Strategies for Improving Education in America

Few dispute the value of education, but discussions about how our nation should improve it are becoming more intense and polarized. Of all the competing arguments—more technology, smaller classrooms, improved teacher training, universal pre-kindergarten—most people would agree that America’s education system needs to improve, and soon.

According to recent standardized test results from the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), U.S. schools remain stagnant, while other countries race ahead. Findings show that our nation’s 15-year-olds are in the middle of the global pack in reading and science while lagging in math.

That pattern has not fluctuated much since the PISA test was first given in 2000. While some believe these results are a wake-up call for policymakers and education officials, others argue that Americans haven’t topped international test rankings since the 1960s, but still rank high in innovation.

Compared to its own history, the U.S. education system may be treading water just fine. But compared to the rest of the world, it needs work—and quickly, says Jeremi Suri, professor in the Department of History and the LBJ School of Public Affairs.

“The quality of education is becoming more and more important in terms of one’s ability to be actively engaged and contribute to business and intellectual life around the world.”

Jeremi Suri

Now is the time for schools to focus on preparing students for an increasingly competitive, interconnected global economy, Suri says. Most jobs will go to the most capable individuals, regardless of geography. Without quality education, U.S. students are at risk of losing out to their international competitors.

“The quality of education is becoming more and more important in terms of one’s ability to be actively engaged and contribute to business and intellectual life around the world,” Suri says. “It’s not just a degree, it’s a set of skills you need to communicate. And as the world is becoming more competitive, education is more of a defining measure of whether you’re included or excluded.”

Several leading scholars in the College of Liberal Arts are exploring new ways to bring the United States back to the top of the international podium—from school readiness, to teacher training, to re-defining parental involvement.

The Case for Early Education

School readiness—the skills children bring with them to kindergarten—is a particular cause for concern in our nation’s political discourse. In his 2014 State of the Union address, President Barack Obama emphasized the need to “make high-quality preschool available to every single child in America,” rallying support among advocates who have long argued that universal pre-kindergarten is an investment in society that will ultimately pay out in high dividends. To quote Obama, “Every dollar we invest in high-quality early education can save more than seven dollars later on.”

Preschool children are already enhancing their language and literacy development before setting foot in kindergarten, says Rob Crosnoe, professor of sociology and Population Research Center associate. With these skills, they are well ahead of the learning curve, leaving their underprivileged classmates behind.

Yet the children who need these language skills the most are less likely to attend preschools. According to a 2013 Kids Count report from the Annie E. Casey Foundation, U.S. Hispanic children have the lowest preschool attendance rate compared to all other racial groups.

However, more first-generation immigrant children are outperforming their U.S-born classmates in secondary school, Crosnoe says. This phenomenon, coined by social scientists as the “immigrant paradox,” appears to hold better for some age ranges than others.

In a recent study, Crosnoe found this pattern of academic success isn’t as consistent among young children, who are much less likely than their peers from U.S.-born families to get a formal preschool education. The biggest disadvantage, Crosnoe says, is the language barrier.

“When children of immigrant parents start their first day in kindergarten, they’re already showing disparities in social class and race,” Crosnoe says. “And once they get into the school system, those small yet significant disparities tend to grow, leading to dropout in high school and college. That’s why it brings greater return to investment if you can eliminate those differences early on.”

Crosnoe says the higher-achieving first-generation students do better than later, more Americanized generations—and that happens across all racial and ethnic groups. Over time, as they assimilate with their classmates, they tend to lose their idealistic goals of achieving the “American dream,” a value that their parents often teach to them at a very young age.

“As children in immigrant families get older, they become more acculturated and lose their positive attitude toward parents and teachers over time,” Crosnoe says. “They become more adjusted to typical teenage life and that’s when their grades begin to slip.”

In addition to quality preschools, Crosnoe sees the need for more programs, such as English as a Second Language (ESL) classes, that can help demystify the educational process for parents and students. He believes these structural changes could go a long way in increasing their economic and social contributions to American society.

Hands Off the Homework

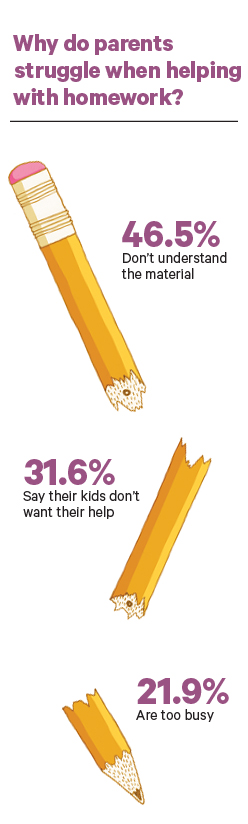

There’s no underestimating the parents’ value in their child’s education. Many go above and beyond to give their children an academic edge by volunteering in the classroom, coaching extracurricular activities or devoting hours of their time to daily homework tutorials. These all seem like effective strategies for putting children on the road to success, yet Keith Robinson, assistant professor of sociology and Population Research Center associate, has found evidence to the contrary.

In one of the most thorough scientific investigations to date of how parents contribute to the academic performance of K-12 children, Robinson and Angel Harris, a sociology professor at Duke University, examined 63 different forms of parental involvement at home and at school. Surprisingly, they found almost all of the observed activities are mostly inconsequential—sometimes even detrimental.

Among the findings detailed in their new book, The Broken Compass, one particular problem area is parents helping with homework. Despite their best intentions, many parents are ill-equipped to handle the material their kids are studying now, Robinson says.

But this doesn’t mean that parents need to take a laissez-faire approach to their children’s schooling. In the study, the researchers found one form of parental involvement that produced positive results across the board: Talking to their children about future academic goals.

So rather than taking a hands-on approach to schoolwork and extracurricular activities, Robinson suggests that parents should drive the message home that good grades lead to a promising future.

Although the researchers found more similarities than differences in parental involvement across all racial and economic groups, they found Asian parents are most successful at communicating the value of school.

“We found Korean, Japanese and Chinese families are hardly involved in most of the activities we measured,” Robinson says. “This is really interesting because these ‘model minority’ parents have the most successful children. Although they’re not partaking in the conventional behaviors, they appear to be effectively communicating the value of school.”

Robinson stresses the fact that parents matter—in a very big way. He believes now is the time to pinpoint how they can best help their children in new, unconventional ways. Although his research has only scratched the surface of parent-child learning, he believes that with the right interventions, parents—from all walks of life—will become much more effective in strategizing their children’s academic pursuits.

“We need to look at ourselves, at our parents, at our schools to figure out how parents matter,” Robinson says. “My hope is that schools will be able to work with parents to create a seamless educational environment. We need more discussions with both parents and educators about what works for which types of children—and at what stage in their education.”

Raising the Bar

A growing body of research is showing that positive encouragement can go a long way in pushing children to meet their true academic potential. Sometimes just a teacher’s remark can prompt a student to push harder, make better grades and envision a better future.

According to new research conducted by David Yeager, assistant professor of psychology, the key to unlocking student success may lie within empowering messages. Rather than telling a student, “Great job—you’re smart!” a teacher could unlock motivation by emphasizing that learning and growth are more important than natural ability.

“Teaching students that intelligence can be developed—that like a muscle it grows with hard work and good strategies—can help them view struggles in school not as a threat but as an opportunity to grow and learn,” Yeager says.

Yeager says his findings have important implications for teachers across the nation who must help students meet new Common Core standards. Adopted by 45 states, the standards set “college readiness” goals for what students should learn in reading and math from one year to the next. The standards will be fully implemented by the 2014-15 academic year.

Recommended Reading

The Broken Compass

Parental Involvment with Children’s Education

Harvard University Press, Jan. 2014

By Keith Robinson, assistant professor, Department of Sociology, Center for African and African American Studies and Population Research Center associate; and Angel L. Harris

Fitting In, Standing Out:

Navigating the Social Challenges

of High School to Get an Education

Cambridge University Press, March 2011

By Robert Crosnoe, professor, Department of Sociology and Population Research Center associate

“When districts adopt the new higher standards, more students will fail to meet them,” Yeager says. “How will they respond? Will they be resilient, and keep working? Or give up? Psychology has a lot to say about making sure that students stay in the game as standards rise.”

Students have a tendency to think struggling in school means they’re just plain dumb, Yeager says. But when teachers counteract this thinking, they become more resilient.

In a recent study, Yeager found students significantly improved when they received messages from their teachers that conveyed higher standards and genuine beliefs in their abilities. Sentiments such as, “This work will be hard, but remember I wouldn’t ask you to do it if I didn’t believe you could grow your ability and reach a higher standard,” dramatically accelerated all students’ academic performance.

“These seemingly small messages can help repair mistrust that sometimes occurs when minority students are criticized by majority group teachers,” Yeager says. “When students trust their teachers, they can use critical feedback to grow and improve.”

In a forthcoming study, Yeager and his colleague Greg Walton, a psychology professor at Stanford University, delivered positive messages about growth and potential to more than 10,000 freshmen at several U.S. universities. They found one-time exposures to these messages in the summer before the fall semester resulted in positive effects—in some cases reducing achievement gaps by 50 percent.

These findings have important implications for educators, yet Yeager stresses a word of caution when applying positive interventions in everyday classrooms.

“In an effort to keep students from feeling ‘dumb,’ teachers tell students they are ‘smart,’” Yeager says. “Or they praise them for things that anyone can do. But this can backfire. It makes students focus on ‘smartness’ or it can communicate low expectations.”

Yeager says both psychological and structural interventions could lead to significant improvements in American schools.

“Strategies that address problematic student beliefs complement—but do not replace—traditional educational reforms,” Yeager says. “Psychological interventions don’t teach students academic content or skills, restructure schools or improve teaching. Instead they allow students to seize opportunities to learn.”

Testing, Testing

Engaging students to learn is no easy task for public school teachers who face the pressures of revolving their lessons around standardized testing, or what is called “teaching to the test.”

Although these tests serve a purpose in school accountability, it’s time to rethink U.S. education standards that stress rote learning and largely ignore critical thinking, says Suri.

“I’m not against testing, but it takes the creativity out of teaching,” Suri says. “And oftentimes the material they’re teaching is boring, uninspiring and sometimes even wrong. It’s sort of like requiring actors to follow the same formula in all of their movies. You’ll stop watching because they’re boring and predictable.”

While basing classroom instructions on how to fill in all the right bubbles on a multiple-choice test, teachers are missing important opportunities to ignite a thirst for knowledge, Suri says.

“I come from a very modest immigrant family and attended public schools in New York City,” Suri says. “I will always be thankful for the teachers who gave me opportunities—not just to become a better student— but to understand the importance of lifelong learning. I’m very grateful, and now I want to give something back.”

To pay it forward, Suri brings a group of top public school teachers from across the nation to UT Austin for a weeklong professional development seminar. Sponsored by the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History—one of the leading educational foundations in the country—the goal is to help teachers gather new research and breathe new life into their history lessons.

With a focus on the history of U.S. foreign policy, the seminars include readings and lectures by distinguished professors, as well as tours of archives and book collections in world-class libraries and museums. Suri says this is one of the many steps that universities should take to extend a wealth of research materials to public school educators.

“Teachers touch the lives of so many students,” Suri says. “It’s our obligation to provide the materials to prepare students and also inspire them. I want teachers to know that we care about what they’re doing and to inspire them to work hard. I want them to pass this message on to their students.”

Joan Neuberger, professor of history, is all too familiar with the pitfalls of “teaching to the test.” She often meets with history teachers to gather information for the History Department’s public history website, Not Even Past.

Neuberger says one of the biggest challenges for teachers is staying current on the best and most recent research while facing pressures to prepare students for standardized tests in overcrowded classes every day.

With this in mind, Neuberger and her colleagues provide a wealth of new, reliable history research to the public on Not Even Past. It offers free materials—from videos with top history scholars, to faculty book recommendations, to articles about overlooked corners of history.

“Because a fundamental part of our job as university professors is to produce new research and know the literature in our fields, we’re in a position to provide primary and secondary school teachers with resources in a format that is readily accessible,” Neuberger says. “I think it is especially important to counter misinformation and misguided policies that reach the public sphere.”

Specifically produced with secondary school teachers and students in mind, the website’s 15-Minute History podcast series features interviews with leading historians and graduate students about various topics in U.S. and world history. Complete with supplemental materials, the episodes are aligned with state and national educational standards.

“Our goal is to make the work we do on complex and even contradictory events accessible to everyone,” says Neuberger, who co-created the series with Christopher Rose, outreach director for the Center for Middle Eastern Studies. “We must be doing something right, since 15-Minute History has been ranked the No. 1 collection on all of iTunesU since January 21.”

By providing much-needed learning resources, Suri and Neuberger aim to help educators succeed. Teachers play a critical role in helping our young people—the next generation of scholars, thought leaders, workers and parents—understand that they can make a difference in building a better world, Suri says.

“Education is about bringing the American dream into the classroom,” Suri says. “You want a poor immigrant child to imagine him or herself as the next president of the United States, or as a CEO. They have to dream it—and history is a great way to do that because it tells the story about the people who lived the reality of it.”