For more than a century comic strips have provided a light-hearted diversion for newspaper readers, although a few were groundbreaking for the insights they offered about society. Peanuts captured Cold War anxieties with the existential musings of chronically depressed Charlie Brown, while the anthropomorphic Pogo and his friends in Okefenokee Swamp provided the era with biting political satire.

Another groundbreaking cartoonist who explored Cold War-era society and politics was Jackie Ormes, long celebrated as the first African American female cartoonist. A sampling of her work was recently on display in the Gordon White Building in an exhibition curated by Rebecca Giordano on behalf of the graduate student collective INGZ and the Warfield Center.

In her comments on the exhibit, In Heartbeats: the Comic Art of Jackie Ormes, Giordano notes that Ormes used her irreverent and witty comics to tackle major cultural events that centralized the experience of African American women.

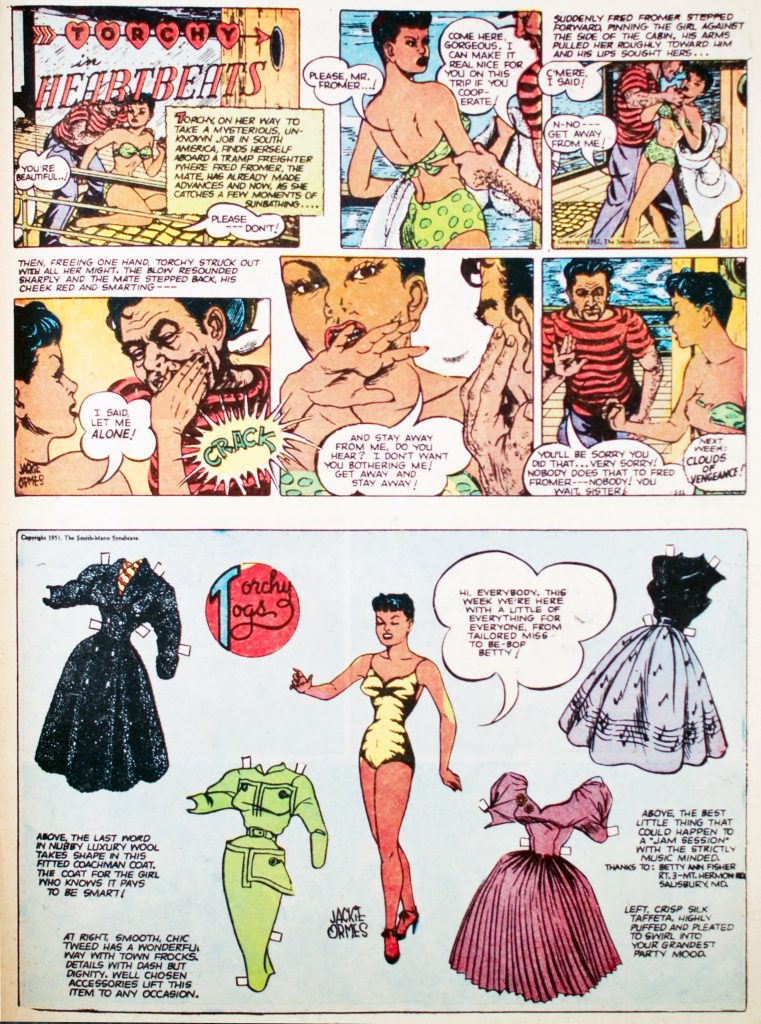

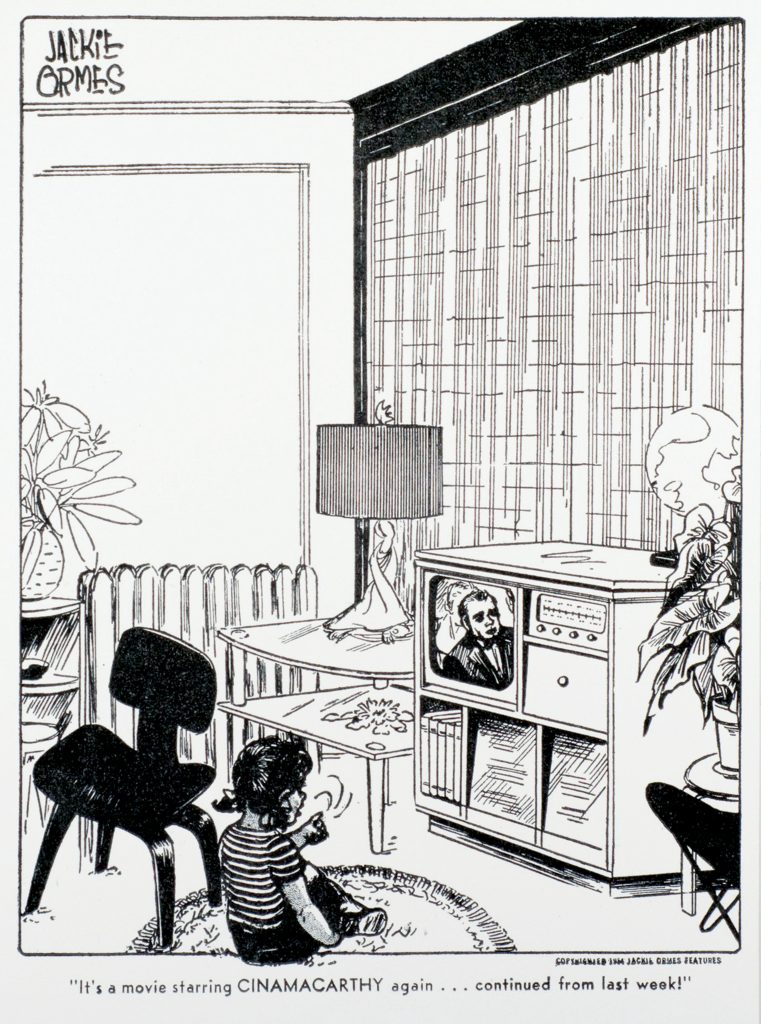

“From the House of Un-American Activities to segregated train cars that enabled the Great Migration, Ormes’ vivacious and intellectual characters countered pervasive stereotypes with images of stylish, self-driven, and savvy women of color,” notes Giordano.

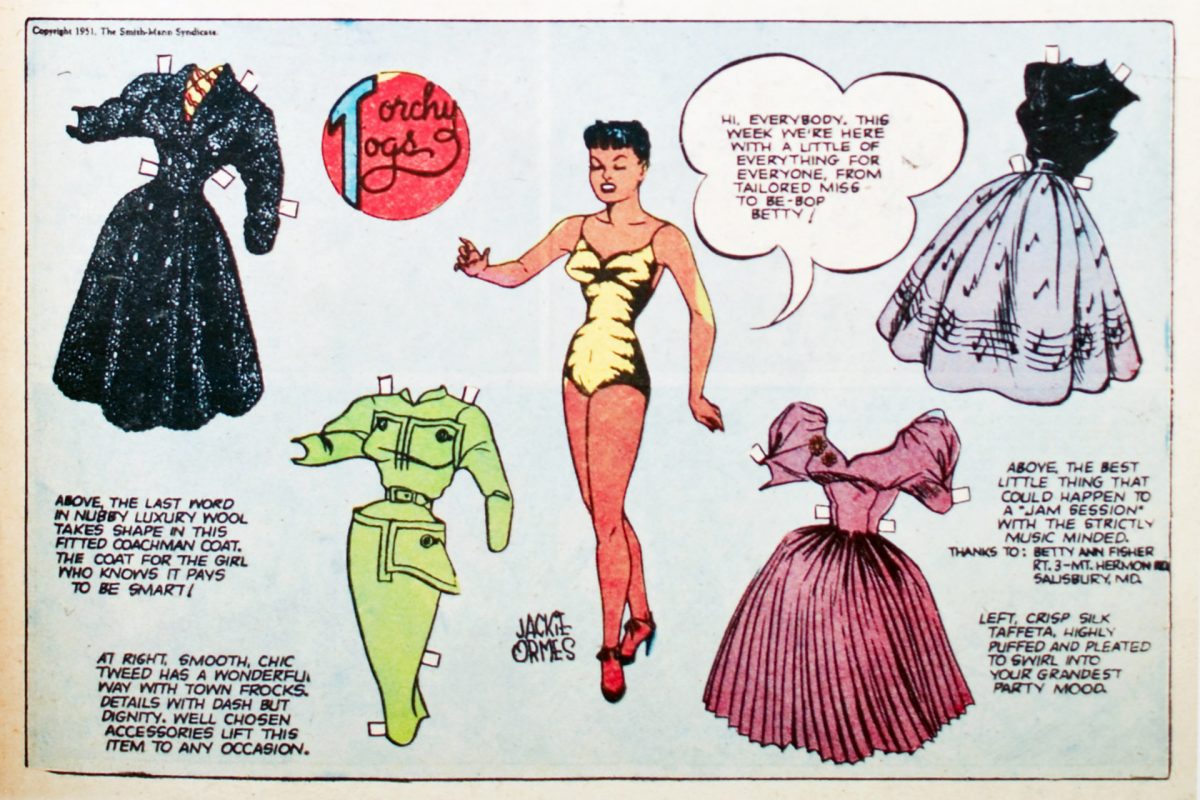

Ormes (1911-1985) began publishing the strip Dixie to Harlem for The Pittsburgh Courier in 1937, featuring Torchy Brown as a character who moves from the fields of Mississippi to the stage of Harlem’s famed Cotton Club. Ormes went on to publish three other comic series: Candy (1945), a peek into the private frustrations of a witty maid employed by an absent white woman; a revival of the Torchy character in Heartbeats (1950-54); and her most popular comic, Patty-Jo ‘n’ Ginger (1945-56).

Giordano notes that perhaps because of her art and her participation in black leftist intellectual circles of Cold War-era Chicago, Ormes was under surveillance by the FBI, which amassed a file of more than 250 pages from 1948 to 1958. In addition to racial injustice she also addressed issues related to foreign policy, environmental pollution and war.

Ormes also brought attention to the way African American women used fashion and dress as tools for self-determination and positive self-representation. Giordano notes that through her comic art, paper doll designs published with Torchy in Heartbeats, and a plastic doll based on Patty Jo, Ormes allowed readers the opportunity to generate narratives of their own and combat racist and sexist caricatures that were prevalent in mainstream media.