After months of being bombarded by pollsters, campaign ads and the most outlandish sound bites on repeat, the moment will come for you to finally cast your ballot.

Whom will you choose?

“The presidency is the one office that represents the American people: all their wishes, dreams, desires, hopes, fears and everything else,” says history professor H.W. Brands. “The president is supposed to stand for everything that America wants in the world, everything that Americans hope to have.”

But in a country of 324 million people, Americans’ wants and dreams are subjective. “We often speak of the ‘American People.’ There is no ‘American People.’ There are lots of different people with lots of different ideas,” Brands says.

So, oftentimes voters are told what they should want and need through careful campaign messaging that is structured to fabricate needs, heighten anxieties and trigger unsolicited desires for certain policies — all to convince voters that only one candidate can be trusted with the job.

Product Development

“Presidents are like soap, toothpaste or any other product,” says government professor Daron Shaw, referencing The Selling of the President, written by Joe McGinniss about the 1968 campaign. “You’re constructing an image, you’re selling an image and you’re contrasting that image with the competition.”

In the metaphor, presidential candidates are the products of political parties, sold to voters with a promise of addressing and fixing the most pressing problems that face the country and the world today — be it foreign, domestic or economic.

But behind every candidate’s proposed solution hides a partisan agenda rhetorically disguised to sway nonpartisan voters to choose a candidate rather than a party.

“Parties are brands, and the brands are really damaged,” Shaw says.

According to the Pew Research Center, nearly 40 percent of voters are unaffiliated with a major political party. Some see the growing distrust for parties as a result of polarization, which has roots in a realignment that took place in the 1960s. Prior to that, both parties were what Brands describes as philosophical coalitions consisting of liberal and conservative Democrats and liberal and conservative Republicans.

The change came when President Lyndon Johnson embraced the cause of the civil rights movement, alienating many southern conservative Democrats, who believed that the federal government overstepped its boundaries on an issue that should be handled by the state.

“In terms of polarization in politics, it is more extreme now than it was for most of American history,” Brands says. “Nowadays it’s impossible to get the kind of bipartisanship that was possible in the 1960s, even as late as the 1980s.”

Since then, Republicans have become the more conservative party on economic, social and racial issues, and the Democrats more liberal.

It’s a double-edged sword, Shaw explains. On one hand, there is gridlock. But on the other, the parties offer clear alternatives for different issues and are more ideologically consistent and coherent than they were in the 1960s.

The Competition

Although the parties have become more ideologically aligned, the public has not.

“Public opinion tends to be fairly centrist, with pockets of extremists on both sides of the issue,” Shaw says. “They side one way or the other, but they aren’t intense in their opinions, and that hasn’t changed much since the 1970s.”

But although the public remains more “reasonable,” the elites and candidates running for office take more consistent and extreme positions, Brands says.

“There’s something about politics that brings out the unreasonableness in people,” Brands says. With the loss of competitive districts, which promote more competition within each party during primaries, partisan cohorts are pushed to their “zealous” extremes.

“Redistricting has had a terrible effect of insulating and isolating our elected officials,” says Victoria DeFrancesco Soto, a lecturer of Mexican American and Latina/o studies. “You end up with politicians that are so Republican or so Democrat because of their districts with no incentive to work together.”

“Presidents are like soap, toothpaste or any other product. You’re constructing an image, you’re selling an image and you’re contrasting that image with the competition.”

Daron Shaw

As a result, the “centrist,” “reasonable” public is forced during the general election to choose between two ideologically distinct candidates, making it less likely for partisans to favor a candidate of a different party and forcing unaffiliated voters to choose a side.

“Polarization at the mass level is largely about attitudes toward the political parties that put these candidates up,” Shaw says. “What you see is Republicans think worse of Democrats, and Democrats think worse of Republicans than they did in the 1970s. And there’s less defection in the elections.”

In turn, candidates have to work against the negative stigma surrounding their party by promising the moon to their voters and shifting the negative focus to the other side of the aisle.

“I’ve long thought that Americans would start being less disillusioned by their presidents when they start to insist on being spoken to as adults by candidates,” Brands says, but voters don’t want to hear from realistic candidates.

“Candidates who take a more realistic view get either shouted at or voted down in the primaries, because primaries in some ways are just a way for people to register their emotions rather than to make any kind of substantive decision,” he says.

Shaw agrees: Campaigns have always been and continue to be negative and trivial.

“The means by which these brands are established and sold has become kind of nasty, and the process has become somewhat uglier than it used to be,” Shaw says. “But you have to keep people interested and involved. That’s the price you pay for popular democracy.”

Target Audience

Much like a marketing campaign, a successful political campaign consists of a plan to win, Shaw says. It identifies whom a candidate will speak to and what he or she will say.

“Candidates need to identify which people will help them achieve their minimum winning coalition,” he says. “In the general election, identifying constituencies is critical to deciding whether Republicans or Democrats win.”

Setting strong partisans aside, both parties will turn their efforts to the more moderate and unaffiliated voters, with a special focus on Latinos and middle-class whites, Shaw explains.

“After 2012, the conversation was that the Democrats were the party of the future because all of their voters were a growing portion of the electorate, while Republicans were becoming less prominent,” Shaw says.

The U.S. census indicates that the Latino population has grown to become the nation’s largest ethnic minority, with an increase of 1.15 million Latinos added to the nation’s population between July 2013 and July 2014 alone. The non-Latino white population has shrunk, and the black population has remained steady.

“But, demographics are not destiny,” DeFrancesco Soto says, noting that the Latino population is disproportionately young. The average age of a non-Latino, white person is 48; the average age of a Latino is 27; and the average age of a U.S.-born Latino is 18.

“The good news is the electorate has been growing,” she says. “The bad news is we’re probably not going to see a lot of impact in this election because young people don’t vote — black, white or brown: young people don’t vote.”

In another report from the Pew Research Center, a record number of Latinos —27.3 million — are eligible to vote in the 2016 election; however, 44 percent of those voters are millennials.

Although many people assumed young voters to be Democratic after the Obama elections, Shaw says they are more distinguished by their disaffection with politics, and he thinks there are other constituents that campaigns should focus on.

For Democrats, it is middle- and lower-middle-class white voters who are socially conservative but support liberal government-spending programs. For Republicans, it is suburban voters such as those in the collar counties surrounding Philadelphia and Detroit.

“There’s a growing obsession with ‘waitress moms’ and ‘NASCAR dads,’ and ‘soccer moms’ and ‘office park dads,’ ” Shaw says, laughing it off as a “marketing fight” between campaign consultants. Nonetheless, he says micro-targeting voters in such ways will result in more support from the middle class as a whole.

And Latinos are no different, DeFrancesco Soto explains. Too often these voters are cast as a monolithic group when in fact nearly half of Latinos are unaffiliated with either party.

“We cannot lose sight of the diversity of Latinos — not just ethnically, but in terms of their ideology,” DeFrancesco Soto says. “At the same time, there are unifying, cultural ties within the Latino community. So, we have to embrace the diversity while recognizing commonalities by harnessing the power of micro targeting.”

Managing Media

To home in on subgroups of unswayed voters, candidates turn to media to get their names and messages out through broadcast, print, online and social media.

“Media has always been important in politics, especially in influencing the middle,” DeFrancesco Soto says. “Media is very powerful with the fence sitters.”

This is where campaigns get expensive, Shaw says. Though there is a rise in cheaper online campaigning tactics, television advertising continues to dominate the budget.

“There’s a bit of a food fight between online and television advertising,” Shaw says. “Television folks will tell you that no matter what online presence you have, television is the main means by which you carry messages to voters; and the online folks will tell you that they can target messages more effectively and at a much cheaper cost.”

Brands says this election is seeing the rise of “the media-driven candidate,” those who are taking advantage of free publicity and the cheapest promotional tactics, such as using social media.

This brings about the idea that someone could “tweet his way to the White House,” Shaw says. Though social media is powerful and pervasive, Shaw says he would advise candidates to reinforce their brands through wholesale politics, such as TV ads, and retail politics — going person to person to get the vote out. However, Shaw warns that the rogue operations and biased content may throw a wrench in the micro-targeting machine, creating more clutter for candidates to cut through to get to their constituents.

“This proliferation of media goes both ways. It’s good because you have all these outlets, but it’s bad because there’s so much clutter,” DeFrancesco Soto says.

With all the competing outlets, media opt for telling stories that sell the most papers rather than the stories that create the most informed public. The media’s stake is not to elect the best president; it’s to sell ads, Brands says.

“The partisan media is more striking than it was 50 years ago, but it’s like it was 200 years ago,” he says, pointing out that 19th century newspapers were attached to political parties. “It is different than it was in the 1960s when there were fewer papers and only three TV news networks operating under the Fairness Doctrine.”

But much like the 19th century, people subscribe to publications and seek stories that underline their ideas surrounding certain issues. And according to assistant professor of government Bethany Albertson, people gravitate toward news that reinforces emotions such as anxiety.

“We have a highly emotive media environment,” she says. “I don’t want to blame the media too much, but there are so many outlets and stories to choose from, that we need to recognize the way that anxiety biases the way we engage with that environment.”

Crafting the Message

“Emotions matter in politics — enthusiastic supporters return politicians to office, angry citizens march in the streets, a fearful public demands protection from the government,” reads the opening line of Albertson’s book Anxious Politics: Democratic Citizenship in a Threatening World, which she co-wrote with Shana Kushner Gadarian of Syracuse University.

In the book, Albertson and Gadarian examine how political anxieties affect public life in regard to the way people consume political news, whom they trust and what policies they support.

“The dominant idea was that anxiety is good for democracy because it causes people to learn,” Albertson says. “We were trying to reconcile that with what we knew about how politicians strategically use anxiety, which didn’t make us think that anxiety is always good for democracy.”

Albertson argues that people resolve anxiety related to politics by seeking out threatening information and trusting policies and politicians that promote a sense of protection. She says that partisanship “colors” what voters might view as protective.

“Anxiety doesn’t cause people to trust indiscriminately. Rather, it’s targeted to those organizations or individuals who are useful, given the subject of their anxieties,” Albertson says.

In other words, each party “owns” different issues. Political parties differ in terms of how much they are trusted with certain political issues. Their book uses the example of immigration as an issue area where anxiety benefits the Republican Party.

“Democrats will always trust Democrats more, and Republicans will always trust Republicans more,” Albertson says. “But if you get a Democrat anxious about immigration, it will push them more toward trusting Republicans, which is a sign that they own the issue.”

“Emotions matter in politics — enthusiastic supporters return politicians to office, angry citizens march in the streets, a fearful public demands protection from the government.”

Bethany Albertson

She says Democrats are more trusted on issues such as health care and climate change.

“Candidates want to promote anxieties that they are well positioned to calm people about,” Albertson says. “Candidates should pick issues that advantage their party.”

The book describes two types of threats. Unframed threats, such as a terrorist attack, pose imminent concern about bodily harm and result in widespread vulnerability and trust for whomever is in charge. Framed threats, such as immigration, vary based on what political elites tell voters and whether that message resonates.

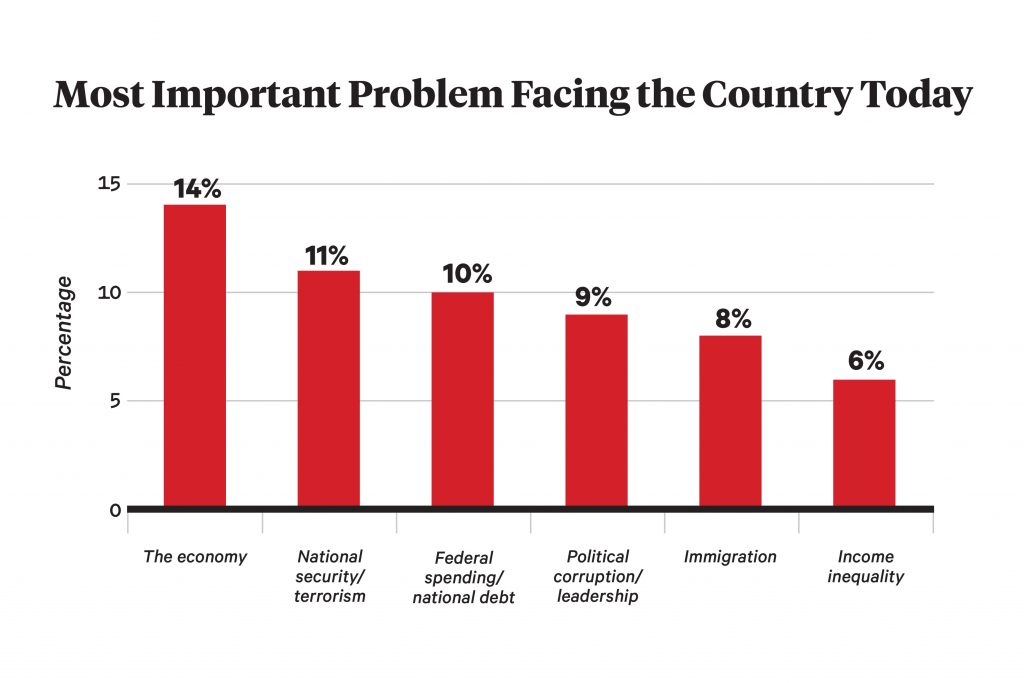

The topics stirring up the most anxiety this election cycle are immigration, foreign policy and economics, Albertson says.

Republicans appealing to more conservative voters might address frustrations surrounding rapid demographic changes. Republicans courting the Latino vote may use moderate views on immigration to appeal to anxieties surrounding a pathway to citizenship, says DeFrancesco Soto, emphasizing that the tone on immigration is a gateway to gaining support among Latino groups.

“For Latinos, the top issue is the economy,” she says. “But the tone of immigration is kind of a slippery concept for Latinos. If they don’t like a candidate’s tone, they aren’t going to support the rest of what he or she has to say.”

Democrats might frame messages on economic inequality to address anxieties of economic hardship, pointing out how the system is rigged or stacked against a certain group and offering policies to protect voters from it, Albertson says.

“There’s a lot of anxiety on both sides of the election so far. It seems like we don’t have a politician out there with a positive message,” she says.

And she might be right.

The Pitch

“It’s easy to control what we talk about, but not how we talk about it,” says psychology professor James Pennebaker.

He and psychology graduate student Kayla Jordan analyzed candidates’ language throughout the 2015 and 2016 debates using a program called Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC), which measures about 80 psychological dimensions.

According to their analysis, candidates’ use of risk-oriented words is greater in the context of foreign policy and immigration, using words such as avoid, defense, danger and disadvantage.

Using words in this way raises the issue of fear mongering in politics. Because it is hard to judge when candidates are being cynical and when the threat is real, fear mongering can be an appealing and effective tactic, says government professor Bruce Buchanan.

“You wouldn’t hear that sort of an alarmism coming out of a president,” he says. “You may hear alarmism from a candidate because a candidate is not responsible for anything unless he or she is elected. But fear mongering can stimulate support.”

When it comes to appealing to the public as a whole, however, Buchanan suggests that rather than selling fear, candidates should walk the walk and talk the talk of a U.S. president.

Democratic Citizenship in a Threatening World

Cambridge University Press,

Sept. 2015

By Bethany Albertson, assistant professor, Department of Government; and Shana Kushner Gadarian

“You’re auditioning for the presidency, which is an office that is responsible to all the people,” he says. “You have positions that you are advocating for, but you also want to speak as if you are aware that you are seeking to become president of all the people.”

By plugging in past presidential inaugural speeches into LIWC, Pennebaker and Jordan determined how presidential language should sound.

“Presidents tend to use more articles, prepositions, positive emotion and big words,” Pennebaker and Jordan wrote in their blog “Wordwatchers” (wordwatchers.wordpress.com).

These candidates may be judged by voters to be better suited for the office than candidates who sound less presidential, they add.

Buchanan, who conducts in-depth research on presidential approval ratings, agrees that no matter what policies a candidate may be pushing, the key is likeability.

“The currency of the presidency is popularity,” he says. “The American people judge them in the here and now based on what they’re doing, whether they like their smile, traits and acts, as well as some sort of short-term kind of result.”

Plenty of literature supports the idea that people support charismatic leaders, those who are friendly and powerful, Pennebaker says. But another argument suggests that it depends on the context. Pennebaker adds that if voters feel threatened, they may flock toward someone who is more task-oriented and focused rather than a “buddy.”

“Every state has a different agenda and a different personality or profile, so to speak,” Buchanan says. “It’s tricky because you can’t appear as blatant as a chameleon, changing your identity just to please some current audience.”

Come Nov. 8, a person’s vote will go to the candidate who looks and sounds most like a president, despite the fact that he or she has never been one, Buchanan says.

“America will choose a person well prepared in policy, who projects self-confidence, gravitas and dignity, which most people think are required for the presidency,” he says. “The candidate whose proposals seem to be logical solutions to the problems that Americans are worried about: domestic, economic and foreign.”