As “Pride and Prejudice,” first published in 1813, celebrates its 200th anniversary, Jane Austen is repackaged to appeal to a new generation of readers

On the highbrow end, organizations and libraries around the world are busy hosting academic conferences and readings to celebrate the bicentenary. On the pop culture side, Hollywood is about to release a rom-com called “Austenland,” just as the video blog series “The Lizzie Bennet Diaries” is proving a runaway YouTube sensation. For scholars like myself, such widening interest in Jane Austen opens up new audiences for our work and our classrooms. It has never been a more exciting and vibrant time for Austen studies.

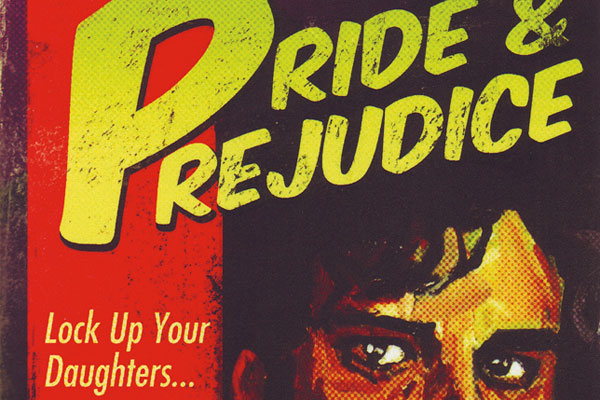

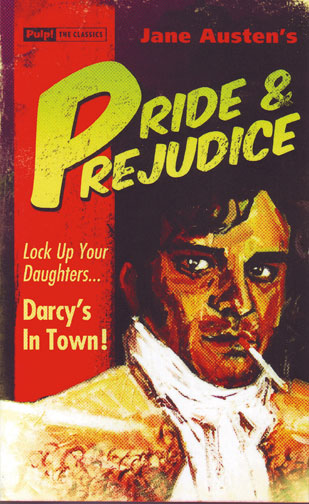

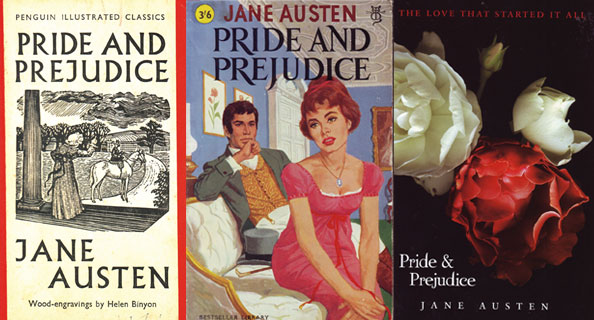

In a recent essay for the New York Times Book Review, I focused on how the history of “Pride and Prejudice’s” book cover art is another testimony to Austen’s broad historical reach. The packaging of Austen’s popular reprintings, from the 1830s to the present, show her varied market appeal and her evolving and fluctuating reputation from decade to decade.

The surprising history of the Austen cover—from Victorian schmaltz to Kindle-era nudity—witnesses an extraordinary range of marketing strategies deployed on behalf of a single author. This visual evidence suggests that Austen remixed with popular culture intermittently over the last two centuries, challenging what we have hitherto assumed was her steady upward climb toward canonicity and literary acceptability.

Austen’s legacy of adaptation, merchandizing, and irreverent homage (including radical mashups like “Pride and Prejudice and Zombies”) may show how cultural irreverence is a necessary part of maintaining an author’s position in the literary canon—as each generation, with teenage logic, first mocks established authority and then lovingly refashions that authority in its own image.

Of course when we habitually celebrate Austen’s timelessness and eternal currency we risk losing touch with the original historical context of her work. My new book “Matters of Fact in Jane Austen: History, Location, and Celebrity” (Johns Hopkins, 2012) argues for Austen’s sustained interest in the celebrity culture of her own time by showing how she borrows famous names for her fictional characters or sets her stories in real-world locations with specific historical or “celebrity” associations.

The surnames Austen selected for her characters were as resonant with history in her own time as the name of Kennedy is today. By recapturing how names such as Fitzwilliam Darcy, Fanny Dashwood or Frederick Wentworth conjure up famous families, scandals or riches, I intend to restore more of Austen’s original daring and humor.

I do not know how long the current interest in Austen will last. I honestly believe that she’s starting to give Will Shakespeare a run for his money! But I do know that I never had this much fun (or this many students) when I was working on the novels of Samuel Richardson.

Janine Barchas is an associate professor of English.