Neuroscientist embarks on a yearlong quest to study a single human brain, his own

Every Tuesday morning through November 2013, neuroscientist Russell Poldrack woke up, took off his headband-like sleep monitor and told it to wirelessly send data about his night’s sleep to a database.

Then he’d log in to a survey app on his computer and provide a subjective report on how well he had slept, whether he was sore and what his blood pressure and pulse rate were. He’d step on a scale, which would send his weight and body mass index to another database. Then he’d skip his usual paleo-style breakfast and head to his office, where he’s a professor of neuroscience and psychology and the director of the Imaging Research Center (IRC).

Poldrack followed this routine every Tuesday since the fall of 2012. It was part of his yearlong quest to study a single human brain (his own, as it happens) in more detail than a single brain has ever been studied before.

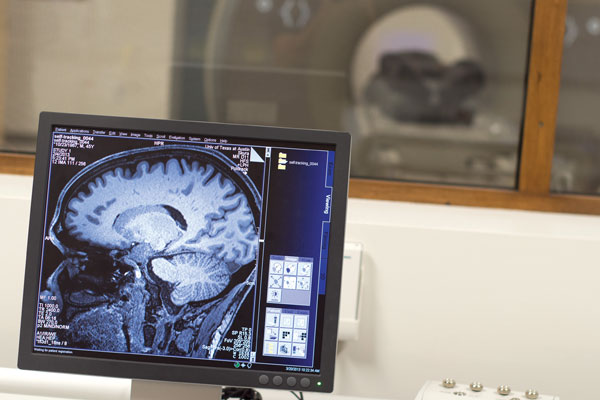

At 7:30 a.m. every Tuesday, he would head down to the basement of the building and lie down for 10 minutes while his brain was scanned by the IRC’s magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanner. Immediately after the scan he would fill out more surveys.

With that done he would walk over to the student health center, have some blood drawn and then drop off that blood sample at the university’s genome sequencing facility. The scientists there would analyze the blood for evidence of which of Poldrack’s genes were expressed that day.

If he exercised, he would wear a heart monitor, and the data would go into a database. On other days of the week, he might also submit to a high-resolution structural MRI, or perhaps work with his neuroscience colleague Alex Huk to perform high-resolution scans that can identify specific regions of his visual cortex.

On those Tuesday evenings Poldrack would do more surveys and reports. He noted, among other things, how much time he spent outdoors, the severity of his psoriasis during the day, how much alcohol he drank, what he ate, how stressed he was, how good his gut health was and how his mood fluctuated over the course of the day. Then he would strap his sleep monitor back on and go to bed.

Old-Fashioned Science

Not every day of Poldrack’s life, during the year of the “Russ-ome” Project, was as intensely tracked as on those Tuesdays. But every day he would fill out his surveys, wear his monitors and feed more data into a series of datasets that are so rich that he will need to use the supercomputers at the Texas Advanced Computing Center to make sense of it all.

“There’s a way in which it’s a very old-fashioned project,” says Poldrack. “There’s a long history of scientists doing experiments, sometimes crazy experiments, on themselves. It doesn’t happen much anymore, but in this case I couldn’t expect a volunteer to give up this much of their time. However, I’m obsessive enough that I thought I could actually pull if off, and I have the resources to do it.”

Poldrack hatched the idea, in part, after some fascinating conversations with Laurie Frick, an Austin-based artist whose work focuses on the “Quantified Self” movement—people who use monitors and sensors to track and then “hack” their lives.

Once all the data are in, toward the end of 2013, Poldrack will test some hypotheses and hopes to discover new ones by applying sophisticated data-mining techniques to the mountain of information he’s accumulating.

“Maybe we’ll see that particular gene networks move up and down in sync with a particular brain network,” he says. “And maybe there will be something happening metabolically, or in the subjective mood reports, that parallels this pattern. Then we can drill down.”

Discovery Science

Poldrack cautions that any pattern he discovers won’t have the scientific weight it would if he were doing a study of multiple subjects. But it will point the way forward to more refined hypotheses, which can be tested by more traditional means.

“Any finding that’s just from me could be a statistical fluke,” he says, “but the hope is that it will be meaningful as a driver of new hypotheses. It’s discovery science.”

“It’s about optimizing ourselves. That might mean getting smarter if you’re already smart, or losing weight effectively or figuring out how to best titrate your medicines if you have depression.”

Russell Poldrack

Robert Bilder, a professor of psychology and psychiatry at UCLA, sees Poldrack’s project as a bold, and potentially important, first step to filling in some of the big gaps in the field’s knowledge.

“Even in the cases where we’ve done the most scans of a single brain, we’re talking a few measurements separated by weeks, months or even years,” says Bilder, who is director of a major NIH-funded consortium dedicated to explore links between the human genome and complex brain functions. “As a result, we don’t even know what’s normal in terms of day-today variation. Russ’s project won’t tell us what’s normal, because it’s just one brain, but I think it’ll give us a sense of what’s possible. We’ll see the day-to-day fluctuation, see what kind of variability there is.”

Poldrack says the goal of the project, as of all his research, is to help us understand ourselves better so that we can exert more control over our lives.

“It’s about optimizing ourselves,” he says. “That might mean getting smarter if you’re already smart, or losing weight effectively or figuring out how to best titrate your medicines if you have depression,” he says. “It might mean using gene expression analyses, or even something as simple as an EEG, to monitor the efficacy of a treatment. We know almost nothing, right now, about how individuals change over longer time scales. We don’t know what’s possible.”