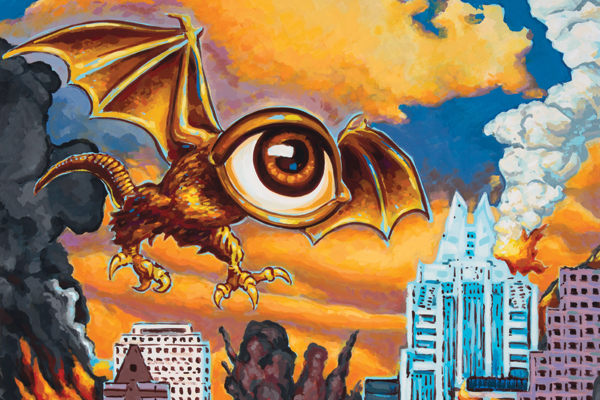

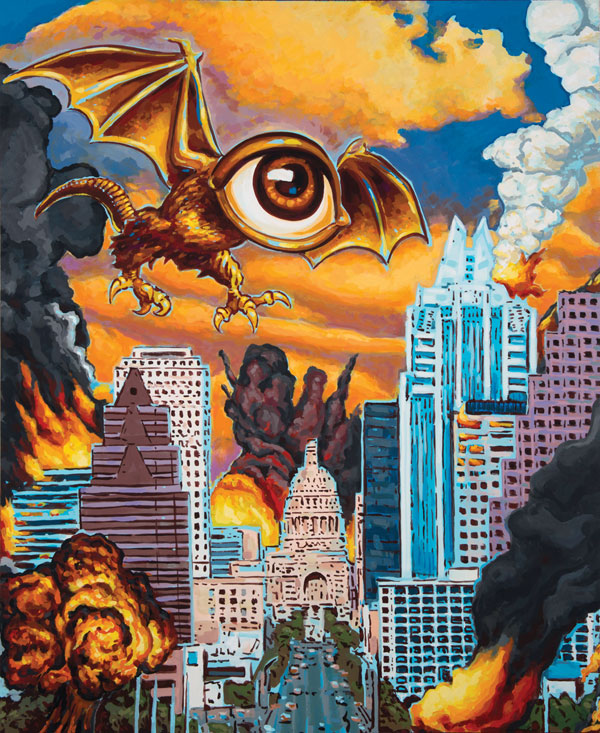

Will rapid growth destroy the city’s weird and charming vibe?

Walk by a magazine rack and take a look at the headlines. Chances are, you’ll find Austin gracing a “best city” list. Among its many accolades, the Texas state capital has been named the “best city to start a small business,” “best city for retirees,” “best city to find a job” and “best city for dating.”

With its scenic Hill Country landscape, world-renowned music scene and highly-educated population, it’s no mystery why Texas’ capital city is attracting young urban professionals in droves.

Forbes magazine, which named Austin the fastest-growing city in the nation, states that growth brings opportunity. But along with the economic advantages that come with popularity, many natives are worried that Austin is at risk of losing its quirky, countercultural vibe.

To start an online conversation about Austin’s exponential growth, Randy Lewis, professor of American studies, and his team of graduate students created a digital humanities project, aptly titled End of Austin. Published twice a year, the online journal features a broad range of voices—academics, students, artists, activists—who all share one common goal: to maintain Austin’s reputation for greatness.

Using photos, essays, podcasts and videos, the contributors share their perspectives on how things are changing, ending, expiring or collapsing in the midst of the city’s rapid expansion. Though the title may sound grim, Lewis says “the end” is a somewhat loaded phrase meant to encourage people to consider what Austin has been and what it’s in the process of becoming.

“End of Austin is about thinking ahead and asking important questions about what Austin is going to become when it hits 3.5 million people in 2040,” Lewis says. “Our goal is to bring the community’s voice and try to plan, dream and imagine what the future holds for Austin.”

Established in 2012, the website has amassed an impressive amount of feedback from people on both sides of the spectrum: supporters of development and economic progress, and those who prefer the quaint and quirky trappings of old Austin.

“There’s so many simultaneous feelings about loss and excitement and hope about what the city will become,” says Carrie Andersen, American studies graduate student and End of Austin editorial board member. “On our site, you’ll see it’s really complicated how people are imagining the past and the future of the city. We’re trying to dispel the notion that you can only be nostalgic and not forward-thinking, or you can only be progressive and not care about the past.”

In a city of perpetual nostalgia, many residents feel a great sense of loss when a funky neighborhood morphs into a trendy shopping center, or when an iconic fixture falls victim to zoning laws. Those deep attachments people feel toward their city can be transformed into hopeful visions for its future, Lewis says.

“We’re interested in why people talk about things they love that they are losing,” Lewis says. “And we want to see where that affection comes from—and how it roots them here in ways that are very meaningful.”

Those deep attachments are especially prevalent in the music scene, says Sean Cashbaugh, American studies graduate student and End of Austin editorial board member.

“The concerns that grow from feelings of loss can be really productive for a lot of people,” Cashbaugh says. “When Emo’s had to close and move, there was a big call-to-action response from the community. There’s a can-do spirit among artists and activists in Austin, one that can turn a sense of loss into fuel for the fire.”

The End of Weird?

With the relocation Emo’s, a popular nightspot that has anchored a string of live music venues on Red River Street for nearly 20 years, many Austin music lovers feel they are in the midst of a battle for the city’s soul. Gone are the days of cheap rent, cheap beer and late-night concerts.

Can a rapidly-growing city retain its character? What does the popular slogan “Keep Austin Weird” mean anymore?

“Not a f-ing thing,” says Kinky Friedman, Texas humorist, singer/songwriter, author and cigar enthusiast. “Pardon my Shakespeare, of course. The traffic is hellish—and most of the places I’ve liked over the years have gone belly-up. Everybody appears to be rushing around to new wine tastings and openings, but of course they can’t get there because of the traffic.”

Friedman, who ran for Texas governor in 2006, says Austin is a far cry from what it used to be back in the 1960s when he was a Plan II student at The University of Texas at Austin. Now he resides in the Hill Country, but sometimes he’ll endure the hustle and bustle of his old stomping ground to catch glimpses of what it used to be. Despite his frustrations, Friedman admits the capital city still has its charms.

“You have to expect that things are going to change,” Friedman says. “We have to embrace the future even if it slaps us in the face. Austin has all the problems that every city has with a crazy city council and taxpayers spending money on stupid things. But you can’t take away the heart of Austin. It really has a good spirit and that’s really important.”

Often seen as narcissistic and hollow, the “Keep Austin Weird” slogan reflects a genuine anxiety about the shape of things to come, Lewis says. Will the rapid growth eclipse the city’s weird and charming vibe? Is Austin at risk of losing its true identity?

According to Emily Roehl, American studies graduate student and End of Austin editorial board member, Austin’s ever-growing diverse population is too complex to be pigeonholed into one identity.

“I’m not sure it is useful to think of Austin in terms of a singular identity,” Roehl says. “Inevitably, whichever identity gets ‘retained’ may not ring true for all or even most of the city’s residents. I think it is important to have an ongoing conversation about what it is—or could be like—to live here, a conversation that is responsive to the ever-shifting nature of a growing and changing city.”

On the Rise

Despite the public outcries, beloved Austin-centric mainstays such as the South Lamar Plaza Shopping Center and the Pecan Grove RV Park have been replaced by condominium developments. Although change is inevitable, Lewis says developers need to stop and consider the longterm impact on the city’s cultural landscape.

“When we develop and build a city, we need to ask if any of these buildings will be architecturally significant in 100 years. Alongside a concern for diversity, sustainability, and thoughtful economic growth, a strong aesthetic vision is essential to any great city,” Lewis says.

To retain Austin’s unique culture, Kevin Alter, professor and associate dean for graduate programs in the School of Architecture, says developers should focus on highlighting the city’s finest qualities. He points to the recent downtown mixed-use developments, such as Block 21 on Second Street, home of the gleaming 37-story W Austin Hotel and an array of pedestrian-friendly storefronts.

“The most interesting thing about architecture is how it creates an environment that inspires compelling ways to live,” Alter says. “In Austin’s case, that’s a young, creative community, a vibrant music scene and a temperate climate that allows us to be outdoors all year round.”

Another success story, he says, is Rainey Street’s transformation from a neighborhood of broken-down bungalows to a popular nightlife destination. Formerly a sleepy neighborhood near the banks of Lady Bird Lake, Rainey Street has morphed into a hip bar scene for locals, featuring cozy bars with spacious backyards and porches.

“Developers need to think of how to engage in ways that are special about a place. A good example of this is the recent Rainey Street development. They did a great job turning a fairly low-rent area into the focus of Austin’s hip nightlife.”

Over the past decade, Alter has been impressed by Austin’s architectural progress. However, not all developers seem to have the city’s best interest at heart. That’s especially true for the high-rise student housing west of The University of Texas at Austin campus.

“West campus is lacking in sidewalks, parks and stores,” Alter says. “Students are paying too much for housing, and it isn’t a nice environment. They could have mandated great streets and public programs but instead they seemed short-sighted by short-term gain.”

Given the radical changes to Austin’s skyline in the past decade, many natives claim that their city is turning into a “little Dallas.” But like it or not, Alter says the encroaching high-rise condos, bars and shops are a big part of Austin’s future, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

“Keeping things entombed is not a healthy way to live,” Alter says. “With progress comes development—but it needs to be done in a way that contributes to a better place that has a sustainable long-term future.”

Going Nowhere

Along with urban sprawl, a major source of anxiety is traffic. Anyone who has ever experienced rush-hour traffic on I-35 or MoPac would most likely agree that something’s got to give.

“The biggest issue that is foremost in my mind is transportation,” Lewis says. “What we decide to do with the buses and the highways will shape our lives deeply. That’s the city’s Achilles heel right now. People are losing their minds when they’re out on MoPac at rush-hour.”

According to a 2012 Urban Mobility Report, released by the Texas A&M Transportation Institute, Austin drivers spent an average of 44 hours stuck in traffic in 2011. The cost of such a delay is $930 a year, topping the national average of $818.

Among the many top city lists, Austin also rates high on the 2012 Texas Department of Transportation list of top 100 congested roadways. Fourth on the list is the section of IH-35 between Highway 71 and US 183.

Given the waste of time and money, city officials are looking toward toll roads, light rail lines, biking and other forms of public transportation for solutions. Yet according to Kara Kockelman, professor of transportation engineering in the Cockrell School, the most cost-effective solutions will come from congestion pricing and mobile technologies.

The reason is fairly straightforward. Making driving less desirable can free up a lot of space on the roadways. The challenge, she says, is incorporating new lower-cost pricing and vehicle recognition technologies into high-traffic corridors and parking lots.

In addition to covering road maintenance costs, higher taxes would help reduce the supply of free parking, which would make drivers think twice about getting on the road, Kockelman says.

“If you take 5 percent of drivers off the road during congested times of day, it often amounts to more than a 10 percent reduction in travel times,” Kockelman says.

She recommends Austin look toward big metropolitan cities, such as San Diego, Portland, Minneapolis, Atlanta and San Francisco. These cities have successfully implemented some viable solutions such as bike-sharing stations, urban growth boundaries, land-use mixing, congestion pricing and demand-responsive parking prices.

Finding Solutions

So what does the future hold for Austin? Will the city build a better freeway system or buckle under the heavy pressure of rush-hour commuters? Will the skyline be recognizable a century from now, or will it morph into another sprawling megalopolis? The city’s fate depends on the decisions that are being made right now, Lewis says.

“We have the raw ingredients of a great city based on location, climate and the university,” Lewis says. “But the decisions that we make in the next 10 to 20 years will determine whether Austin will be a world-class, great city, or if it will just be another Sunbelt urban zone.”

The hope for the writers and contributors of the website is to provide a shared brainstorming forum for both the community and the university—and ultimately find possible solutions for Austin’s biggest challenges.

“The main value that underpins the whole project is trust—trust in our contributors which then carries over to trust that Austin residents will want to have these kinds of complicated, difficult and ultimately worthwhile conversations about what the city means to them,” says Greg Seaver, American studies graduate student and End of Austin editorial board member.

By opening this project to the general public, Lewis hopes to create a new model for how academic scholarship is created and shared.

“We want to show what’s possible when you connect the talent at UT with the talent that’s out in the community,” Lewis says. “The best outcome of our project is to yield not just a deeper appreciation for what Austin was and what it should be, but to also find solutions for our problems. It’s all very selfish, really. I just want to make sure my city will continue to be a great place to live.”