“Understanding the language, even a little bit, opened so many doors for me,” Weaver says. “Arabs have many different customs. They value politeness and manners. I would have been lost and could have offended people if I didn’t have the language to help recognize conversational nuances.”

For instance, in the United States a person playfully trying to fool someone might jokingly be called a liar. But in Syria, to be called a liar under any context is extremely insulting. “You should say ‘You’re a joker’ or ‘You’re a kidder’ instead,” Weaver explains. Often, it is the simple, sometimes mundane, moments such as telling a joke, ordering dinner or hailing a taxi that provide the most meaningful insight into a culture.

Mealtime rituals reveal Arabs’ pride in hospitality. If a guest eats all the food on his or her plate, the host will continue to serve additional portions, no matter how much the guest may protest. The host only will stop serving after the guest proclaims, “Al-hamdu lillah,” (“Thank God”) signifying satisfaction with the meal.

A Focus on Faith

The word Allah (“God”) is used in many Arabic expressions, reflecting God’s place in everyday Arab life. When discussing future plans, Arabic speakers follow a statement with In shaa’ allah (literally “If God wills,” or “hopefully”).

“Westerners taught not to speak God’s name in vain are sometimes shocked to hear the word ‘Allah’ spoken so often in regular speech,” Brustad says. “But for Arabic speakers, it is reverential.”

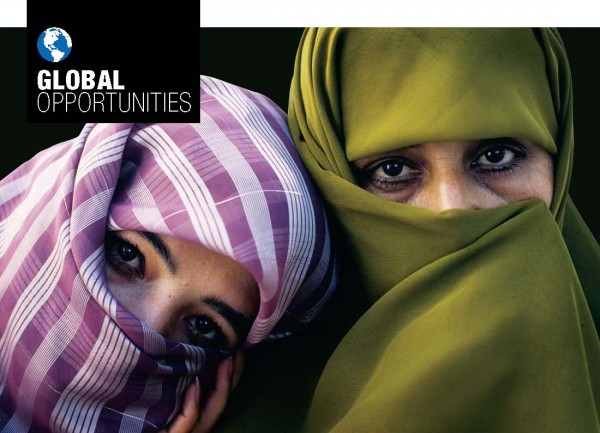

Misconceptions about religion in the Arab world are common, says Martha Newman, chair of the Department of Religious Studies. Stereotypical notions of religious homogeneity, veiled women and violent jihads distort reality.

Most Arabs are Muslim (followers of Islam), but the majority of the world’s Muslims live in South Asia, not the Middle East. Middle Eastern countries such as Lebanon and Syria are religiously diverse and are home to Sunni and Shi’ite Muslims, Christians and Roman Catholics, as well as Druze and Alawite communities, which are offshoots of Islam. Lebanon has a large Christian population that includes Maronite and Melkite Catholics, and Greek and Armenian Orthodox communities. The country recognizes 18 different religions. Perhaps as much as one tenth of Egyptians are Coptic Christians, a denomination founded in the early orthodox Christian church.

“If you think about the Arab world monolithically, you lose the complexities of the religious, cultural and ethnic landscape of the region,” Newman says. “What people call ‘religious conflicts’ are complex. They’re about politics, natural resources and power, as well.”

Despite the Arab world’s enormous religious diversity, the region’s linguistic history connects it most intimately to Islam.