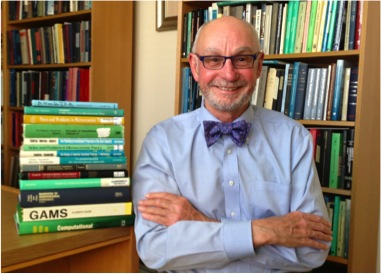

Recently the dean’s office asked liberal arts faculty to provide copies of the books they had authored over the years for a collection to be exhibited in the Gebauer Building. To comply with this request I began making a stack on my office desk.

My stack grew to 13 books, including two I had edited and two works translated into Japanese and French. The other nine were books I authored or co-authored over a 45-year career while teaching at Harvard and Texas, or on leave at Stanford and M.I.T.

The earliest book—from 1967—was one of the first economic studies to use computational methods to solve expansion planning models for large industries in which investment in production facilities were characterized by economies of scale. Though economies of scale are ubiquitous in major industries, these models could not be solved with analytical methods. However, they lent themselves well to solution methods for global optimization with algorithms such as mixed integer programming which I programmed on the “giant” M.I.T. mainframe computer of the day—the IBM 7094.

A few years later my colleague Sam Bowles and I published a textbook, Notes and Problems in Microeconomic Theory, which we developed for the first year graduate microeconomics course we taught at Harvard University.

A few years later my colleague Sam Bowles and I published a textbook, Notes and Problems in Microeconomic Theory, which we developed for the first year graduate microeconomics course we taught at Harvard University.

In 1970 I had the good fortune to be hired at The University of Texas at Austin by Dean John Silber a few short months before he was fired summarily by the regents. However, with tenure in hand, I decided to take a big risk and began work on a book that would take ten years to complete. At that time economic analysis and policy timing were tied to accounting methods and the annual budget cycle. However, some of my colleagues and I were moving toward a different approach that was based on the coming high tech world of feedback control applied to rapidly changing economic environments filled with uncertainties.

By the time I arrived at the Economics Department in Austin in the summer of 1970 I was ready to make a big investment in learning new mathematical and computational methods that could possible bring new technology to economics. The risk I took was to work on a single book for a 10-year period. One can only imagine the joy in the Kendrick household when that book, Stochastic Control for Economic Models, was accepted for publication by the McGraw-Hill Book Company.

However, the book had one drawback – it contained substantially more mathematics than words. In fact, the typist who converted my handwritten words and symbols into a manuscript asked: “This book has economics in the title … but is it really about economics?” In response to this question I later (1988) published a small book titled Feedback, which covered the same ground but used only words and no mathematical symbols. I hoped that this book would open the door for policy analysts and for a broader public to the coming world of high tech methods applied to economics.

Also in the 1980’s, I wrote a book with two colleagues about a new computer software system. This was done while I was serving as a consultant to the World Bank and helping to develop a system called GAMS that was a new departure from most of the software developed in that era. This software, whose principal creator was Alex Meeraus, was not a language for programming computer algorithms so much as a system for developing computer models of economic systems. As such it was used to create a great variety of models at the World Bank, in the financial community and in the defense industry. Later it was even used by Professor William Nordhaus of Yale University to create one of the earliest and most influential models of global warming.

The last book in the stack was developed over many years of teaching both undergraduates and graduate students about computational economics. In the early years of the 21st century I joined my former student, Ruben Mercado from Argentina, and my long time collaborator, Hans Amman from the Netherlands, to publish with the Princeton University Press one of the first textbooks in that field. At its publication, Computational Economics was characterized by Professor Alan Manne of Stanford University as “a pioneering textbook by the world leaders in the field.”

David Kendrick, 75, is a professor of economics at The University of Texas at Austin where he teaches a full load of undergraduate and graduate courses that are in great demand. His present research with George Shoukry and Hans Amman is a study of the potential improvements in macroeconomics stabilization which could be obtained by making fiscal policy changes quarterly rather than annually. Also, Kendrick was honored recently by the Society for Computational Economics when they created the Kendrick Award, which will be given every few years to a major contributor to the field of computational economics. In 2010 Kendrick was the first recipient of that award.