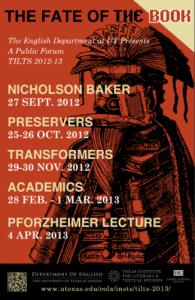

Public forum series examines the uncertain future of the book

The Harry Ransom Center’s Gutenberg Bible is among the world’s most valuable books. Printed more than 550 years ago, it is one of only 21 complete copies known to exist.

To discover an intact copy today would be a rare find, but not as rare as an original set of New York World newspapers. Read daily by more than a million people in the late 1890s, few intact sets exist today.

“American newspapers were bound into books by farsighted librarians,” said author Nicholson Baker at the Sept. 27 opening lecture of the Department of English’s yearlong “The Fate of the Book” symposia, sponsored by the Texas Institute for Literary and Textual Studies (TILTS) and co-directed by Janine Barchas and Elizabeth Scala, both associate professors of English.

According to Baker, many of these carefully and often beautifully bound newspapers, along with thousands of books, magazines and other printed materials, are now rotting in landfills across the country. He says they are victims of certain librarians—obsessed with technological fads—who overstated the need to clear shelf space and replaced thousands of books and periodicals with inferior microfilm or digital facsimiles.

“We don’t want to give the future our own transformed version of our time,” said Baker, who showed slides contrasting the details and vibrant colors of original 1890s pages from the World with murky black and white microfilm copies of the same pages that “replaced” them a century later.

“A purely digital culture is an impoverished culture,” said author and publisher Kathleen Rooney at The Fate of the Book’s Oct. 25 panel that focused on preservation. “Context is more important than just ‘the Internet,’ which is just data without an embodied form.”

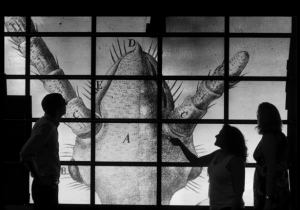

Fellow panelist Michael Witmore, director of the Folger Shakespeare Library, again underscored the importance of a book’s physicality, noting that a  book, particularly one in decay, makes us pay even greater attention to it.

book, particularly one in decay, makes us pay even greater attention to it.

“Like a candle, a book must be used to exist. Every time it is used, a little disappears, but the more it is used the brighter it burns,” said Witmore. “People need to see the special light cast by these objects. Only by letting them be seen and be used can we save them.”

And as Baker observed in his 2001 book Double Fold, despite years of use old volumes of newsprint that have escaped the landfill seem to be doing a better job of holding their original images than their plastic microfilm reproductions. To a reference librarian who told Baker that hard copies “just don’t keep,” Baker offers this rejoinder: “They don’t keep, kiddo, if you don’t keep them.”

Baker also said there is no reason why various media have to be viewed in opposition.

“Why can’t e-books and film and real books co-exist? The great thing about digital and microfilm is they can be widely distributed, but the original needs to be kept. We need to always know that the facsimile is faithful to the original,” Baker said.

A “Transformer Panel” discussion at 7 p.m. on Nov. 29 at the Ransom Center is the next event in “The Fate of the Book” symposia series. See the full schedule of the series, which continues through the spring.

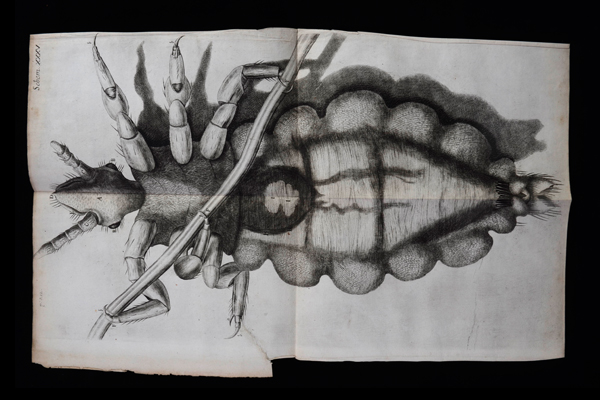

Banner image: Folding illustration “of a louse,” from Hooke’s Micrographia (2nd edition, 1667 at p. 212)