Many people dream of getting rich, of leaving the drudgery of work for a life of financial freedom. Daniel Fridman, an assistant professor of sociology and the Teresa Lozano Long Institute of Latin American Studies, investigated how groups of people in New York City and his native Buenos Aires attempt to take control of their financial destiny by reading books, attending seminars and playing a game called Cashflow. Fridman is interested in how people have responded to changing economic realities such as loss of job security, diminished income in retirement and a general weakening of the social safety net.

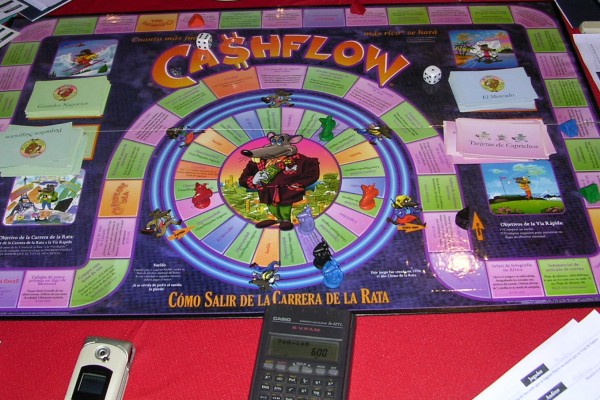

Over the course of two years, Fridman conducted ethnographic fieldwork among groups of people who play Cashflow, a game created by Robert Kiyosaki, personal finance guru and author of the Rich Dad, Poor Dad series of books. With translations into over 50 languages, Kiyosaki’s books are advertised as containing tools that anyone can use to attain financial freedom. Kiyosaki advocates that instead of working to earn money, people should develop financial intelligence so that their money will work for them. People who play Cashflow do so in hopes that the game will help them gain the technical tools necessary to get out of the “rat race,” a life in which one must always work in order to earn money, and onto the path to financial freedom, where “passive income” is earned through investment in real estate or multi-level marketing businesses.

Fridman’s subjects, both in New York and Buenos Aires, come from all walks of life. Some have advanced degrees; others only a high school diploma. Some, not all, are successful in their chosen profession. What they have in common is the desire to change the way they interact with the economy, to arm themselves with the tools and knowledge they believe will lead to financial freedom. But even deeper than that, through their reading of books and attendance at seminars, they are challenging what they learned about money as children—in their families, in school, and among their peers. They are challenging their assumptions about who has money, who doesn’t, and why.

As Fridman points out, the fact that so many people can entertain the possibility of getting rich without working is a relatively recent phenomenon. After all, he says the “recommendation of eventually quitting one’s job in favor of investing is only credible under economic conditions that emerged in the last quarter of the 20th century.”

Fridman’s point of departure is not to ask whether reading books, playing Cashflow, and attending seminars actually “works.” Ultimately, he is examining a response to the economic shifts of the last three decades whereby some people attempt to transform themselves from within—in some cases, freeing themselves to try and fail—in order to attain lasting financial freedom.