How long will you live? And how does that compare to your fellow longhorns based on your race and gender? Graduate researchers are striving to eliminate health barriers and extend life expectancy for one and all.

Life expectancy in the United States is on the rise – but not for everyone. Although many older Americans are healthier and more prosperous than any previous generation, rates of gains are inconsistent between the genders and across education levels and racial and ethnic groups.

Graduate student researchers at the Population Research Center (PRC) are working toward understanding these health disparities that continue to persist and grow in the United States, and to help extend our most precious resource: human life.

To help them succeed, Mark Hayward, Robert Hummer and Debra Umberson, professors in the Department of Sociology and Population Research Center, created research lab meetings, scientific forums that allow graduate students to present their research and brainstorm ideas with their colleagues. Every two weeks the students and professors come together to vet new ideas, critique research projects and discuss papers in progress.

Since the lab meetings were created in 2005, Hayward says he has seen many of the participating students publish papers in top sociology, demography and health science journals, win prestigious fellowships, and go on to academic positions at top tier research universities.

“These lab meetings are a tremendous vehicle for professional socialization and mentoring,” says Hayward, director of the PRC.

The following stories profile just a few students and recent alumni who have benefited from the research lab meetings and are on their way to advancing the field of population health.

Finding the Link between Early Childhood Environments and Adult Longevity

While searching for a doctoral program, Jennifer Montez had her pick of some of the nation’s most prestigious research institutions. Determined to find the right match, she spent many painstaking hours researching schools and combing through faculty bios.

One school in particular stuck out in her list.

“I was attracted to UT because its Population Research Center has some of the world’s best scholars in population health disparities,” Montez says.

Impressed by the PRC’s international reputation for producing top scholars in the field of sociology, Montez called Robert Hummer, who was the department chair of sociology at the time, to get more information about the program.

“He spent over an hour with me talking about the pros and cons and sent me all kinds of information about the research opportunities I could have if I came here,” Montez says. “Knowing that the department head was willing to talk to a potential grad student for over an hour was the deciding factor. Immediately after I hung up the phone, I turned in my acceptance letter.”

While at The University of Texas at Austin, Montez has published several papers in top demography and population health journals. She says many of her studies took shape in the research lab meetings.

“The research meetings keep us together as a community — and the faculty treat us like colleagues rather than students,” she says. “It’s also a great way to showcase how faculty and students collaborate when candidates come to campus.”

A specialist in social demography and adult mortality, Montez is currently researching a phenomenon known by sociologists as the “gender paradox.” “

Although women tend to live longer than men in the United States, they have more chronic health problems, such as arthritis, later in life,” she says. “This is one of the biggest puzzles in our field. What is it about women’s lives that disadvantages their health? We’ve been studying this puzzle for decades but we still cannot fully explain the male-female health gap.”

To understand why more women than men suffer from chronic ailments during adulthood, Montez is exploring the possibility that conditions early in life — as early as in utero — cause poor health outcomes for women in particular.

“We are increasingly recognizing how critical early life is for later life health,” she says. “You just can’t undervalue the importance of experiences such as proper nutrition and a supportive home environment for children. We might think that we’re more resilient than we are and that we’ll make up for it later down the road as adults, but early life is such a critical period. Early experiences seem to ‘get under the skin’ in ways that permanently shape our physiology, for better and for worse.”

After completing her doctorate in sociology from The University of Texas at Austin in spring 2011, Montez is continuing her research at Harvard University as a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) Health & Society Scholar. The fellowship is the most prestigious postdoctoral award in the field of population health.

Bridging the Black-White Mortality Gap

According to the National Center for Health Statistics, African Americans, on average, die five years earlier than whites. White life expectancy is 78.2 years, while for blacks it’s 72.9.

Troubled by the persisting black-white disparities in health and mortality, Ryan Masters, who received his doctorate in sociology in spring 2011, focused his doctoral research on historical trends in U.S. health and mortality disparities across racial and educational groups.

One of his studies examined the puzzling finding that African Americans have lower death rates in vital statistics data than whites after age 85. Researchers have questioned whether this is a result of poor data quality or whether it stems from a highly robust group of older blacks.

In a forthcoming paper in Demography, a leading academic journal, Masters shows how the crossover is largely an outcome of “differential selective survival” (a sociological term that explains skewed mortality data) for blacks and whites.

According to his research, African Americans experienced substantially higher death rates than whites throughout adulthood, which resulted in an unusually robust group of blacks who survived to old age.

Masters was also awarded the RWJF Health & Society Postdoctoral Fellowship and is continuing his research at Columbia University. Masters and Montez were two of 12 RWJF fellows chosen nationwide in 2011, an extraordinary accomplishment given the hundreds of high quality applicants.

Masters attributes much of his success to his fellow researchers and mentors, Hayward and Hummer, who helped him flesh out his projects in the research lab meetings.

“The lab meetings give us the space to actually research and discuss the most pressing questions in our field,” he says. “All they ask in return is for us to meet them halfway with a solid work ethic. It is a remarkable setup for academic work, and I have benefited tremendously from it.”

At Columbia University, Masters is broadening his work into the area of health policy. He also is investigating the key historical advances in public health and nutrition between 1910 and 1940 that led to the remarkable declines in mortality rates in the United States.

Investigating a Puzzling Paradox

The “Hispanic Paradox” has long challenged conventional thinking among sociologists and public health researchers. It is based on the idea that Hispanic-origin people residing in the United States live, on average, longer lives than whites, who have much higher average incomes and educational levels.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, Hispanics have a life expectancy of 80 years. That compares to about 78 years for whites and just under 73 years for blacks. Hispanics are less likely to have health insurance, yet they are less likely than whites to die from heart disease, cancer and strokes — the leading causes of death in the United States.

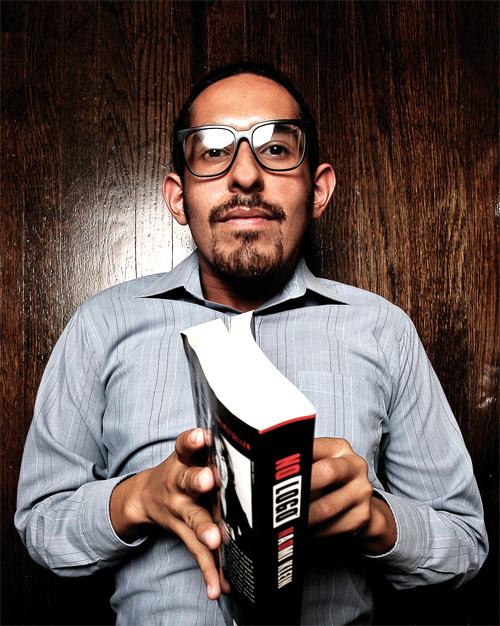

Connor Sheehan, a graduate student in the Department of Sociology and the PRC, aims to find some reasons underlying the paradox.

With a focus on U.S. health disparities between whites and racial and ethnic minorities, Sheehan is developing a multi-methodological approach to his research. Although it may take years of research, he hopes his findings will help eliminate disparities in mortality.

By working with some of the nation’s leading sociologists at the PRC and participating in the lab meetings, he says he is on his way to accomplishing his goals.

“The UT Sociology Department continues to be highly regarded,” says Sheehan, who joined The University of Texas at Austin in fall 2011 after completing his master’s degree in geography at the University of Colorado. “They have an impressive number of faculty who are conducting research at the forefront of their respective fields, and the graduate program has an outstanding placement record.”

Eliminating Barriers to Good Health

In an ideal world, all communities would have access to fresh produce, safe playgrounds and walking trails. However, these resources are few and far between in underserved communities throughout the country.

To understand how community and space affect health outcomes, Phil Cantu, a new graduate student in the Department of Sociology and PRC, is studying health disparities among poor minority populations, specifically Hispanics.

After earning his undergraduate degree in sociology from Southwestern University in 2008, Cantu worked with several local nonprofit groups addressing economic and social justice issues in underserved communities. While conducting a health survey in East Austin, he found that his project was stultified by substandard research design.

“The research design for our project was really poor,” Cantu says. “I decided the best way to pursue that line of inquiry was to go to grad school and use these tools and methods that have been proven over time.”

After attending one of the research lab meetings during a recruitment event, he knew the Department of Sociology and PRC at The University of Texas at Austin was the best fit for his academic interests.

“The co-authorship between the students and professors here at UT is astounding,” he says. “They help prepare students for getting those really good post-doc positions. The focus on ideas is what really excited me about this program. I think that’s the most important thing professors can give their graduate students, and it’s the most important thing they can get out of graduate students.”

Cantu says he was also enticed by the new Liberal Arts building, which will house the PRC in 2013.

“I’m very excited about the new building, which will provide us more space for new collaborations and exchanging ideas,” Cantu says. “The fact that the college is making this building a priority speaks volumes about the importance of the Population Research Center.”

After earning his master’s degree, Cantu plans to work toward a doctoral degree at The University of Texas at Austin and later pursue a career in demography.

“UT has a history of producing really strong scholars in the field of sociology,” Cantu says. “And I would like to continue that tradition.”