When Sidney Monas was taken in as a German prisoner of war during World War II, he remembers being huddled in boxcars — cold, hungry and dehydrated — as he was transported all over the German railroad network to Nuremberg.

During the 10-day long train ride, Monas was exposed to strafing attacks from U.S. aircrafts. Air Force pilots had no way of knowing the train they were strafing carried American prisoners of war. Starving, cold and under attack, Monas and his fellow passengers were actually glad to arrive in prison camp.

To keep a low profile, Monas decided not to let his captors know he spoke German. But when another prisoner came down with blood poisoning and a raging fever, Monas was the only person in the prison block who could call to the guards for help in German. The wounded “kriegie,” as the Germans called the prisoners (short for kriegsgefangener or POW) received some medical attention, but Monas never saw him again.

The Germans then decided to make better use of Monas, by making him an interpreter between guards and “kriegies.” One particular incident that continues to stand out in Monas’ memory occurred when the camp’s political officer objected and refused to approve him as a trustee, declaring he was a Jew.

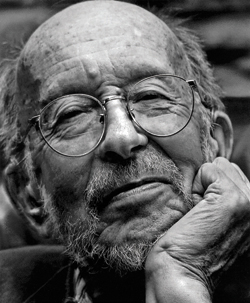

“For the only time in my life, I had to deny my identity to save my life,” says Monas, now a professor emeritus of history at The University of Texas at Austin. “I had bad dreams about that denial for many years to come.”

Monas, 84, candidly details his experiences as an American Jew in German captivity for five months in his memoir “My Life and Not so Hard Times,” published in “Burnt Orange Brittania,” (I.B. Tauris, 2006) a collection of autobiographical essays by top university historians and scholars of the British experience.

“It was a bad experience at the time, but when I think back on it, perhaps I was very fortunate,” he says. “Being a prisoner, I had a glimpse at what a hard time might be like, but I was lucky to get out of it in five months. Looking back on my life, I don’t think I had very hard times.”

During his many idle hours as a prisoner of war, he decided that when he got back to college — his freshmen year at Princeton had been cut short when the Army sent him to Europe — he would study history to learn about the great movements of mankind and their unfortunate tendency to turn to war.

Monas graduated magna cum laude from Princeton in 1948 and earned a Ph.D. in history from Harvard in 1955. After teaching briefly at Amherst and Smith Colleges and the University of Rochester, Monas joined The University of Texas at Austin in 1969, enticed by the opportunity to develop a British Studies seminar. Until his recent retirement, he actively and happily collaborated with Wm. Roger Louis, professor of history and director of the British Studies program, in running the well-known seminar.

Since 1975, the seminar, open to faculty members, students and scholars, has met every Friday during the fall and spring to examine topics in literature, history and world affairs.

During his tenure at the university, he taught popular courses in the history and English departments, such as “Shakespeare and Tolstoy.” Recognized for 40 years of dedicated and outstanding service to the college, Monas is among the 2009 Pro Bene Meritis recipients.

Monas brought international fame to the university with his translation of “Crime and Punishment” (Signet, 1968). And for six years, he edited the Slavic Review, the journal of the American Association for the Advancement of Slavic Studies.

Whether he’s traveling across the globe, as he regularly does, or relaxing at home, he always makes sure to keep a copy of James Joyce’s “Finnegans Wake” on hand.

“‘Finnegans Wake’ is the ultimate comic novel, looking at earth shaking struggles and saying ‘how small it’s all!’ Every time something gets me down,” Monas says. “I pick up my copy of the Wake, open it at random and let the laughter overtake me.”