Museum exhibit highlights Galveston as America’s Forgotten Gateway

While riding a ferry to America’s most famous port of entry, Ellis Island, with a group of Texas high school students on a Jewish heritage tour, Suzanne Seriff began to wonder about the lesser-known gateways to America.

Her curiosity about Galveston’s largely forgotten history as a major immigration port was sparked when a student asked, “Why did we have to go all the way to New York to find out about our ancestry? My family came through Galveston.”

“That was when a light bulb flashed and I thought, nobody really knows about Galveston,” says Seriff, a senior lecturer of anthropology at The University of Texas at Austin. “That’s why we call it a forgotten gateway. What many people don’t know is that during the late 1800s, it was one of the top ports of entry in the country.”

After that conversation, which came just six months after the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks, Seriff felt the need to create a venue geared toward fostering tolerance and a sense of empathy for immigrants in the United States. During that time, children were reflecting their parents’ fears, Seriff says. And that fear was affecting how people saw strangers among us, especially new immigrants.

When she returned to Texas, she submitted a proposal to the Bob Bullock Texas State History Museum. Seven years later, in February 2009, the “Forgotten Gateway: Coming to America through Galveston Island” traveling exhibit premiered in the museum’s Albert and Ethel Herzstein Hall of Special Exhibitions.

The exhibit closed in October, but will soon travel around the nation to other institutions, including Moody Gardens in Galveston and the Ellis Island Immigration Museum.

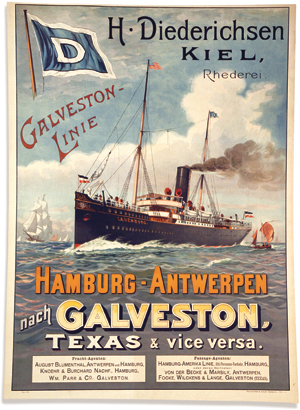

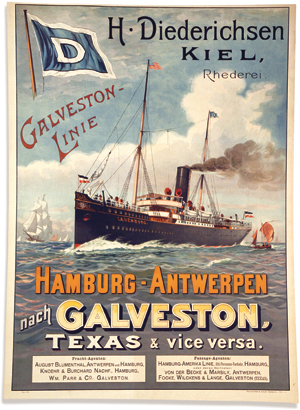

Created by a team of anthropologists, humanities scholars, historians, educators and designers, the exhibition tells the story of Galveston’s legacy as one of America’s top 10 transoceanic ports of entry from 1845 to 1924. Its four rooms have different themes: “Difficult Journeys,” “Immigration as Big Business,” “Our Nation’s Rising Xenophobia” and “The Changing Immigration Laws after World War I.”

Each historical account is presented along with contemporary stories told by immigrants and descendants of immigrants who have confronted the same challenges — from dangers along the way to conflicts upon arrival, including discrimination and fights over land rights.

Extending its stories beyond the realm of history, the exhibit uses the lessons of prejudice, bigotry and inhumanity to teach empathy and understanding of others, says Seriff, who is serving as the guest curator for the exhibit.

“Our goal is to increase tolerance about people from all cultures,” she says. “And we want to help our visitors see that current issues we see as problems today relate to many immigration issues throughout our nation’s history.”

The untold stories of Galveston’s role as a major thoroughfare for immigrants are revealed through hundreds of pictures, illustrations, videos, oral narratives and more than 140 original documents and artifacts, such as a handmade quilt crafted by an African slave, personal journal entries and letters.

The exhibit also offers an in-depth look at the Galveston Movement, an organized immigration plan formed by Jews who escaped violent anti-Jewish attacks in Russia and Eastern Europe by coming to the United States through Galveston.

Robert Abzug, director of the university’s Schusterman Center for Jewish Studies and the Oliver H. Radkey Regents Professor of History and American Studies, said he enjoys visiting the exhibit to see Galveston’s storied history come to life through the myriad interactive displays.

“This exhibit brings together a wonderful combination of well-researched displays and interactive tools that make Galveston’s history as a port city both a vivid story in its own right and a piece of the larger account of American immigration,” says Abzug.

Providing an opportunity for discussion, each room features interactive kiosks, where visitors can share their own stories or join the conversation about particular issues by leaving answers to specific questions on Post-its on the wall.

“Our visitors are an important part of the exhibit,” Seriff says. “We try to create an opportunity for multiple voices at all times to contribute to the story. Not just the authority of my voice, but the authority of various perspectives from the past and present.”

Supported by The National Endowment for the Humanities and a host of other donors and organizations, the exhibit has facilitated several community outreach initiatives geared toward engaging different immigrant communities. The special programs include storytelling sessions, youth theater workshops and discussion groups.

To tell the story of Galveston’s overlooked history to a broader audience, the museum will produce a smaller-scale version of the 6,500-square-foot exhibit to transport to immigration centers, schools, libraries and community centers around Texas and the country. The portable exhibit will feature replicas of artifacts, digital media and an array of interactive attractions, allowing visitors to leave comments and share their own experiences.