Scholars reveal the stories behind some of the world’s most inspired love letters

A little over a year ago, Janine Barchas witnessed a marriage proposal in a crowded hotel ballroom. The young man left nothing to chance, relying on the words of a Jane Austen love letter—almost crafting his entire proposal from it.

“The young lady said ‘yes,’ a roar of applause followed, and all of us had the good manners not to bring up plagiarism,” jokes Barchas, an associate professor in the English Department and director of the English Honors Program. “Whatever Austen’s appeal, she apparently remains a good source to turn to in matters of the heart.”

Whether it’s the first love letter you received—most likely an oversized masterpiece of red construction paper that smelled of Elmer’s glue—or a slightly more sophisticated offering of poetry you keep tucked away in that special shoebox of treasures, there is something resounding about how a love letter lives on—in many instances long beyond the romance itself. But what makes a love letter extraordinary?

University of Texas at Austin professors share their thoughts on some of the greatest love letters of all time. In the wedding proposal Barchas saw, the young man quoted the love letters of Austen’s character Captain Wentworth from her classic romance “Persuasion.” After the novel’s heroine Anne Elliot refuses the captain’s marriage proposal, she suffers eight years of agony without him, relying only on snippets of news about him in navy lists and newspapers during his time at sea. After their epic separation, Captain Wentworth places a secret love letter for Anne re-declaring his love.

“Wentworth’s letter is passionately worded and exquisitely expressed, a model for us all to emulate,” says Barchas, who is working on a book about Austen. She credits its restraint as one of the primary reasons it is so breathtaking.

“I feel that if the captain had been able to e-mail, text or tweet numerous messages to Anne from the Mediterranean coast, even words as fine as these might have had less of an impact,” says Barchas. “Jane Austen’s writing, in general, works like this, too. Austen’s prose is powerful for its economy—for what she does not say, as much as for what she openly declares. Wentworth’s letter is emotionally explosive precisely because it is written in the context of social restraint and years of self-denial.

“The appeal of Regency rules and decorum may, in fact, be why Austen is so popular with students, and why we cannot seem to offer enough English classes about her novels to meet demand,” Barchas says of the author of “Sense and Sensibility,” “Pride and Prejudice” and “Emma,” among other works.

Austen published her work during the British Regency (1811-1820), a period known for its high standards of etiquette.

“Perhaps in a modern world with countless personal freedoms, young people yearn for a time when messages (a mere gesture, nod or glance) and their meanings were clearer, because there were fewer of them and so were measured and weighed more carefully.”

Ironically this great writer of romance never married and was engaged once for only 24 hours.

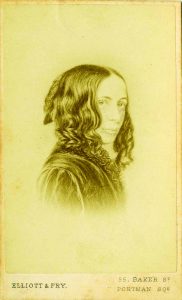

Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning are entirely a different story. You could say it was love at first write. For Carol MacKay, University Distinguished Teaching Professor in the Department of English, the love letters between the Brownings during their courtship offer the most poignant and powerful examples of amour.

“They wrote so many and such long letters over the course of a year and a half—555 between January 1845 and September 12, 1846, when they eloped,” says MacKay. “I do think that bits of their very first exchange of letters (before they had even met face to face) are fairly telling of the love that was to grow between them.”

MacKay explains that the London postal service was extremely efficient, usually making three deliveries per day and allowing the young lovers to write so frequently.

“Of course, this is all pre-Internet and pre-telephone, and in the case of the Brownings it was crucial to their courtship— although in that same 20-month period Robert did make 91 personal visits,” MacKay says of a period in which Elizabeth was bedridden. “But even for non-love-inspired correspondence, Victorian letter-writing was amazingly prolific. For any of the writers I study, there are somewhere between three and nine volumes of their published correspondence, and there are even more letters that didn’t get published or didn’t get saved.”

Elizabeth’s “Sonnets from the Portuguese” (“Portuguese” being a pet name given to her by Robert) contains her most famous poem and perhaps the most frequently quoted love letter of all time, number 43, that begins “How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.”

Like most good love stories, there are obstacles the couple must face. Elizabeth’s father disinherits her upon her marriage to Robert as he does each of his children who marry. The couple eventually ran away to Italy to elope and despite a lifetime of health issues, Elizabeth sees a tremendous improvement to her health, and at the age of 43 gave birth to a son. The writers fittingly name him Pen.

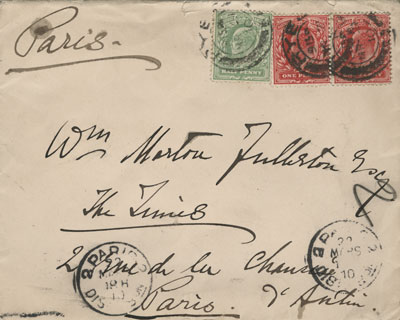

But not all love letters lead to such happy endings. Some are inspired by a love unrequited or unmatched. Such is the case with Edith Wharton, author of “The Age of Innocence” and “The House of Mirth.” Her letters written to younger lover Morton Fullerton are housed in the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas.

“In addition to these letters being beautifully written, they are quite poignant because even as Wharton expresses her love for Fullerton—and her gratitude to him for uncovering a passion in her that she never knew she possessed—she appears to recognize that he means more in her life than she ever will in his, and that she will eventually lose him,” says Phillip Barrish, associate professor in the Department of English.

“Her characteristic public pose was one of impressive dignity and a sort of strict propriety. In these letters she reveals a far more vulnerable side.” A love letter may reveal a softer, more vulnerable side of its author—often very different from one’s public persona—particularly if the author is, say, the President of the United States. Such is the case of Woodrow Wilson. Notably a reserved man in public, he signed a letter to Edith Bolling Galt, who later became his second wife and first lady, “Tiger.”

“Who we love reveals a great deal about ourselves,” says H.W. Brands, history professor and author of many biographies about U.S. presidents, including Woodrow Wilson. “He was infatuated with her and she was infatuated with his power. But he was charming besides.”

Wilson writes of Galt: “…my pride and joy and gratitude that you should love me with such a perfect love are beyond all expression, except in some great poem which I cannot write.”

It would appear that some of the best love letters are not only written by the poets, but by the politicians.

Featured in the First Lady’s Gallery of the Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library and Museum on The University of Texas at Austin campus are the love letters between LBJ and Lady Bird Johnson from their courtship. She was attending The University of Texas at Austin at the time, and graduated in 1934 with a bachelor of arts degree in history and a bachelor’s of journalism.

In the fall of 1934 he wrote to Lady Bird: “This morning I’m ambitious, proud, energetic and very madly in love with you…I haven’t had a letter from you since Saturday…Not fussing just checking up on Uncle Sam’s efficient postal service.”

Further proof, that the only thing better than receiving a love letter, is receiving another.