Professor uses prize money to explore ancient civilization

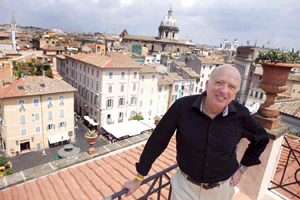

Staring down the challenge of a research project that spans 12 centuries of Roman civilization, Karl Galinsky’s expression is that of a confident gladiator.

And who better to lead the charge than Galinsky, who admits he’s “not afraid to rattle some cages and have some fun” while embarking on his latest adventure.

Galinsky, the Floyd A. Cailloux Centennial Professor of Classics and Distinguished Teaching Professor at The University of Texas at Austin, has won the 2009 Max Planck Research Award for International Cooperation. The Max Planck Society, in collaboration with the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, awards the approximately $1 million, (750,000 euro) prize in humanities to each of two scholars selected every four years.

He will use the money to support an interdisciplinary group of doctoral candidates and researchers investigating the role of cultural memory in Roman civilization. In addition, the funds will allow him to work on the project from Ruhr-U-University in Bochum, Germany where his research will interact with other projects on memory including the history of religions and neuroscience. Work begins this fall.

Nominations for the award are made by German universities and screened by a joint selection committee from The Max Planck Society, an independent, non-profit organization that promotes research in the natural sciences, life sciences, social sciences and the humanities; and The Alexander von Humbolt Foundation, which supports academic exchange between scientist and scholars from Germany and abroad.

Dr. Gerhard Ertl, the 2007 Nobel Prize winner in Chemistry, chaired this year’s committee, which credited Galinsky with “building bridges to current themes such as disenchantment with politics and multiculturalism.”

Galinsky feels his generalist’s approach and proven track record may have given him a competitive edge during the selection process.

“I’m not knocking people who reside in one area of specialization,” says Galinsky. “It all depends on the quality of the work, but what I enjoy and what helped me win this award is that I’ve covered a lot of ground crossing the time spectrum of Roman civilization.”

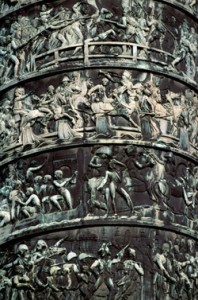

He believes themes of Roman civilization should be approached from multiple perspectives. For him, it’s important to study Rome’s literature, historiography, religion, architecture, arts, social history, how it’s remembered, and how those perspectives all intersect. He aims to study these on a more comprehensive and integrated basis than ever before.

Galinsky will explore connections between Roman antiquity and its perception in modern culture: how cultural memory works in Rome, who shapes ideas, who is in control and what is conveniently forgotten. In his research, he has learned that cultural memories sometime depend on who is remembering what and why.

“While Ancient Rome was considered by researchers to be a written culture, much of the information we have today was simply handed down by word of mouth,” says Galinsky. “Very few people wrote history, and those who did were typically elites.” This can prove particularly challenging as Galinsky tries to reconstruct the cultural memories of the common people—technical evidence supporting their voices is rare if it exists at all.

“Very few people were literate, so memory and the transmission of memory have a big role of interest,” he adds.

Cultural memory over time has become a catch phrase that means different things to different people, but Galinsky defines it as the memories that groups of people have specifically about their own traditions and cultures, which help shape national identity.

“To the Romans, history is so important,” says Galinsky. “It’s what they go by. Whenever they have any issue they say, ‘How was that done by our ancestors? How was that resolved?’ The past continues to be held up as a model for the present.

“Rome is a memory culture and that’s the bottom line,” he adds. “They thrive on it—it’s an historical phenomenon. It’s constant in everything they do and everything has to be anchored in the past.”

Galinsky’s research delves into who shapes that anchor and what other anchors have been cast overboard. He takes into account that we all see past events through the prism of present times. He gives the example of our constant reassessments of American presidents such as Andrew Jackson, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Abraham Lincoln. What do they really mean to us and how do we remember them differently than others?

If navigating 12 centuries of Ancient Rome, from its early days in the 8th century B.C. to the fall of the Western Empire in 5th century A.D, wasn’t challenging enough, Galinsky must also face the ever-constant comparisons between the United States and Rome.

“America is the modern Rome,” says Galinsky. “There is life for Rome after 12 centuries because the whole interaction between Rome and the United States is fascinating. You can take a look at the parallels in our constitution, politics, architecture, sports venues and pop culture.”

The history of the Roman Republic, in particular, may have resonated with our founding fathers. They faced many of the same struggles with authority. As with the early Romans, those struggles eventually led to the creation of checks and balances and limited terms of office. The U.S. Constitution’s guiding principles are modeled heavily on the Romans’. Surprisingly, the Roman model was not based on a written constitution, but on memory.

Also like the United States, the city-state of Rome was culturally, socially, racially and ethnically integrated. Genetically, being Roman, just like being American, meant different things at different times. If you compared the collective DNA of the Romans in 200 B.C. to 200 A.D., it would be very different.

“You don’t have the idea of a Roman master race,” says Galinsky. “In Rome, domestic slavery, which had nothing to do with race or skin pigmentation, usually lasted 10 years or less and eventually led to freedom. But here’s the thing, their children automatically gained Roman citizenship.”

While Galinsky takes note of Rome’s military prowess and strength, he credits its “soft powers” such as the ideas of liberty, religious tolerance, economic opportunity and social mobility for its long-term success. The rule of Augustus (27 B.C. to 14 A.D.) initiated an era of relative peace in the Mediterranean, which spanned two centuries, known as the Pax Romana or Roman peace.

“With all the conquest, it works because the people see an opportunity to be in a system with more economic opportunity and social mobility, similar to the United States today,” says Galinsky.

“Looking at the entire Roman Empire across the Mediterranean,” concludes Galinsky, “if everyone had tried to get out of there, forget about it, the size of the army—some 300,000— would never have been enough to keep them in for this long.”

Learn more about Galinsky’s research project, including conferences and resources, from the Memoria Romana website.