Think back to your favorite teacher. What stands out the most? Did he or she spark your enthusiasm for a subject that would otherwise seem dry and boring? Did that person treat you more like an equal than just an average student? There’s a reason why these teachers stand out from all the rest. They inspire students to do more, think critically, and let their imaginations soar to new heights.

Among the many faculty members in the College of Liberal Arts, two professors—Elizabeth Richmond-Garza and Héctor Domínguez Ruvalcaba—will likely stand out in their students’ memories long after graduation. Both are recent recipients of the prestigious 2013-14 President’s Associates Teaching Excellence Award. Read on to learn more about how they motivate students to learn in the classroom and beyond.

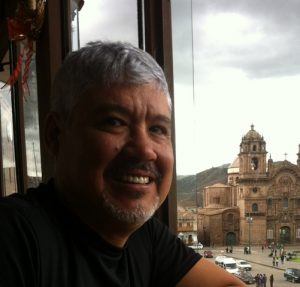

Héctor Domínguez Ruvalcaba, Associate Professor, Department of Spanish and Portuguese

Since beginning as a high school teacher in the 1980s, the question of how to motivate student learning was one of the favorite conversation subjects among my colleagues. “Students don’t like school,” was the hidden statement in all of those talks.

Since beginning as a high school teacher in the 1980s, the question of how to motivate student learning was one of the favorite conversation subjects among my colleagues. “Students don’t like school,” was the hidden statement in all of those talks.

Recently, I met one of my students from that time, now a successful professional, who reminded me of the first class I taught to him. He said I asked questions he didn’t know he could answer, and that he had the feeling students were happy in my class because I encouraged them to build knowledge by themselves through this simple and classic maieutic method.

For me, a class is an encounter with smart young minds that like to be listened to. Nothing is more rewarding than this dialogue with a group of future professionals who do not hesitate to tackle thorny issues such as gender and sexual violence, criminality or social inequity. The passion of the learning experience is grounded on the conviction that the classroom is a free space for thinking, that the problems we are addressing concern all of us, and that it is our moral responsibility to understand and imagine ways of intervention in those issues. I do not think we have to devise a complex strategy of motivation. Instead, I would say we need to work on those issues that are already part of students’ concerns.

Elizabeth Richmond-Garza, the University Distinguished Teaching Associate Professor, Department of English

In an 1857 poem, Charles Baudelaire invites a friend on an imaginary “voyage” to somewhere far away in time and space. In all my classes, I make the same invitation. Leaving home for Alexander Pushkin’s Russia, Oscar Wilde’s England, or Chinua Achebe’s Nigeria heightens your awareness. In an unfamiliar place, you must work interactively with your peers to understand it and yourself.

In an 1857 poem, Charles Baudelaire invites a friend on an imaginary “voyage” to somewhere far away in time and space. In all my classes, I make the same invitation. Leaving home for Alexander Pushkin’s Russia, Oscar Wilde’s England, or Chinua Achebe’s Nigeria heightens your awareness. In an unfamiliar place, you must work interactively with your peers to understand it and yourself.

Students will always read Hamlet, but I want it to come alive for them in London’s Globe Theatre or with Dr. Who playing the lead. Today’s literature teachers must combine honing writing and analytic skills with lively, personally rewarding engagement for all of our students. Hesitation with a foreign text translates into appreciation for the elsewhere and the elsewhen. It also prompts confident, imaginative interaction with the here and now.

Howard Gardner suggests that people possess “multiple intelligences.” In my courses, students inhabit a dynamic, interdisciplinary and multimedia world. Students of Virginia Woolf need to stroll down a virtual London street. Kevin Spacey’s midlife crisis in American Beauty echoes Dante’s in Inferno. Critiquing Disney’s imagery allows students to appreciate the original 1001 Nights. Music, architecture, painting, film and computer games transform an ordinary room into a gateway to another time and place.

I never receive a batch of uniform essays or give a lecture in which I speak uninterrupted by questions, or my live Twitter feed, for more than ten minutes. Literature offers students a safe, fictional laboratory—a virtual environment—in which to test their own responses to complex, troubling situations, knowing that they will not have to suffer the actual consequences endured by their imaginary avatars. My goal is to allow students to feel at home in a world of challenging texts and ideas, not despite but because of their intellectual or personal point of origin.