Historian Sees Beauty Shops as Birthplace of Activism

“While there is a very vibrant scholarship in African American history and African American women’s history, the issue of entrepreneurship is something that has sometimes been ignored,” says Tiffany Gill, while sitting down with us to discuss her book, “Beauty Shop Politics: African American Women’s Activism in the Beauty Industry”. “I wanted to add to that discourse.”

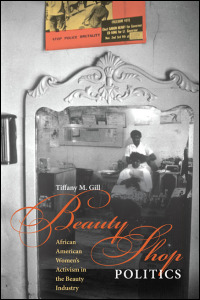

In the book, published this spring by University of Illinois Press, Gill, a University of Texas at Austin assistant history professor, shows how black beauticians throughout the 20th and early 21st centuries turned their beauty parlors into platforms for social, political and economic activism. The beauty shop gossip took on a new vibrancy, and the women whose lives were limited by the racial and economic injustice of the Jim Crow era used what they knew to stimulate change and to create the modern black female identity.

“I hope it encourages all of us to think about the seemingly frivolous spaces — to look at places where we engage and interact with one another and to see them for their full potential,” says Gill, who is also affiliated with the Center for Women’s and Gender Studies and the Warfield Center for African and African American Studies.

Taking time away from her newest project, examining the birth of an African American international tourist industry in the postwar era, Gill explains her decade-long research process, favorite memories and hopes for the book.

What was your motivation for writing this book, and what do you hope to see result from its publication?

It’s one of those things I stumbled on. A lot of times I get asked if I had a latent interest in beauty shops or beauticians, but that wasn’t it at all. It was just that this is such a great space to discuss the things that have been most important to African American women throughout the 20th century.

I wanted to unearth stories of African American women within their political lives, their entrepreneurial lives, and this topic was one that allowed me to look at and examine a lot of things that I’m really interested in — business, politics, issues of representation. Analyzing beauticians and beauty shops allowed me to work through all of those issues.

Can you describe your research process for this book?

A lot of it was done as archival research in museums and libraries looking at collections from African American beauticians starting in the early 1900s — the papers of well-known beauticians like Madam C.J. Walker, who developed her own line of hair products, to lesser known beauticians whose papers I found. I started archival research in the fall of 1999, so it has been over a decade of slowly piecing it together. It’s taken me to some really interesting libraries and archives, everywhere from Washington, D.C., to San Diego, to Chicago, to Atlanta, to New York, to Houston and every place in between.

The first place I did research was down in South Carolina where there was a beautician named Bernice Robinson. I thought at first that I would talk about Robinson and the type of political work that she did down in South Carolina during the 1950s and 1960s, but as I started going through her story I began to realize that there was much more to this. After broadening the scope to the national level and broadening the time period, I found African American beauticians engaged in political struggles and active in their communities based on the fact that they were economically autonomous and had access to African American women as clients.

So originally what I thought was going to be something very narrow became a much bigger project than I had ever envisioned for it. It’s been a long journey, learning as I go, but it’s been really fun to travel the country, to dig around and to talk to people.

What was one of your favorite moments in researching for the book?

I was out in San Diego where there is a project still going on that links African American beauticians with health advocates and health educators from the University of California San Diego Moores Cancer Center, using beauticians as front-line community health educators. I had the opportunity to go to various beauty shops where these beauticians were engaged in everything from handing out information about breast cancer to encouraging their clients to go for yearly mammograms and pap smears. I interviewed all these women in their beauty shops because they are busy and I didn’t want to take time out of their working schedule. I got to talk with their clients as well.

As I was talking to one beautician about how she got interested in health advocacy because of a close family member who died of breast cancer, her client in the chair started sharing about her own journey with breast cancer as well. It was an unscripted moment that really didn’t get included in the book, but to me it highlighted just how important the roles of these women are. The beauty shop is a very safe place for women to talk, so why not marry it to things like health advocacy and politics and things that are very important to women’s lives? It was a lot of fun listening to the kind of impact they were able to have as beauticians in their community and as health advocates.

Beyond opening beauty salons as entrepreneurial ventures, what was the role of the beauty salon in the lives of African American women trying to make their voice heard in the public sector?

I think part of the function of beauty shops, particularly for African American women in a society that did not value them, is that they gave these women this one space where they were valued and where they could literally let their hair down — somewhere to relax. But it wasn’t just about the pampering or the informal gossip, but that out of it they organized and made a conscious effort to use their spaces to impact their larger communities. Beauty shops were empowering spaces for women, who were engaged in such difficult labor in their daily lives, to talk with the beauticians whom they trusted and whom they saw as community leaders. All of that together made for really interesting things to happen. I was shocked every time I would read about another manner in which these women were using these spaces in the most creative and interesting ways.

What do you think readers will find most surprising about the book?

I ask people that a lot, and I think mainly they are surprised by the scope and the varied things that were going on in beauty shops throughout the 20th century that had absolutely nothing to do with hair. I also think they will be surprised at just how intentional beauticians were in using their space for political and health engagement and how these shops were linked to a national network. Women were often taught in beauty colleges how to engage their clients politically. This was not something that was happenstance, but rather this was something that was very intentional, very thought-through, very much organized at the local, state and national level. It surprised me and I think it surprises most readers as well.

“Beauty Shop Politics: African American Women’s Activism in the Beauty Industry”