High school’s over, but the effects may be long term

High school is long past for Kelly, now 38, but she still recalls when her family relocated to a small West Texas town at the beginning of her freshman year. The bullying started from day one with a new rumor circulating about her every Monday morning.

“The choices were to sit at home or get punished,” says Kelly, who asked to be identified by her first name only for fear of being recognized. “I remember throwing up a lot from the stress. I tried to be out sick every single Monday.”

With bullying reaching a crisis level in U.S. schools, University of Texas at Austin sociologist Robert Crosnoe has completed one of the most comprehensive studies of the long-term effects on teenagers who say they don’t fit in. His new book “Fitting In, Standing Out” (Cambridge University Press; April 2011) provides new and disturbing evidence that socially marginalized youth, including victims of bullying, are less likely to go to college, which can have major implications for their adult lives.

“Because social experiences in high school have such demonstrable effects on academic progress and attending college, the social concerns of teenagers are educational concerns for schools,” says Crosnoe, a professor in the Sociology Department and faculty affiliate in the Population Research Center.

In writing his book, Crosnoe researched national statistics from 132 high schools and spent more than a year inside a high school in Austin with 2,200 students, observing and interviewing teenagers.

He found that feelings of not fitting in led to increased depression, marijuana use and truancy over time, which were associated with lower academic progress by the end of high school. That, in turn, lowered students’ odds of going to college.

Girls were 57 percent and boys 68 percent less likely than their peers of the same race, social class and academic background to attend college if they had feelings of not fitting in, Crosnoe found. Girls who were obese or reported being attracted to the same sex were far more likely to feel that they did not fit in and experience the negative consequences of these feelings.

“Kids who have social problems — often because they are overweight or gay — are at greater risk of missing out on going to college simple because of the social problems they have and how it affects them emotionally,” Crosnoe says. “Not because of anything to do with intelligence or academic progress.

“When you feel different because of what is happening to you in high school—real or imagined — that is messing up the identity development process, which is an important part of adolescence,” he adds.

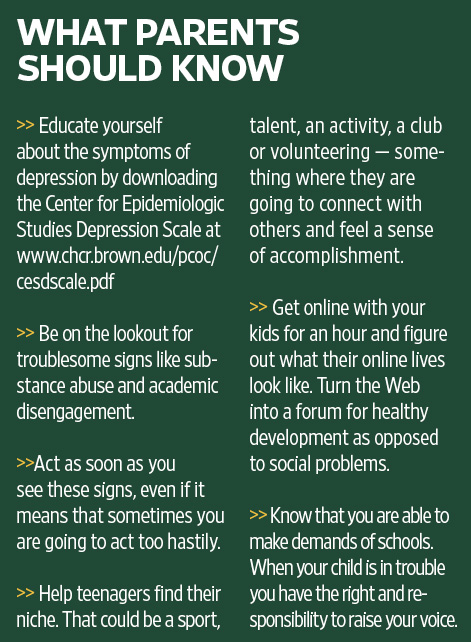

Crosnoe’s research, funded by the National Institutes of Health and William T. Grant Foundation, has resulted in theoretically and empirically grounded recommendations for how parents, teachers, policymakers and other adults can ensure that the social side of high school supports, rather than undermines, the academic side of high school. It could have tremendous implications in terms of the health and safety of students, as well as their future health and wellbeing.

Educators and policymakers are increasingly focused on anti-bullying efforts, with the White House recently hosting a summit on the issue and Texas lawmakers considering tough, anti-bullying legislation.

Crosnoe says teenagers cope with the discomforts of being bullied in ways that are protective in the short term, but disastrous in the long term. Those coping strategies interrupt the educational process — the classes they take, the grades they make — which, in turn, affect their ability to go to college.

Teenagers are forced to navigate the complex social hierarchy of high school where they run the risk of either being prized for being “real,” or punished for being too different.

Kelly, who describes herself as having been a tomboy in high school, says she thought conforming and dressing like everyone else would help her fit in.

“My hair got bigger, it was the 80s after all, and I had to have a new outfit,” she says. “I thought if I looked great, things would get better, but it probably made it worse.”

Crossing the Line

Adults may view bullying as a timeless, ultimately harmless, rite of passage. But recent changes in American society and technology are intensifying this rite, making bullying inescapable and allowing its effects to cascade into adulthood.

“There is a widespread belief among adults that ‘it’s just high school, everybody goes through it, you’ll get over it,’” Crosnoe says.

“My parents said I wasn’t giving it enough time,” Kelly says. “No big deal. They had no clue, even when I talked to my mom about it.”

It wasn’t until a classmate used a spare key she had found to break into Kelly’s house that her parents’ understood the

seriousness of the situation.

“My stuff were the only things touched,” says Kelly. “It was a lot of teenage jewelry that was taken. You would have needed a magnifying glass to see the diamonds and there were big, fluffy, heart-shaped sterling silver jewelry.”

The next week at school Kelly discovered the bully had been showing off her stolen belongings to other girls.

She endured a long list of abuses that included being humiliated in public, being physically pushed, and having clothes and jewelry stolen. Ultimately, though, it was the malicious rumors — typically sexual in nature — that haunted her in the long term.

“One thing I learned is that you shouldn’t believe everything you hear,” Kelly says. “Rumors would circulate about me when I wasn’t even in town, but people would still listen, still believe, because of who said it.

“It makes me not trust people,” she adds. “Especially new people; not until time passes.”

Fortunately for Kelly, her dad transferred jobs and the family was able to move before her junior year. She had a much better experience at her next school and went on to earn a master’s degree in psychology. As a parent, she says she will be diligent about advocating for her two daughters when it comes to bullying, so they will never have to experience what she went through.

But for many victims, moving away is not an option.

Building a Good Defense

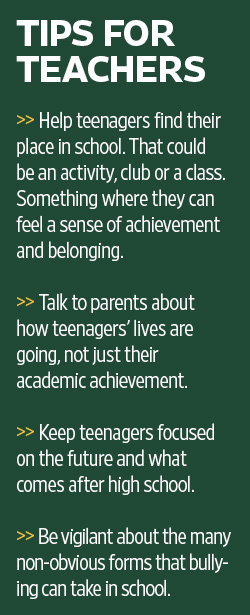

One of the only things that can help a student who is being marginalized or bullied by peers is having a strong adult mentor to whom they can turn and trust. Crosnoe says teachers are prime candidates for the job.

“Teachers are often the last line of defense for kids who are having social problems in school including being bullied,” he says.

Nan-Hee Aguilar, a teacher for the past 13 years, tries to set the tone of trust, support and open communication with students and parents at the beginning of the school year. She worries that students with low self-esteem may be afraid to speak up to a parent or teacher when they are in trouble.

“I’m constantly having to find ways to bring up the self-esteem,” says Aguilar who has taught in Dallas, Fort Worth, Arlington and Austin. “Anytime I catch wind of bullying, I try to do an intervention, even if it’s subtle bullying.”

She does so by using character-building curriculum in the classroom, moving where the students sit if there is a problem, informing the parents, and constantly monitoring the situation.

“It’s my job to make sure that child is comfortable at school and to provide a safe environment,” Aguilar says. “If not, the students are not going to want to come to school.

“I’ve seen bullying affect them in so many ways,” she says. “Regular A students who no longer want to come to school, are not motivated to do as much and who don’t want to complete work.”

While so much content on television and the Web is about outrageous acts of bullying and physical aggression, much more is hidden in the social warfare of school. Things like backhanded compliments, snubbing, looks of disapproval and disgust in the hallways.

“It sounds so silly especially compared to those classic forms of bullying,” Crosnoe says. “But these are the things that really matter in the long term because they are subtle. They can get under a teenager’s skin and become a preoccupation causing them to doubt themselves and distracting them from what school is supposed to be about.”

This is especially true for girls who are obese, who are 78 percent less likely to attend college than non-obese girls, and those who are gay, who are 50 percent less likely to attend college.

Crosnoe recommends keeping teenagers focused on the future, whether it’s going to college or getting a job. Parents and teachers can do this by encouraging their teenagers to keep talking about their aspirations as a reminder that high school is just a blip in their lives. And there is much more to come.

Aguilar says the biggest challenge is to reassure students that everything is going to be okay, and that the hard times will pass.

Ava’s Story

A very smart 9th grade student, a self-proclaimed band nerd with social problems, caught Crosnoe’s attention during his research, at first because not fitting in really didn’t seem to bother her.

“She said she didn’t care and being different was actually something she aspired to be,” says Crosnoe. “The fact that she was an outcast was a sign that she was doing something right — that she was being true to herself.

“I admired her and thought she was courageous,” adds Crosnoe, 39, a native of Wichita Falls. “So much so that I thought ‘I wish I had been more like her myself 20 years ago when I was going through my ups and downs of high school life.’”

But the more he got to know Ava, a different picture emerged — something more complicated and, in the end, more real.

Ava dreamed of moving away and wrote that she would finally have a place where she belonged and where people would accept her. Her biggest fear was being alone.

“She told me she wished she could wear a mask so no one would ever know it was her, she could be anonymous, and no one could see inside of her,” says Crosnoe.

“In the end I felt like Ava was a lot more like the high school me than I first thought. I think a lot of people reading ‘Fitting In, Standing Out’ are going to see themselves in Ava.

“Years later, I still think about her a lot,” he says, “and I hope that wherever she is now that she’s not alone anymore.”

Watch video series on Youtube