Since Janet Davis’ early childhood in Honolulu, Hawaii, she says she remembers a life surrounded by animals: chickens running around the yard, horse rides, caring for her pet dogs and cats.

“It was a world saturated with animals, the formation of my moral consciousness, if you will,” says Davis, associate professor of American studies at The University of Texas at Austin.

Davis says her latest book, The Gospel of Kindness: Animal Welfare and the Making of Modern America (Oxford University Press, April 2016) — which marks the 150th anniversary of the nation’s first animal protection society, the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) — cumulated from her personal interest and unanswered questions from her previous research.

“I wondered about these animal protection societies,” Davis says. “What were they about? How did they come to be? What kind of social problems gave rise to organized animal advocacy?”

The Power of Photography

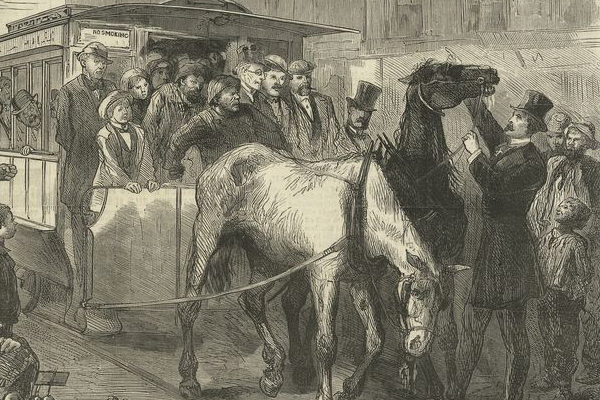

One catalyst for the animal advocacy movement came in the immediate years after the Civil War — a war fought with horsepower.

“The Civil War was a reckoning of giant proportions of rethinking, fighting and shedding blood over the questions of slavery, citizenship and rights,” Davis says. “Additionally, photography was documenting battlefield carnage more extensively than ever before.”

Mathew Brady and his corps of photographers took upward of a million images scattered around the battlefields — photographing dead soldiers and dead horses side by side.

On Sept. 19, 1862, a couple of days after the Battle of Antietam — the bloodiest day of battle in American history, with almost 23,000 people killed, injured or missing — Brady and his team photographed the dead. In October, his studio in New York City hosted the exhibition, The Dead of Antietam.

“You see these haunting photographs of horses that had died, people that had died, and you see what Drew Gilpin Faust, historian and president of Harvard University, calls ‘this republic of suffering,’ in immediate, painful detail,” Davis says. “Suffering was endemic in this deeply divided country at war.

“Questions about rights and citizenship were not being applied directly to animals, mind you,” she adds. “No one was thinking about animals as citizens, but they were thinking about animals as suffering fellow creatures.”

The Enforcer

During the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln appointed shipping heir Henry Bergh to serve as secretary of the legation in St. Petersburg, Russia. In 1862, Bergh and his wife, Matilda, traveled to St. Petersburg.

“While he was in Russia, he was appalled when drivers would beat their horses,” Davis says. “He tried to intervene and they laughed at him. They would say, ‘Who do you think you are?’

“One day he’s wearing his full legation dress — he has his ribbons and his medals —the formal dress of a diplomat,” she says. “He stands over 6 feet tall, so he’s a spectacular sight to see. He comes striding out in his colorful dress and silks, and he tells a driver to stop beating his horse and the driver immediately complies because he now sees Bergh as an authority figure, and Bergh realizes, ‘Perhaps I can use my lace to good measure.’”

When Bergh returned to New York, he enlisted the help of some powerful allies such as Ezra Cornell, a legislator and founder of Cornell University; and ironically John Jacob Astor, the fur magnate.

“We speak for those who cannot speak for themselves.”

ASPCA motto

The New York Legislature incorporated the first animal protection society on April 10, 1866. The next day, an ASPCA officer arrested a driver for stacking bawling calves in a wagon bound for market. Days later, Bergh and his allies spearheaded a new state anti-cruelty law, which was amended in 1867 to prohibit additional forms of cruelty, including blood sports and abandonment.

“Older legislation treated animals purely as property. New laws still considered animals to be property, but they also recognized an animal’s right to protection and to exist without undo suffering,” Davis says. “This marks a real departure.”

There was a previous animal protection law on the books in New York dating back to 1829, but the big difference was that the ASPCA was vested with the power of enforcement.

Animal Welfare & the Making of Modern America

Oxford University Press, April 2016

By Janet M. Davis, associate professor,

Department of American Studies

“Members of this society could actually arrest people for beating a horse or hurting a dog in public or any number of acts of physical abuse or neglect,” Davis says. “So this is a huge change.”

One historical curiosity Davis came across in her research was the interconnection of the formalized animal and child protection movements. In fact, the animal welfare movement actually came first.

In 1874, a woman seeking help for an abused child in a New York City tenement was frustrated by the reluctance of local law enforcement officers to intervene, so she reached out to Bergh and his chief legal council Elbridge Gerry, who secured an arrest warrant that resulted in a felonious assault conviction. In 1875, Gerry founded the first Society of the Prevention of Cruelty to Children in New York.

“These activists believed that the least among us, whether human beings or animals, deserve legal protection.” Davis says. “So in new dual humane societies, activists expand their reach to protect the most vulnerable including the aged, children, mothers, the poor and, of course, animals.”

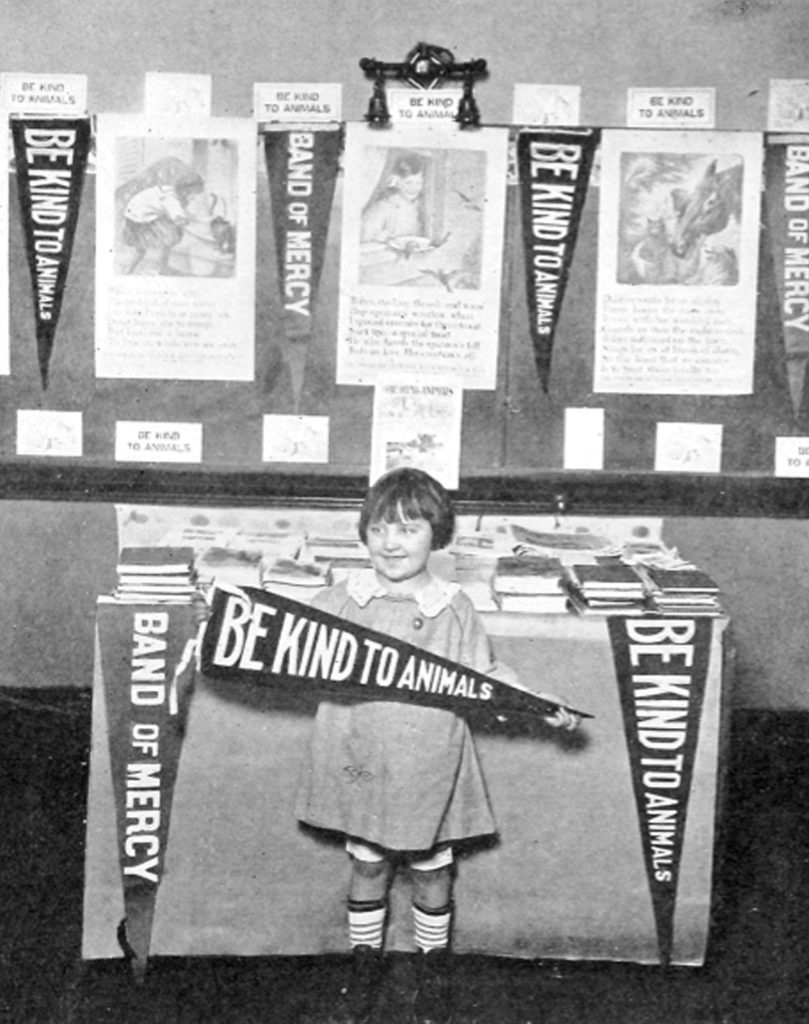

The Educator

Unlike Henry Bergh, who was born into great wealth, George Angell, the founder of the Massachusetts SPCA, was not. Angell’s father, a Baptist minister, died when Angell was a small child, and his mother was forced to return to teaching and had to put her son in the care of relatives.

“They wrote to each other all the time,” Davis says. “I’ve read their letters, and she was constantly worried about young George’s moral development. ‘Have you gone to the revivals? I’m worried about you. The snares of youth are very tempting, and I fear your soul will spiral into damnation.’ He’s eight years old.

“She’d write long motherly letters full of anxiety about the precarious state of his soul and then in the next line: ‘I have sent you the socks,’” Davis adds. “It’s this fascinating mix of moral reckoning and ordinary matters.”

As an adult, Angell read a shocking newspaper story about a horse race from Worcester to Brighton, Massachusetts, in which the horses were raced at top speed for 40 miles. They collapsed and died.

“It was a terrible event, an abusive spectacle,” Davis says. “Angell took decisive action immediately. In 1868, he creates the Massachusetts SPCA, and he propels the movement in new directions.”

Davis says Bergh would stop drivers in the street and say: “Stop. You may go no farther until you lighten that load.” Crowds would gather and sometimes fights would break out. Angell learned from these scenes of urban conflict.

“These public confrontations generated controversy. Critics charged that the ASPCA was picking on poor people whose livelihood was dependent on animal muscle,” Davis says. “As a result, Angell and Bergh, too, eventually realized that education instead of prosecution was a more productive path.”

Angell immediately printed 200,000 gratis copies of the publication Our Dumb Animals. The title reflected an earlier usage of the word “dumb,” as in not being able to speak. The motto for the organization was “We speak for those who cannot speak for themselves.”

Angell had 30,000 copies handed out within Boston, enlisting the help of police officers with distribution. The remainder were mailed to missionary organizations, temperance societies and reformers whose work he respected in other countries and with whom he hoped to create alliances.

“What that did right from the start was to establish a good working relationship with local police,” Davis says. “Then he sent copies to people around the world. People he deemed to be important.

“He was thinking globally about his movement from the beginning,” she adds. “He believed in an ethic of kindness to reimagine who we are as a people.”

In 1889, Angell created the American Humane Education Society, an organization dedicated to the belief that education programs instead of prosecution would foster permanent generational change.

Give Me Shelter

Caroline Earle White, the co-founder of the Pennsylvania SPCA and its women’s branch, brought together different strands of the animal advocacy movement by providing more humane forms of capture, shelter and adoption.

“She had cared about animal protection since childhood, but as a woman she worried about the proper course of action,” Davis says. “For Bergh, stopping horses physically with his body was a perfectly appropriate standard of conduct for a man in public in the 1860s, but it certainly was not proper behavior for a respectable lady.”

Every summer, cities across America would conduct massive dog roundups because people thought rabies proliferated in hot weather. Dogs were thrown into wagons, sometimes shot on site or placed in big riverside iron maidens and drowned.

“Gilded Age newspapers frequently chronicled the brutality of the local pound, dog catchers and cases of people — usually poor, immigrant born or people of color — trying to shield their dogs,” Davis says. “In one case, for example, a dog catcher fatally shot a little boy outside in Harlem who refused to give up his pet.”

In response to these social injustices, White and her female colleagues leased the Philadelphia pound and hired their own people. They instituted a year-round schedule for catching strays instead of just focusing on the summer months, and they implemented humane methods of capture.

The pound was renamed a shelter. Food and water were provided for the animals, as well as play areas. Fines were made more affordable. Over time, they emphasized adoption rather than euthanasia.

“It was spearheaded by women working inside the domestic space of the shelter, so again these ideas about proper womanhood were validated, rather than challenged,” Davis says. “They also did not seek the power of prosecution in their state charters. They sought power to create these shelters.

“So this is another strand of the movement that expands nationally. It’s led by women and it endures,” she adds. “It becomes a defining feature of modern animal advocacy.”

Happy Tails

On July 23, 2006, a week before Davis kicked off her research travel for the Gospel of Kindness, she got to experience the animal advocacy movement a little closer to home.

She was riding her bike home when two stray dogs approached her.

“They looked at me and started wagging and followed me all the way home. My husband said: ‘no, no, no, and my kids said yes, yes, yes,’” Davis laughs.

After trying to locate the dogs’ owners to no avail, Davis and her family decided to adopt the two dogs, but she still had to travel to the Massachusetts SPCA archives in Boston. Back at home her husband cared for the two dogs not yet housebroken.

“For a solid week, I pored through the archive. When I left each evening, I’d talk on the phone to my husband while riding a trolley to Cambridge where I was staying. My husband would unleash a volley of

complaints about the unruly dogs,” Davis quips. “Meanwhile, at the MSPCA, the person I worked with who was also in charge of adoptions was saying ‘Bless you. Great job!’

“My dogs are still thriving, and they’ve been with me as I’ve researched and written this book. They’re my buddies: Duke and Lincoln,” Davis adds. “The fact that I would turn first to our local animal shelter upon finding these stray dogs is a testament to the enduring impact of a social movement that began 150 years ago to protect our fellow creatures.”