Language, religion and culture are keys to understanding diverse region

While more than one million Arabs live in the United States, the majority live in five states—California, New York, Michigan, Florida, and New Jersey—so Arabic language and culture remain quite foreign for many Americans.

Kristen Brustad, an Arabic studies associate professor at The University of Texas at Austin, recalls a lecture during the mid-1990s. She asked the College of William and Mary audience of roughly 75 to raise their hands if they knew anything about the Middle East, where the majority of Arabs live. Only two did. Then she asked who knew something about women in the Middle East, and nearly half raised their hands.

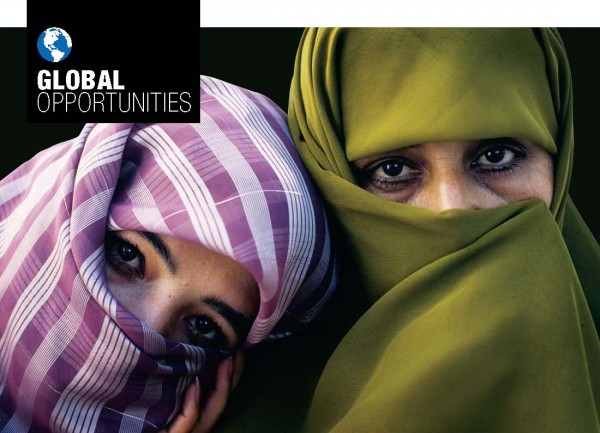

That response, Brustad says, is indicative of the assumptions and myths that many Westerners rely on. Cultural, religious and linguistic differences often serve as barriers, preventing an accurate picture of the Arab world from emerging. Even the phrase “Arab world,” which refers to people who speak Arabic as their first language, is often miused, mistakenly viewed as synonymous with the Middle East or the Muslim world.

Once relegated to the periphery of American life, mostly in stereotypical film and television depictions, Arabi culture was thrust into the spotlight after Sept. 11, 2001. During the following months, enrollment in Arabic language classes skyrocketed, the Qur’an became a bestseller, and Oprah Winfrey dedicated an episode of her talk show to understanding Islam, the predominant religion in most Arab-speaking countries.

The war in Iraq increased interest, as soldiers, government officials, journalists and private contractors, many with limited knowledge of the language or culture, adjusted to life in a foreign land.

The first step toward true understanding of Arab culture is gaining knowledge of Arabic language, Brustad says. Both ancient texts and modern-day marketplace negotiations hold valuable clues about the Arab world.

Although the U.S. government has identified Arabic as a language critical to national security, few Americans are proficient. Interest in the language has soared in recent years, but college enrollment is far below more popular languages. In 2002, 10,000 students enrolled in college-level Arabic courses. The Modern Language Association’s 2006 figures show Arabic college enrollment at about 24,000, compared to more than 700,000 in Spanish.

Sheila Weaver, a senior in the university’s Arabic Flagship Program (see sidebar), encountered the language while working at an Arab restaurant. She began Arabic classes, and stayed at work after her shift to watch Arabic television and practice speaking with her coworkers. She is devoted to the language, planning to live in the Middle East after graduation and, eventually, teach Arabic.

During the summer, Weaver experienced her first taste of life abroad, studying Arabic in Damascus, Syria. Unaccustomed to foreign visitors from Western countries, residents were surprised to learn Weaver was American. But, her knowledge of the language helped smooth the transition to a culture vastly different from her own.