Training professors to write grant proposals, win research dollars

Like many young faculty members at The University of Texas at Austin, psychologist Paige Harden has big, cutting-edge research ideas.

Also like many young faculty, Harden needs federal grants to get started. But she realizes that the average age of scholars who receive certain National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants is 43 years old.

“I’m in my late 20s. I can’t wait 15 years,” says Harden, an assistant professor in psychology and the Population

Research Center (PRC) who is working with a colleague to develop a registry of twins in the Austin area. “The twins project could be really incredible research. But I need money to make that happen.”

That’s why Harden and three PRC colleagues spent last summer in grant-writing boot camp, an intensive program that trains faculty members to secure competitive federal research dollars.

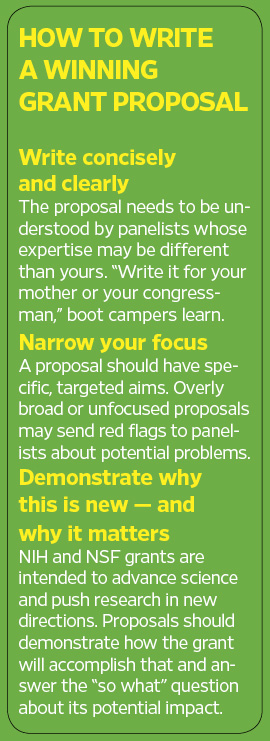

Run by PRC Director Mark Hayward, boot camp drills the mechanics of applying for grants into the minds of young professors: be clear about your aims, present ideas concisely and understand the audience that will be reviewing the proposal. The decade-old program also promotes an honest give-and-take among instructor and participants, encouraging them to challenge each other’s ideas and push one another to become better.

“A lot of people have good ideas. But many young researchers don’t know how to sell or frame those ideas. They don’t learn that in graduate school, where they’re focused on a research product rather than getting support for it,” says Sociology Professor Robert Hummer, a former PRC director who helped create boot camp. “We try to help people here take their raw ideas, package them and make them competitive.”

Boot camp graduates include Robert Crosnoe and Kristine Hopkins, sociology professors who have emerged as top scholars in their fields. And the model has inspired other liberal arts departments — and other universities — to begin training their young faculty on how to apply for grants from the NIH or National Science Foundation (NSF).

Those grants are the lifeblood of social scientists.

They can run from tens of thousands to millions of dollars and are among the only sources of funding for U.S. scholars to conduct long-term research in such areas as human behavior, demographic trends or child development.

They are also the lifeblood of the PRC, which brings together scholars from different disciplines to study demographics and relies on federal dollars for almost all of its research. The center receives $5.5 million a year in federal grants.

The university received $376 million in federal funding in 2008-09, including $65 million from NIH and $79 million from NSF. Those numbers have increased over the past two years.

“If our faculty doesn’t do this,” says Hummer, “we go out of business. These grants help decide what science is getting done in the country.”

So, of course, the competition is fierce.

Fewer than 10 percent of NIH applicants and about 20 percent of NSF applicants receive funding. And often, young professors must go up against Nobel Prize winners and other giants in their fields to secure grants. “Getting NIH funding is getting even tougher,” says Hayward. “So putting them through the pain of boot camp is a good idea.”

“Write it for Your Mother”

The idea for boot camp was born in the late 1990s when the PRC, originally established in 1960, lost some of its NIH research funding. About a half dozen faculty members had active federal grants but there was no young blood coming into the center and little effort to cultivate new research, Hummer says.

So then-Director Myron Gutman, a history professor, invited several junior faculty members to spend a summer brainstorming ideas and developing grant applications.

When Hummer became director in 2001, he obtained NIH money specifically to increase the center’s productivity and teach new faculty to apply for federal funding. Boot camp was up and running.

Crosnoe was among the early participants.

A Stanford graduate who came to The University of Texas at Austin in 2001, he remembers that senior faculty gave him about a year to get settled.

“At the end of the first year, they said ‘you’re ready. You should go ahead and do this,’” he says.

Crosnoe — who had already received a private foundation grant for young scholars — wrote a proposal to study the mental health and development of teens who don’t fit in during high school. He was awarded an NIH grant, which has led to other grants, several studies and a book to be published this spring called “Fitting In, Standing Out.”

But the implications of his research weren’t as obvious nearly a decade ago when he wrote his first draft of the application. It sounded like a good academic journal article, he was told, but not a proposal that could win large amounts of federal dollars.

“I remember Bob Hummer asking why the average person on the street would care about identity development,” Crosnoe says.

So he and his colleagues talked about why it mattered. With the Columbine High School shootings still fresh in the public’s mind and the No Child Left Behind Act having just passed, Crosnoe began to see the larger policy implications of his work and focused on them in his application.

“With federal grant proposals, the hardest thing to write is the first page. You have to have a hook and convey why your project is important in terms the non-scientist would understand,” he says. “I learned you have to write it for your mother or your congressman.”

NIH and NSF applications are reviewed by panels of scientists who may not be from precisely the same field as an applicant. So demonstrating why a proposal is relevant or groundbreaking is vital, says Kristin Weidman, manager of the College of Liberal Arts’ Pre-Award Grants Office.

“You need to drive that home: What’s new and novel, what does this bring to the field?” says Weidman, who has led grant writing workshops similar to the PRC boot camp for such departments as Anthropology, Linguistics and Government.

Crosnoe says colleagues at the University of Michigan and Johns Hopkins have spoken with him about developing their own programs.

“One of the things we’ve found really helpful in these workshops is the peer review process,” says Weidman. “People are often narrowly focused on their field. They’re not sitting around and hashing out ideas with a group. This allows them to do that.”

Around the Table

On the 27th floor of the Tower, last year’s class of boot camp participants gathered around a conference table one morning to hash out such ideas. Wearing shorts and T-shirts, looking at their laptops, the faculty members were collegial and supportive but also direct and honest.

“Whatever you do, it’s got to be shorter pages. And there’s a lot of room to cut in here,” Hayward told one assistant professor before inviting his junior colleagues to “be vicious” about a proposal he’d written a few years earlier.

“You need more headings,” Harden offered, “and it has to be clear what’s new here.”

Harden and her boot camp colleague, Psychology Assistant Professor Elliot Tucker-Drob, hope to secure federal research dollars to build a database that will track twins’ behavior, experiences and accomplishments over time. Such a registry would help the researchers study how genes and environments interact to influence human development. One of Harden’s areas of expertise is alcohol use among adolescents. One of Tucker-Drob’s areas of expertise is cognitive development and academic achievement. (See page 7)

Their registry would provide data for other researchers to examine the influence of upbringing, family and other factors in children’s lives.

By the end of the discussion the pair had developed a plan for their application, agreeing to go the “scientific route” — pitching the immediate scientific importance of a registry — as opposed to the “infrastructure route” — pitching it as a way to build a tool for research.

As part of boot camp, Harden, Tucker-Drob and the other participants also completed individual proposals for an R-01 grant, the standard NIH research grant that can provide up to $500,000 a year for five years. The R-01 application was recently cut from 25 to 12 pages, making concise writing even more valuable.

Other boot camp participants last year were Leticia Marteleto, an assistant professor of sociology, who is studying racial disparities in Brazil’s educational system, and Aprile Benner, a PRC postdoctoral fellow in human development looking at the connection between school diversity and mental health. Coincidentally, they are all interested in studying twins as part of their research.

When senior faculty talk about federal grants, they like to say the odds are stacked against them and they use other gambling metaphors.

“It was all or nothing, we needed to roll the dice,” Hayward says of a proposal he once submitted.

“It’s high risk, high reward,” Hummer says of one type of federal grant.

But through boot camp, the professors are able to change the metaphor and turn a high-risk gamble into a smart investment. They spend time and money on young colleagues now to ensure those budding scholars will secure funding, conduct world-changing research and contribute to a well funded future at the PRC and The University of Texas at Austin.

That level of support helped convince Harden to come to The University of Texas at Austin last year.

“I was interested in a place that’s interested in helping new faculty succeed,” she says. “Boot camp helps do that.”