It was a chance discovery of a 1782 broadside—advertising a play performed in Baltimore about the Prophet Muhammad—that piqued the curiosity of Denise Spellberg, professor of history and Middle Eastern Studies. She wondered, why did Americans perform this play during the Revolutionary War? More importantly, the historian of Islamic civilization asked, what did early Americans know about Islam, and did their purview for political equality and citizenship include Muslims?

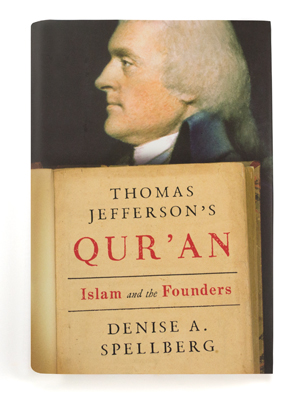

Over the next eight years, Spellberg uncovered founding debates about the inclusion of Islam, as an American religion, and declarations by a handful of pivotal founders who defended the civil rights of future Muslim citizens. Among this then radical cohort were Thomas Jefferson, George Washington and James Madison, as well as others who were less well known. The results of her research became the core of her book, Thomas Jefferson’s Qur’an: Islam and the Founders, published by Knopf last year, and praised by The New York Times as “fascinating” and “revelatory.”

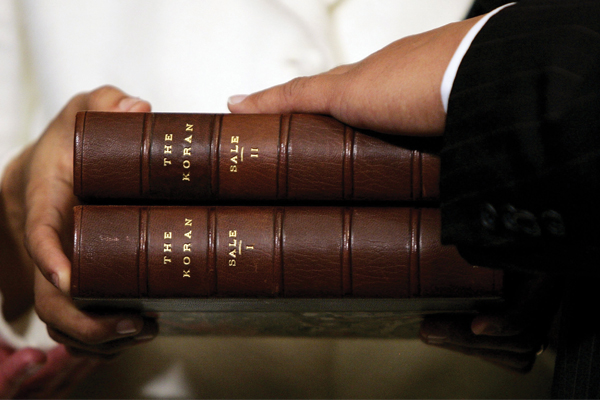

The book’s title references Thomas Jefferson’s Qur’an, now held in the Library of Congress. Jefferson bought his Qur’an in 1765, 11 years before writing the Declaration of Independence. At the time, the 22-year-old law student probably perceived the sacred text as a book of law, a perspective common among Christians since the 12th century, when the Qur’an had first been translated into Latin. Jefferson, a bibliophile, had purchased books of British law at the time, but left only his initials in the Islamic sacred text, the first translated directly from Arabic to English.

“As a historian, I was frustrated and disappointed that for a man who took assiduous notes on much of what he was reading in the 1760s and 1770s, we have none of those notes based on his immediate reaction to the Qur’an,” Spellberg says. She adds that Jefferson lost all of his books and papers in a fire five years later, which may explain why his response did not survive, and prompts her to wonder if he purchased the Qur’an twice, a possibility that cannot be proved.

Spellberg explains that Jefferson, early on, criticized Islam in his 1776 debate notes as a religion that repressed what he termed “free enquiry,” a critique he also levelled against Catholicism. While the historian says that Jefferson received this mistaken precedent about Islam from the French philosopher Voltaire, she adds that such an assertion worked well politically for his exclusively Protestant audience in the Virginia House of Delegates. All Jefferson’s Protestant listeners would have held quite negative views of both faiths—and Judaism—at the time.

However, in that same year—just a few months after writing the Declaration of Independence—Jefferson recorded a critical passage from one of his intellectual heroes, the English philosopher John Locke: “[N] either pagan nor Mahometan [Muslim] nor Jew ought to be excluded from the civil rights of the commonwealth because of his religion.”

“So, we can see that he had a dual-edged view,” Spellberg says. “On the one hand, he had little that was positive to say about Islam at this early stage. On the other hand, what is interesting is that he could separate the idea of Muslims as future citizens of the United States, and he could conceive of their civil rights along with all other religious believers.”

Another crucial discovery for Spellberg was the detailed transcript of a 1788 debate about the ratification of the U.S. Constitution in North Carolina, which captures the reaction of Protestant delegates to the abolition of a religious test for federal officials, including the president, found in Article VI, section 3. “Early in the debate, it comes up that if there is no religious test, then maybe non-Protestants will get power, and among the people most feared on that day were Catholics, Jews and Muslims,” Spellberg says. “And so that’s the first time we see the question of a Muslim president arise in American political debate. And what’s particularly interesting is that the Federalists in support of the Constitution that day make a theoretical argument that says you can’t exclude anyone from political office, including Muslims.”

“[Jefferson] perceived a future state of inclusion for Muslims at a time then, as now, when there were many who were fearful of Islam and people from the Middle East.”

Denise Spellberg

Spellberg points out that in such debates, Jefferson and his contemporaries were thinking about Muslims in America in a completely abstract and theoretical sense, as they mistakenly believed there were no Muslims yet in the United States.

However, historians believe that by Jefferson’s time, there would have been Muslim slaves in the thousands, if not the tens of thousands, because in North America some estimate that up to 15 percent of slaves from West Africa were followers of Islam. In fact, records show that George Washington owned at least two, and possibly four, Muslim slaves on his plantation. Records are not definitive on Jefferson, also a slave owner, though Spellberg notes it was certainly possible that he owned slaves of Muslim origin as well.

Spellberg says the tragic irony is that race and slavery meant the Muslims who were already in America at the time could never have exercised the civil rights that Jefferson and Washington envisioned for them in the future.

“Thomas Jefferson was a complicated character, but he was a visionary, and he perceived a future state of inclusion for Muslims at a time then, as now, when there were many who were fearful of Islam and people from the Middle East,” Spellberg says. “At the time, there were people who were fearful of the threat of Catholics and Catholicism, but he never operated from fear of any religion or any group of people. He was able really, in that sense, to separate this notion of what his country should be, universally inclusive of all its citizens, regardless of religion. And it’s the breadth of that vision that still takes my breath away.”