Anthropologist separates fact from fiction

From the moment Indiana Jones performed his first death-defying stunt on the big screen in 1981, moviegoers and archaeologists alike have been enthralled by the globetrotting, whip-cracking action hero.

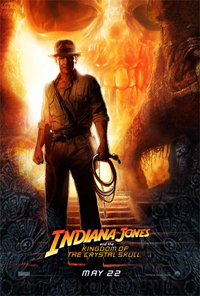

From recovering ancient biblical artifacts to rescuing damsels-in-distress, the fictional archaeologist stops at nothing to save the world from political imbalance—even if he has to break every code of ethics in archaeology along the way. Jones’ recent adventures in “Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull,” spurred an onslaught of mixed reviews, especially among expert archaeologists.

With the release of each Indiana Jones film, enrollment in archaeology courses surges, giving professors the opportunity to separate facts from the myths about archaeology.

Fred Valdez, associate anthropology professor at the University of Texas at Austin, says archaeology is not about traveling to exotic countries and raiding tombs. It is large groups of students and researchers painstakingly shoveling through dirt to recover ancient objects that can reveal how our ancestors once lived.

But at the end of a long day, despite the head-to-toe dirt, bug bites and aching muscles, most researchers return to camp smiling and satisfied with the work they have accomplished.

“The digs can be slow and meticulous,” Valdez says. “But at the same time, you really don’t know what the next scrape of ground will reveal and that’s what’s exciting.”

Valdez says despite director Steven Spielberg’s far-fetched depiction of archaeology, Indiana Jones stimulates much needed interest in a sometimes overlooked field of science.

“The Indiana Jones series has created a romance that draws people to archaeology,” Valdez says. “Many people out, they are inspired to enroll in a class or participate in an excavation.”

From being called a “glorified looter” to “destroyer of the ancient world,” Jones has been criticized for his haphazard approach to archaeology. In addition to Jones’ myriad of misdeeds, he fails to thoroughly document and record his findings, which, according to Valdez, is the most important part of archaeological excavations.

“Archaeology can be a destructive process,” Valdez says. “We take apart things we study. But when Indiana Jones recovers artifacts, he isn’t exactly preserving or documenting his findings.”

Many experts suggest the hollywood portrayal of archaeology leads people to believe the sole purpose of excavations is to recover precious gems or priceless, mythical artifacts. Valdez explains the field isn’t just about the objects they dig up. it is about uncovering the mysteries of our past.

As an archaeology professor, Valdez shares some similarities with Jones, minus the whip and the dusty fedora. Both conduct field research in exotic lands. amid spider monkeys, snakes and tropical birds, Valdez has been conducting field work in remote rainforests for more than 30 years. As the director of the Programme for Belize archaeological Project, a summer and spring field school, he investigates ancient Maya civilization.

Underneath a dense canopy of rainforest, Valdez and his team of students and researchers from across the globe have investigated more than 60 Maya sites including pyramids, small house mounds and tombs that date from 1000 B.C. to 1400 A.D. Digging for hours to unearth pottery fragments and architectural remains may not entice the average thrill seeker. But to archaeologists, there is nothing more exciting than finding remnants from the ancient world.

“Once the students fully understand the meaning of archaeology, the ideas of action and adventure quickly slip away, replaced with the excitement of being the first to hold an object that has not been touched in 2,000 years,” Valdez says.