500,000-year-old fossil points to modern health concerns

As Turkish workers cut into a block of travertine stone destined for the international tile market, they uncovered a 500,000-year-old fossil, which anthropologist John Kappelman is using to expand scientists’ understanding of tuberculosis–and how the infectious disease may affect people who migrate.

“Tuberculosis has re-emerged as a global killer during the past two decades,” Kappelman says. “This ancient fossil reveals a case history similar to that of many modern patients since the disease was probably exacerbated by a vitamin D deficiency, which resulted after the species migrated north from the tropics into the temperate climates of Eurasia.”

— John Kappelman

Although most researchers believed tuberculosis emerged only several thousand years ago, Kappelman revealed the most ancient evidence of the disease in the fossil workers unearthed in Pamukkale in western Turkey.

The physical anthropologist’s discovery of Homo erectus, a new specimen of the human species, suggests support for the theory that dark-skinned people who migrate northward from low, tropical latitudes produce less vitamin D, which can adversely affect the immune system, as well as the skeleton.

Kappelman is part of an international team of researchers from the United States, Turkey and Germany who published their findings in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology last year. The Leakey Foundation and the Scientific and Technical Research Council of Turkey funded the research.

Prior to this discovery, which helps scientists fill a temporal and geographical gap in human evolution, the oldest evidence of tuberculosis in humans was found in mummies from Egypt and Peru that date to several thousand years ago. Paleontologists spent decades prospecting in Turkey for remains of Homo erectus, widely believed to be the first human species to migrate out of Africa. After moving north, the species had to adapt to increasingly seasonal climates.

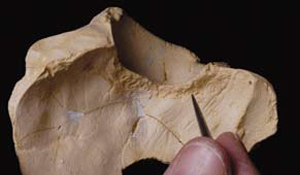

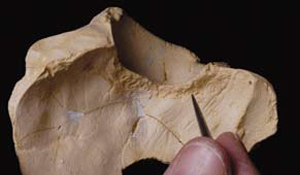

The researchers identified this specimen of Homo erectus as a young male, based on aspects of the cranial suture closure, sinus formation and the size of the ridges of the brow. They also found a series of small lesions etched into the bone of the cranium whose shape and location are characteristic of the Leptomeningitis tuberculosa, a form of tuberculosis that attacks the meninges of the brain.

Vitamin D: Protecting People Who Migrate

After reviewing the medical literature on the disease that has re-emerged as a global killer, the researchers found some groups of people demonstrate a higher than average rate of infection, including Gujarati Indians who live in London, and Senegalese conscripts who served with the French army during World War I.

The research team identified two shared characteristics in the communities: a path of migration from low, tropical latitudes to northern temperate regions, and darker skin color. People with dark skin produce less vitamin D because the skin pigment melanin blocks ultraviolet light. And, when they live in areas with lower ultraviolet radiation such as Europe, their immune systems can be compromised.

It is likely that Homo erectus had dark skin because it evolved in the tropics, Kappelman explains. After the species moved north, it had to adapt to more seasonal climates. The researchers hypothesize the young male’s body produced less vitamin D and this deficiency weakened his immune system, opening the door to tuberculosis.

“Skin color represents one of biology’s most elegant adaptations,” Kappelman says. “The production of vitamin D in the skin serves as one of the body’s first lines of defense against a whole host of infections and diseases. Vitamin D deficiencies are implicated in hypertension, multiple sclerosis, cardiovascular disease and cancer.”

Before the invention of antibiotics, doctors typically treated tuberculosis by sending patients to sanatoria where they were prescribed plenty of sunshine and fresh air.

“No one knew why sunshine was integral to the treatment, but it worked,” Kappelman says. “Recent research suggests the flush of ultraviolet radiation jump-started the patients’ immune systems by increasing the production of vitamin D, which helped to cure the disease.”

‘Beautiful’ Bones: Lucy the Famous Fossil

After years of storage in a vault in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, Lucy the famous fossil, the oldest and most complete adult skeleton of any erect-walking human ancestor, traveled to Texas in 2007. The Houston Museum of Natural Science featured the 3.2 million-year-old hominid, whom Ethiopians call “Dinkenesh” (“You are beautiful”), at the exhibition, “Lucy’s Legacy: The Hidden Treasures of Ethiopia.”

John Kappelman leads a scientific team that has requested permission to conduct a high-resolution CT (computed tomography) scan of Lucy, whose remains include portions of her skeleton.

“By examining the internal architecture of Lucy’s bones, researchers can study how her skeleton supported her movement and posture, which can be compared with modern humans and chimpanzees,” the physical anthropologist explains.

Although Lucy is quite small (about 1 meter in height), her contribution to science has been large. She represents a new species of human ancestor, known as Australopithecus afarensis, or “southern ape of Afar,” in reference to where the bones were found. Prior to the 1974 discovery of Lucy, theories of evolution suggested human-like intelligence evolved before upright posture. But, the existence of Australopithecus refutes this theory since Lucy’s brain case is not significantly larger than a modern chimpanzee, yet she certainly walked on two legs.

With 40 percent of her skeleton preserved, Lucy the famous fossil is the oldest and most complete skeleton of any adult erect-walking human ancestor. Anthropologist John Kappelman has requested permission to conduct a high-resolution scan of the rare and important scientific discovery.

See www.eLucy.org for more information.