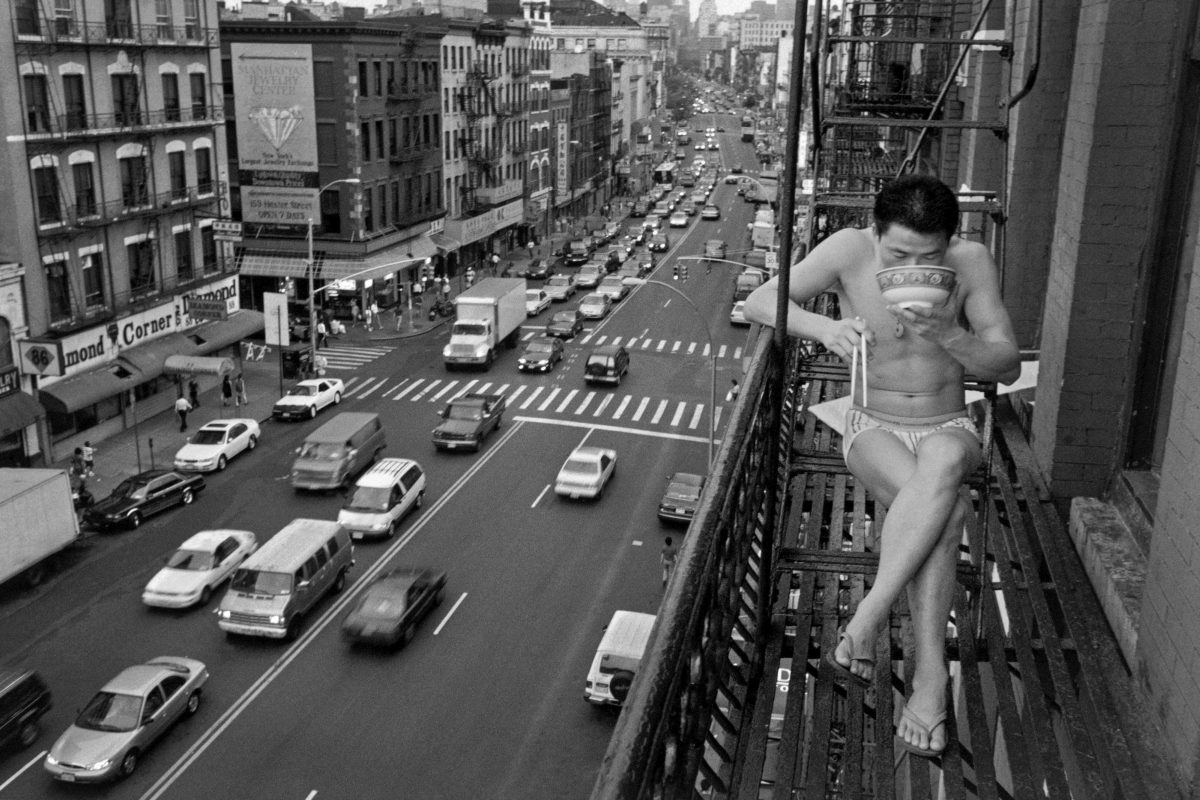

High above a blur of cars on a congested street in Lower Manhattan, a Chinese man sits atop a tiny fire escape sipping a bowl of noodles.

Surrounded by a concrete jungle of asphalt and high-rise buildings, the man is far from isolation. Yet somehow he appears to be very much alone and out of place.

This powerful portrayal of modern immigrant life —the cramped living space, the alienation, the absence of color and wide-open spaces – exquisitely captures the parallels between inward struggles and the outside world.

This 1996 photograph from Chien-Chi Chang’s China Town project is one of many iconic photographs in the massive Magnum Photos archive that evoke a sense of wonder and mystery about the world around us. While many of these prints are now valuable art commodities, they were originally intended for reproduction in publications around the world, says Steven Hoelscher, professor of American studies and geography at UT Austin.

In Reading Magnum: A Visual Archive of the Modern World—which Photo Magazine recently named “Book of the Year,”—Hoelscher and a team of seven international scholars offer an in-depth account of the Magnum photographs as they are shuffled around from one publication to another and viewed in a wide range of contexts.

“The vast majority of these photographs were initially intended to be published, not to be hanging on a gallery wall,” says Hoelscher, who has an appointment as an academic curator of photography at the Harry Ransom Center, which now houses the Magnum collection. “Tracing the life of the photograph is important. You learn more about the intentions of the photographer, the circumstances surrounding their reception, and larger social-cultural impact.”

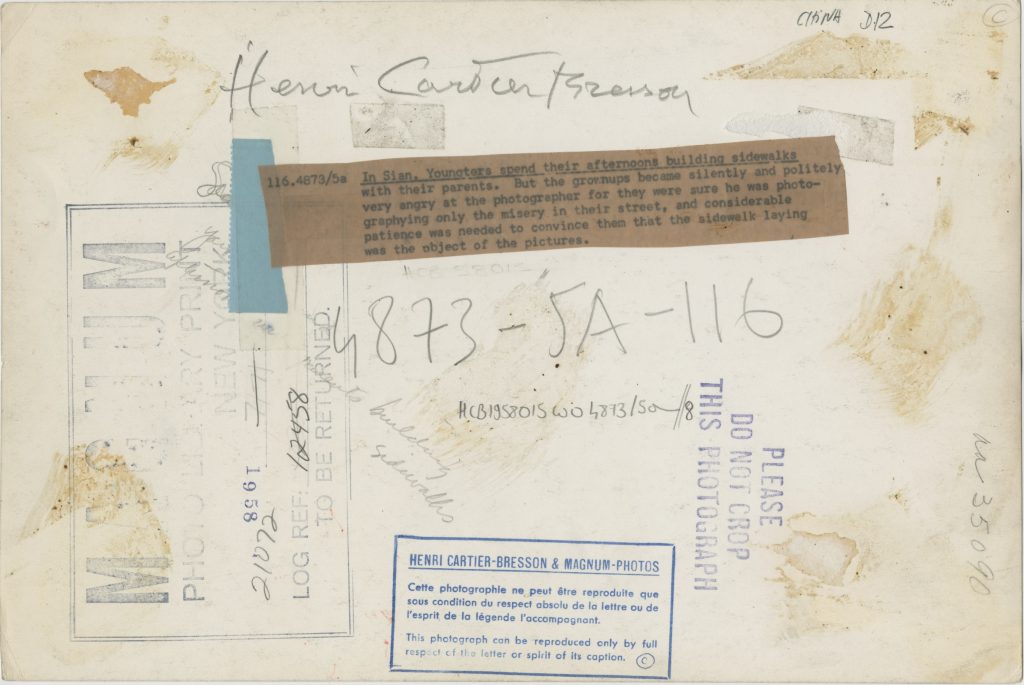

Founded in 1947 as a cooperative, Magnum Photos was the first photo agency to be owned and managed by photographers. For the first time, these visual authors were able to control the use of their photos in magazines and newspapers. On the backs of the photographs, they printed a collage of serial numbers, stamps, codes and various other markings to ensure that their works were properly displayed.

Each chapter in Reading Magnum is punctuated with a “Note from the Archive,” a behind-the-scenes look into the photographers’ aesthetic visions in which Hoelscher decodes the smudged clusters of handwritten metadata.

Now as images on paper are being replaced by images on a screen, it is important to keep a material record of the making and dissemination of print photography, Hoelscher says. Something as simple as a photographer’s signature can tell us a lot about the direction of photography back in the 1950s, before prints were considered to be valuable art commodities.

A notable marking is Magnum co-founder Henri Cartier-Bresson’s signature on the back of one of his photographs, says Hoelscher as he flips the book open and points to an enlarged image emblazoned on the inside back cover.

“This is quite unique because back in 1958 photographers didn’t think of prints like this as pieces of art,” Hoelscher says. “From his caption, you can tell that Henri Cartier-Bresson was more interested in describing his interaction with the people he photographed. Once it acquired value as a ‘vintage’ print, the photographer added further value by signing it.”

Flipping through the glossy pages, it’s easy to get lost in the traumatic scenes of warzones, the whimsical landscapes, the vintage slices of Americana. These stunning visuals are featured in the “Portfolio” sections throughout the book, illuminating the themes of the chapters: war and conflict, portraiture, and the importance of geography and culture.

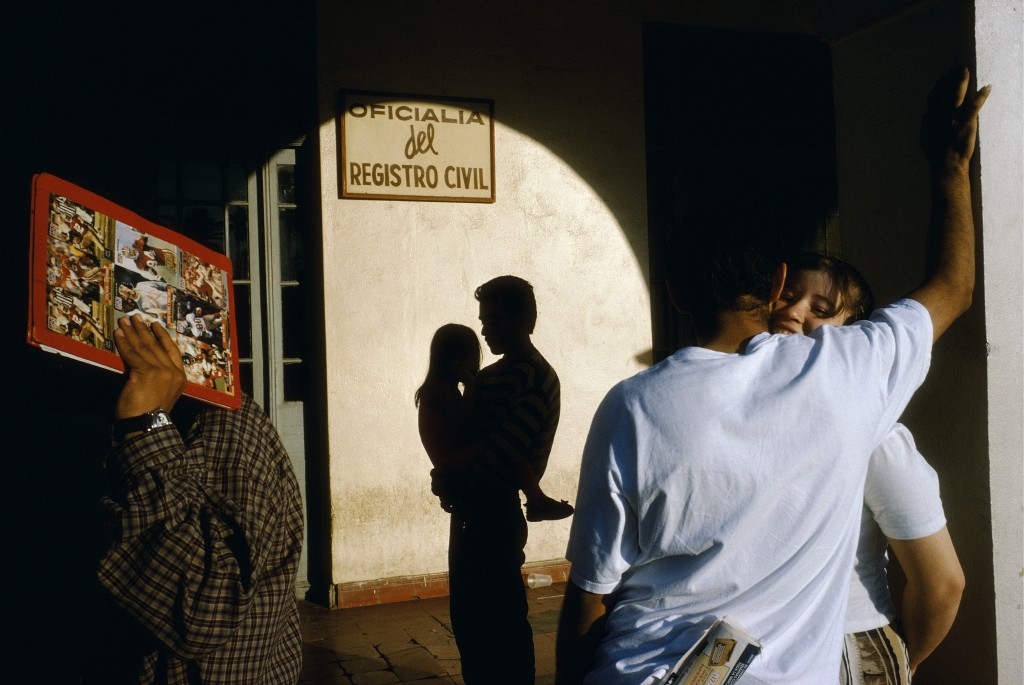

When asked to highlight a particularly striking image, Hoelscher points to Alex Webb’s 1996 photo Nuevo Laredo, Mexico. Read on to learn more about his take on the photographer’s artistic depiction of the complex nature of the U.S./Mexico border.

Photographs of borders and edges of societies—places where cultures sometime merge and sometimes clash, and where political ambiguity and uncertainty dominate—are common throughout the Magnum archive. One finds many examples of the borders between Palestinians and Israelis, between rich and poor in American cities, between superpowers during the Cold War.

One interesting example is found in Alex Webb’s 1996 photograph of Nuevo Laredo, Mexico. Without being set up or orchestrated—Webb says that his photographs are “a response to the world as-is”—it achieves a perfect aesthetic balance in all dimensions. But it’s much more than just a beautiful picture: it’s a complex photograph perfectly suited to the complex nature of the border, one full of exquisite contradictions and questions. Words in Spanish and pictures of American football players; a place where social interaction and isolation coexist; an acceptance of an outsider’s camera and an attempt to hide from it: cultural mixture and cultural dissonance go hand-in-hand.

Webb’s first travels to the region, in 1975, focused on the world of illegal border crossings. This initial interest soon expanded into the “whole feel of the border.” He observed that, at the border, there is a perpetual transience—of people and commodities—in both directions, which creates a unique sense of place. Although Webb has taken many photographs of the border patrol, his borderland photographic project has multiplied dramatically to include the cultural, economic, political, and spiritual crossings. Webb’s description of the way in which different cultures come together at the border could almost be taken for a description of the visual components of this photograph: “sometimes they fuse, sometimes they remain separate, but meld in interesting ways, almost in layers.”