at the university.

It wasn’t until last year that he finally laid down his scalpel, arbitrarily selecting his 87th birthday as the end of his surgical career. For someone who conducted surgery nearly every day for six decades, quitting cold turkey was difficult. “I’ve had withdrawal symptoms,” he laughs.

But he’s a long way from retiring altogether. He is a frequent visitor in the operating room, and makes rounds with residents and students to see patients and give diagnostic and treatment advice.

Aside from a greatly improved landscape for heart surgery, Cooley’s legacy includes a family full of medical professionals. He and his wife, Louise, have five daughters, among them an opthamologist, a medical illustrator, a public health and nursing professional, and a wife of a cardiovascular surgeon. Two of his grandchildren are in medical school, and he expects others will follow. It is in the arteries, so to speak!

As his grandchildren prepare to follow in his footsteps, Cooley believes the digital age holds much promise for the next wave of medical advances.

“Major challenges today include finding a method of control or cure for malignant disease and further improvements in diagnostics,” he says. “Computers will focus physicians’ persistent curiosity and fuel the innovation it will take to overcome them.”