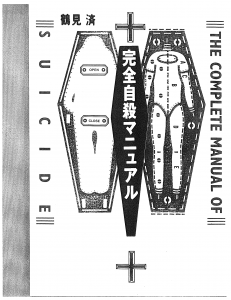

Japanese artists have scripted suicide into their work, sometimes marking destinations for contemplating, committing and mourning suicide, morphing modern Japan into what some consider a “suicide nation.”

Kirsten Cather, an associate professor in the Department of Asian Studies, looks to 20th century Japan to answer the question: What happens when people inscribe their suicides in art – on the literary page, theatre stage, film screen, or manga panel – and onto the landscape?

“It’s been scripted in both art and the landscape,” Cather said. “Most people tend to ask why someone committed suicide. I want to know what traces they left behind, and why they framed their messages the way they did.”

In Japan, suicide numbers are high at about 19 deaths per 100,000 people annually, Cather explained. Many artists have left traces of their suicide behind in their work, influencing others to contemplate and even imitate the act.

“Often, one spectacular suicide sets off a chain of others, inspiring an act or marking a suicide destination in the traces left behind,” Cather said.

Today’s poetic suicide spot is a forest outside of Tokyo at the base of Mount Fuji, Aokigahara, home to hundreds of confirmed suicides since the 1960s and the second only to the Golden Gate Bridge as the world’s most popular place for suicide. The site became popularized in part by a 1960 pulp fiction novel, Tower of Waves (Nami no tō), that depicted its forlorn female protagonist wandering into the dense forest to die.

This isn’t the first time a landmark has been marked as a suicide spot. Other historically “hot spots” for suicide included Kegon Falls, in 1903, and Mount Mihara volcano, in the 1930s. Both spots, Cather said, were romanticized in literature and art.

“What is the relationship between writing and suicide? And, what are the ethics of producing and consuming this kind of art?” Cather asks in her research.

She is compiling her research in a new book, Scripting Suicide in Modern Japan.

“I hope it opens up a discussion about suicide,” Cather said. “Unfortunately, most people have been touched by suicide, but we don’t have very good tools to talk about it. By looking at a culture and country that is distant and distinct from our own, we can think about how it relates to our own culture and concepts.”

Cather’s work was supported by a Humanities Research Award, a three-year $15,000 research grant created by the Dean of the College of Liberal Arts. She presented her findings at this year’s Humanities Research Award Symposium.