Presidential scholar discusses war power and accountability

Many Americans believe that the growth of presidential war power relative to Congress is irreversible. Bruce Buchanan, government professor at The University of Texas at Austin and one of the nation’s leading presidential scholars, contests that view.

In his latest book, “Presidential Power and Accountability: Toward a Presidential Accountability System” (Taylor & Francis, Inc. Aug. 2012) he proposes a plan that will allow presidents to deal with emergencies without permanently altering the constitutional balance of power in the process.

I recently spoke with Buchanan about the steps necessary to restore balance and why “wars of choice” are the most important problem facing the balance of our presidential accountability system.

What is a “war of choice,” and why is it considered the most-important problem facing the checks and balances of the presidential accountability system?

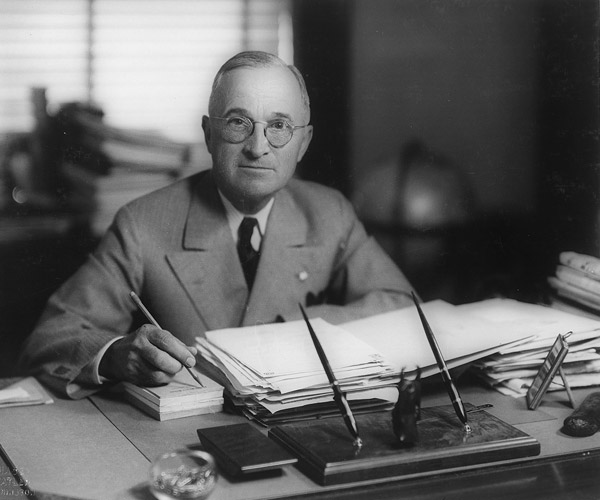

It’s a conflict initiated by a president against nations that haven’t attacked the United States. I think it’s the most important problem, because since Truman sent troops to Korea in order to repel the invasion of the South by the North — and did so without consulting Congress — that unilateral action has come to be seen as a precedent that has altered the constitutional balance of power, in effect, by taking away Congress’ power to authorize war. Now it’s up to the president, and everybody just accepts that.

You suggest the remedy is to turn to prospective rather than retrospective accountability. Can you explain?

That is for a special category of problem, the “war of choice” problem where we haven’t been attacked. There are certain kinds of crises like the Civil War or Pearl Harbor where presidents necessarily act without checking with anybody and that should continue. I don’t contest that. Presidents have to be free to do whatever is necessary to preserve, protect and defend the country.

But in cases where it’s a “war of choice,” when the United States has not been attacked, there usually is time and no good reason not to convene a congressional proceeding that could impose prospective accountability by vetting or debating the president’s war policy before it is implemented.

You recommend policy trials as a vehicle to provide prospective accountability. What are they modeled after?

They’re modeled on the impeachment process described in the Constitution. That’s the model, but the big difference is that the president is absolutely not on trial; it’s the war policy.

I have a final chapter in the book where I put Barack Obama’s proposed Afghanistan troop increase; his “escalation of choice” through a hypothetical fictional policy trial to show how they would work.

It’s a process where the emphasis is on the president making his case against equally well-informed critics who get equal time to rebut the president in front of Congress, with all of it televised live to the American people.

It’s very different from the kind of thing that happened when LBJ persuaded the people we needed to go to war in Vietnam, or when President [George W.] Bush persuaded Americans that we needed to invade Iraq because they ostensibly possessed weapons of mass destruction.

That’s the difference, to make it less about emotional manipulation and more of a careful consideration.

What are some of the benefits to this approach?

It’s careful review of the merits; that’s the first advantage. The second advantage is — and this is why it’s not harmful to the president — the president can win this trial. If he does, then what he wins is likely to be a more durable brand of political and popular support even if the war news turns bad.

Every president from Truman to Johnson to the second Bush experienced the war news turning bad. What I’m suggesting is if the people and the Congress endorse going to war after a careful argument rather than a high-pressure selling job, then that’s a form of buy-in.

Suppose the president loses. Well, then he’s off the hook. He can’t be held accountable for whatever happens because he proposed what he thought was the right thing and he lost, so it doesn’t necessarily hurt him politically at all and it may — it certainly would have in the case of Truman, LBJ and George W. Bush — have helped them to dodge what turned out to be a very significant bullet.

Was there a potential for a full and fair prospective review in the months leading up to the invasion of Iraq?

There wasn’t and here is why. Number one, we were close to 9/11, and there was an anxious and fearful mood within the country, which made the public not terribly skeptical about a president’s arguments that we ought to get involved.

Number two, we were close to a midterm election at that point. The public was supporting Bush in the 80-90 percent range — they were still scared from 9/11. Even people who would later come out in strong opposition to the war, such as Hillary Clinton and John Kerry, who were members of the Senate, voted in favor of this resolution that Bush got through in that climate. Though each still defends that vote, I suspect that both of them have regretted it ever since. The mood in the country was agitated and disturbed, and that’s why it wasn’t a real debate; it was a stampede based on fear.

Third, the president made it clear; he is on record as having said “I don’t want to debate this with you, I just want your vote.” And he could say that because of the situation. Bottom line, there wasn’t going to be a full and fair hearing.

Tell us about your concept for the Presidential Accountability Project (PAP)?

It will be a think tank, modeled on research organizations like the Government Accountability Office, the American Enterprise Institute and the Brookings Institution: public and private research organizations with different strengths but strong reputations for solid analysis.

Its main work over time will be to help our presidents and citizens benefit from the experience we’ve already had and the mistakes we’ve already made in response to wars and other crises. It will do so by conducting deep background research on issues showing what happened when presidents took actions in various situations, and what could have been done to encourage presidents to move in directions that were, in retrospect, less harmful and more useful.

What are some historical moments where presidents could have benefited from something like the PAP?

President John Adams agreed at a moment of great emotional upheaval and fear in the country to endorse the Alien and Sedition Acts, which were flatly contradictory to the Bill of Rights. In retrospect this ruined his historical reputation. And later on during World War I, President Wilson, the Congress and the courts imposed unreasonable policies for punishing what they regarded (incorrectly in retrospect) as dangerously disloyal or incendiary domestic speech against the war effort. Franklin Roosevelt put Japanese- Americans in de facto domestic concentration camps, a stain on his presidency and our record.

I think we’ve made enough mistakes — including the Korean episode — to start learning from them and putting that learning into effect. They can suggest what would be good presidential practice and reasonable standards.

How did President Truman’s 1950 decision to send troops to Korea set a precedent?

When North Korea suddenly attacked South Korea, everybody thought it was the Soviet Union using a satellite to test the United States. What that meant was if Truman thought it was desirable, he could go forward on his own and take action because no one was going to oppose it.

The thing that should have been noticed (but wasn’t) in that Korea case was the fact that Truman could have avoided setting a bad precedent. He could have easily gotten Congress’ permission in plenty of time to take the action he took. He didn’t do that because there were certain things that Truman wanted to avoid.

For example, the communist Chinese had recently taken over China, and the Soviet Union had just developed an atomic bomb. Truman was being attacked by Republicans for letting that happen, and he was fearful that if he went to Congress for approval, he would have to endure more public flogging over those issues even though there was no question that his Korean plan would be approved.

Truman’s action became a precedent because Truman’s successors, including Lyndon Johnson, saw his move as evidence of their inherent right as commanders-in-chief to deploy troops without congressional authorization. Congress has yet to effectively challenge this claim.

Shouldn’t the 1973 War Powers Resolution, created to check the president’s power to commit the United States to an armed conflict without the consent of Congress, prevent this?

Every subsequent president — whether Democrat or Republican — has considered the War Power Act unconstitutional and has simply defied it.

For example, Gerald Ford ran the Vietnam evacuation effort, which involved the use of the military to some degree without seeking a War Powers Resolution seal of approval. Jimmy Carter went in to attempt the rescue of Iranian hostages, which was a military action, without seeking congressional approval. Reagan did the same in Lebanon. He also bombed Libya and had a naval escort of oil tankers in the Persian Gulf.

The first President Bush paid no attention to it in the Panama invasion, which he authorized to take down Noriega, nor did he pay attention to it in the Persian Gulf War. Bill Clinton didn’t pay attention to it in bombing Iraq or ordering troops to Somalia, Haiti or Bosnia. This list goes on.

What would be required to restore presidential war power to constitutional specifications while leaving the president powerful enough to defend the country?

Lincoln argued that the president must be free to do whatever it takes, including violating the Constitution, when the survival of the nation and its Constitution are truly at stake. But he also argued that what the president does in such circumstances should not be viewed as establishing a precedent. It does not automatically entitle future presidents to do something similar. Once the crisis has passed, the power the president used to resolve it should “snap back like a stretched rubber band” so that the Constitution returns to its original form. In other words, emergency power is not permanent.

Both John Locke [British philosopher] and Abraham Lincoln argued that each time emergencies lead presidents to violate the Constitution, it must be justified all over again. After the emergency has passed the president must make the case to the Congress and the American people that it was truly necessary. If it’s not justified, the president would be subject to removal. That’s one of the reasons the impeachment provision is in the Constitution.

How do we, the American people, make sure the president is considering all viable alternatives before entering into war?

That brings us back to the policy trial proposal. When there is time, the policy trial can be a useful way to do this. There won’t be time if we are attacked. But if there is no attack yet the president wants to initiate military action, as in the recent example of Libya, a policy trial is a way to consider the pros and cons of what the president wants to do.

Again, this is a big departure from our usual practice of leaving optional military action entirely to the president. But by now there may be enough people who are tired of paying the price we’ve paid over the years — particularly for such large, costly and (too many) unsuccessful military escapades as Korea, Vietnam and Iraq — that a new approach may seem worth trying.

What’s the cost of not restoring balance?

Put simply, a greater risk of failure and greater costs in blood and treasure. Starting with Korea, which ended badly and ruined Truman’s political career, it was finally settled with an armistice, not an end to the war, not a treaty. It’s still going on and still a problem. In the case of Vietnam it weakened the presidency for a generation. And the Iraq war also proved costly and unpopular.

These wars [combined] cost almost 90,000 American lives and billions of dollars, with outcomes that many Americans count as failures. It introduced rancor and discord into our domestic political discourse. It made it harder for us to focus on other problems over the years, and it has put the constitutional balance of power out of whack. So the cost has been really quite enormous.