For the estimated 350 million people worldwide who suffer from depression, the health consequences go far beyond “feeling down.” In fact, it is a leading cause of disability worldwide, according to the World Health Organization.

Unfortunately, the vast majority of people with symptoms of depression will never receive treatment, and for those diagnosed with major depression, up to half will not get better after their first treatment.

“Wouldn’t it be great if there was a way to identify who was going to respond to your treatment before you gave the treatment?” asks Christopher Beevers, psychology professor and director of the Institute for Mental Health Research (IMHR) at The University of Texas at Austin.

That’s the big question he’s trying to answer at the IMHR. By taking a translational research approach — applying basic research to improve health and well-being — the IMHR is using discoveries from genetics, cognitive neuroscience and animal research to better understand mental illness and improve treatments.

Beevers says one of the biggest challenges in the field of depression research is that depression comes in many forms. Researchers at UT Austin are exploring some of the best ways to personalize treatments and some of the mechanisms that cause and maintain depression.

“You can’t just take a group of depressed people and assume that they are all the same and that they’ll respond similarly to whatever intervention you give them,” Beevers says. “There are some people who will get better on their own and some people who will remain depressed for months, even years, without intervention.

“So one of the challenges is to identify the people who are going to recover on their own and who needs interventions,” he adds. “We are still just in the early days of trying to figure this out.”

Genetic Breakthroughs

Beevers says one of the biggest breakthroughs for depression research has been the rapid advancements made in the field of genetics. When the IMHR was established in 2012, researchers were looking at a single variance within a single gene. Now the IMHR researchers are able to look at a million variations.

“We try to pick out the ones that are more likely to give us some signal,” Beevers says. “It’s amazing how quickly that area has developed and continues to develop. We can look at genetics much more comprehensively than we could even five or six years ago.”

Through the use of therapygenetics, the IMHR researchers are trying to identify who might best respond to a particular form of treatment called cognitive behavior therapy. The goal is to develop algorithms to identify people who would best respond to this type of treatment, so that they don’t have to waste time with trial and error. This can save time and money and alleviate unneeded suffering.

The IMHR brings together an interdisciplinary team including clinical psychologists, cognitive neuroscientists, geneticists and statisticians. It is supported in part by the Dianne and Jerry Grammer Excellence Fund for Mental Health Research and the Judith M. Craig, Ph.D. Excellence Endowment for Mental Health Research, which helps attract some of the top research talent in the world.

Rahel Pearson, a graduate student at the IMHR from the Netherlands, works on a research team that recently demonstrated that people with a certain genetic risk factor are less likely to exhibit negative attentional bias under conditions of social support.

There is a substantial amount of literature suggesting that certain people are more likely to experience negative outcomes because of genetic factors. Only recently has there been an increased focus on the interaction between positive environments and genes.

She says some people may be more sensitive to environmental change “for better and for worse.” Susceptible people (e.g., those with certain genes) — relative to others — are more adversely affected by negative environments and are more beneficially affected by positive ones.

“Since treatment for depression can be seen as a positive environmental change, this might mean that more susceptible individuals would do better in treatment,” Pearson says. “Knowing which people are likely to benefit most from treatment allows us to better target scarce resources.”

She says that until now clinical psychologists have been very focused on researching negative environments because they are mostly interested in the outcome that inhibits a person from adjusting to particular situations, but it’s a narrow spectrum.

“I think that looking at positive environments can help us understand why some people are more likely to develop maladaptive outcomes, and how we can promote resilience and recovery,” she says.

Pearson would like to continue to focus her research on environmental factors that are relevant for depression. In the future, she hopes to further examine how these environments — either alone or in interaction with genetic factors — are implicated in depression.

“We already know that stress is bad, and when you encounter environmental stressors, you are more likely to become depressed,” she says. “However, it seems unlikely that all environmental stressors are created equally.”

Why Do People Remain Depressed?

Stressors that involve significant loss are particularly potent predictors of depression, such as becoming unemployed or divorced or losing a loved one. A loss may fuel depression, leading a person to socially withdraw, therefore maintaining his or her negative mood. It’s a negative loop that Beevers and his team of researchers are working to reverse.

“All of these things seem to precipitate depression, and then if you have this tendency to focus on the negative aspects of that loss, then that’s likely to fuel your depression and maintain it over time,” Beevers says. “How they respond to these events and what they focus on can lead to dramatically different outcomes.”

During the past 15 years of Beevers’ career, he’s done extensive psychopathology work to identify the factors — cognitive biases or processes — that maintain depression. His research explores possible ways people are thinking or interpreting events around them or their tendencies to recall things that are keeping them depressed.

For example, through the use of eye tracking technology, he and a team of researchers found that it took depressed people significantly longer to shift their attention away from negative information than a nondepressed person would take. That bias can be a predictor for depression and for being depressed longer.

“Rather than giving a nonspecific therapy, we are really trying to target the mechanisms that in prior work we’ve shown to be associated with depression and maintaining depression,” Beevers says.

He says this insight helps to focus the research. By manipulating those mechanisms through experimentation, he might determine which ones help people get better.

“Eventually, we’ll get to the point where we can do an assessment, get a sense of the biases they have and then pick a treatment based on that assessment,” Beevers says. “That’s where this is all headed … Up to this point, we haven’t been able to do this with pharmaceutical therapies, behavior treatments, really any form of treatment for mental health issues.”

Decision-making

The IMHR has done a number of studies showing that depressed people are less able to learn from positive information such as rewards in the environment. When depressed people make a good decision, they pay less attention to it and are less influenced by it in their future decision-making. Conversely, they are more sensitive to receiving punishments when they make mistakes.

“They are really hyper-focused when they make a mistake and adjust their decision-making much more dramatically,” Beevers says. “So they have this tendency to really pay attention to the negative information and maybe overcorrect when they make mistakes and not pay enough attention to positive information.”

“You can’t just take a group of depressed people and assume that they are all the same and that they’ll respond similarly to whatever intervention you give them.”

Chris Beevers

Based on work with healthy individuals to improve executive function — that is, the cognitive control over how people think — the IMHR researchers designed brain-training exercises. For a month, study participants were asked to spend 15 minutes every day completing a simple math problem. They were given a positive word to remember, then another math problem — a sequence repeated six or seven times. At the end, participants were shown a matrix of words and asked to identify them in the order that they were presented.

Depressed participants tended to have more difficulty. Beevers attributes this to less activity in parts of the brain that are involved in effortful decision-making. Emotional processing is intact, so they are sensitive to these mistakes and far less able to process rewards and integrate that into their decision-making.

“It’s actually pretty hard for most people, but what we find is depressed people in particular are pretty bad at this, but they get better as they do more of this practice,” Beevers says. “Even more importantly, we find that this can reverse decision-making deficits and enhance reward processing difficulties that they had originally. And they actually report feeling less depressed, which is the exciting part of this.”

College Students Benefit from CARE

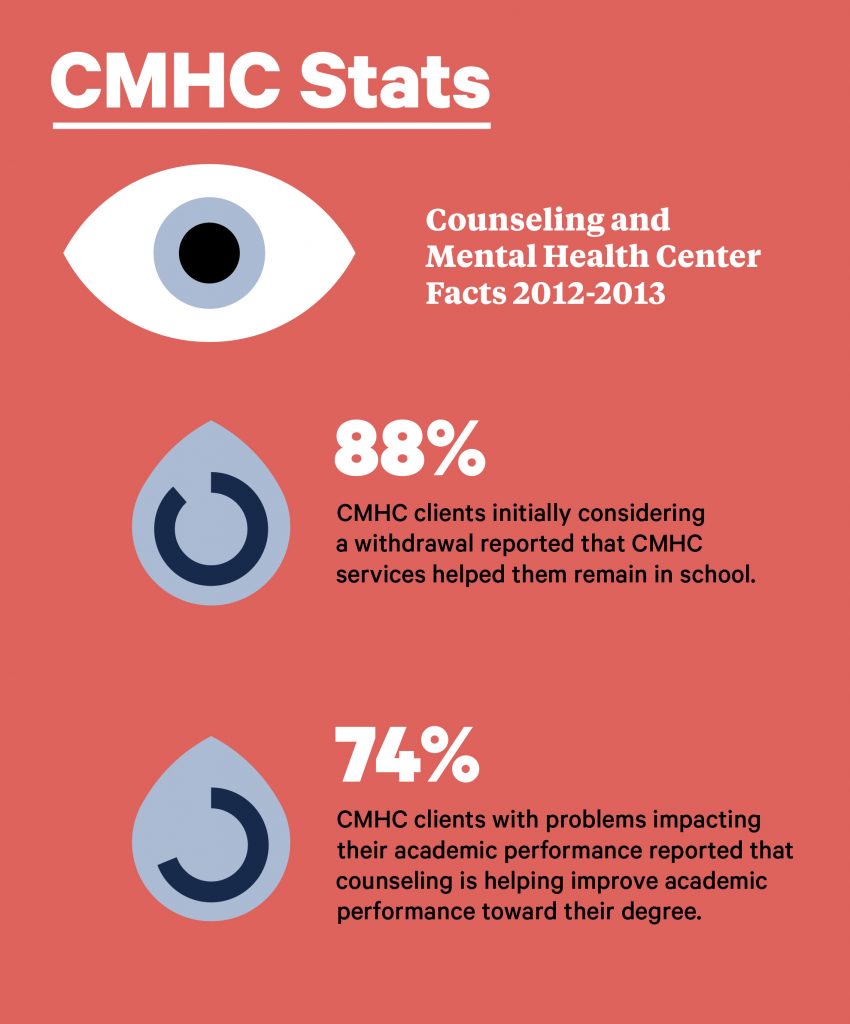

Many people may experience their first symptoms of depression during college, according to the National Institute of Mental Health. National trends suggest that more college students are seeking help at their college counseling centers for a variety of concerns including stress, depression and anxiety. UT Austin’s Counseling and Mental Health Center (CMHC) sees more than 23,000 students each year.

“This could be due to a decrease in stigma around mental health, a growing awareness of mental health resources or early identification,” says Alicia Enciso Litschi, a CARE counselor at the CMHC who serves Liberal Arts students.

The Counselor in Academic Residence (CARE) program is a new program at UT Austin that integrates counselors into academic spaces to make students feel more comfortable about seeking support.

According to an American College Health Association Survey, students identify “stress” as their biggest impediment to academic success — 51 percent of students said they felt overwhelming anxiety in the previous 12 months, and 11 percent indicated that they were diagnosed or treated for depression. Without adequate support, those students are more likely to receive low grades or drop out of college.

The CMHC offers a variety of resources for UT Austin students including short-term individual counseling, same-day walk-in crisis services and a MindBody Lab where students can explore resources for improving emotional and physical health without an appointment. It also offers group-counseling options for depression, anxiety, social connections, interpersonal communication and managing stress.

“It is normal to experience ups and downs throughout the semester — some bad days or even a rough week,” Litschi says. “However, it is important for students to recognize if they are beginning to feel worse more frequently and for a longer period of time.

“Oftentimes, students who are experiencing depression will begin to notice that they can no longer engage in school work and things they previously enjoyed,” she adds. “That’s when it’s important for students to seek help.”

Depression can be isolating, so Litschi says the act of reaching out is an important step to getting better. That could mean receiving counseling or enlisting the support of relatives, mentors or friends.

Gender and Job Authority

Job authority is typically related to higher earnings, power and job security — benefits that are often associated with better physical and mental health.

However, Tetyana Pudrovska, a sociologist and faculty affiliate in the Population Research Center, found that women with job authority — responsibilities to hire, fire and influence pay — experienced an increase in depression compared with men who have job authority and women who don’t have job authority.

“Higher-status women are often exposed to overt and subtle gender discrimination and harassment,” Pudrovska says. “This strain can undermine or reverse the health benefits of job authority.”

The study, “Gender, Job Authority, and Depression,” published in the Journal of Health and Social Behavior, considered more than 1,300 middle-aged men and 1,500 middle-aged women. It emphasizes broad societal factors and cultural and social forces, including unfavorable stereotypes, social isolation and resistance that make leadership excessively stressful for women.

She notes the proliferation of books and advice during the past several years encouraging women to be more confident and ambitious and to strive for leadership and visibility.

“Many of these recommendations focus on individual behavior as if it occurs in a vacuum outside of a broader social context and structural constraints,” Pudrovska says. “The message is that it is women themselves who are responsible for their lack of authority and confidence, so the recipe for rectifying the gender imbalance is for women to change their behavior. But changing individual behavior without addressing organizational and social contexts will not bring desired outcomes.

“Women’s leadership is good for women themselves, for other workers and for productivity,” Pudrovska says. “What is not good is the fact that there are numerous manifestations of gender inequality that impose extra stress on women in leadership positions.”

She recommends policies and workplace interventions aimed at reducing exposure to stress and increasing psychosocial rewards of job authority among women. She specifically recommends addressing unique challenges, improving well-being and increasing nonpecuniary rewards of leadership and retention rates of women with job authority.

“Targeting these stressors is an important step to enhance the psychosocial benefits of higher-status jobs for women and to increase retention in leadership positions of women in current and future generations,” Pudrovska says.

By taking a closer look at gender differences in the workplace, genetics and environmental stressors, UT Austin faculty members and staffers are working to apply research into viable treatments and support.

“There is a lot of human suffering associated with depression,” Beevers says. “So if we can identify some ways in which to help alleviate that and help people return to more normal, functioning lives more quickly, that can have hugely important consequences.”