Sharp, clean breaks on the right arm of the oldest, most famous fossil of a human ancestor reopened the coldest cold case in human evolution.

Lucy, a 3.18-million-year-old specimen of Australopithecus afarensis — or “southern ape of Afar” — is among the oldest, most complete skeletons of any adult, erect-walking human ancestor. Since her discovery in the Afar region of Ethiopia in 1974, two questions remain: Did her species spend any time in trees, and how did she die?

During her U.S. exhibit tour in 2008, Lucy detoured to the High-Resolution X-ray Computed Tomography Facility in the Jackson School of Geosciences — a machine designed to scan through rock-solid materials at a higher resolution than medical CT scans can. For 10 days, anthropology professor John Kappelman and geological sciences professor Richard Ketcham carefully scanned and created a digital archive of Lucy’s 40-percent-complete skeleton.

Studying the CT scans years later, Kappelman noticed something unusual: The end of the right humerus was fractured in a manner not normally seen in fossils, preserving a series of sharp, clean breaks with tiny bone fragments and slivers still in place.

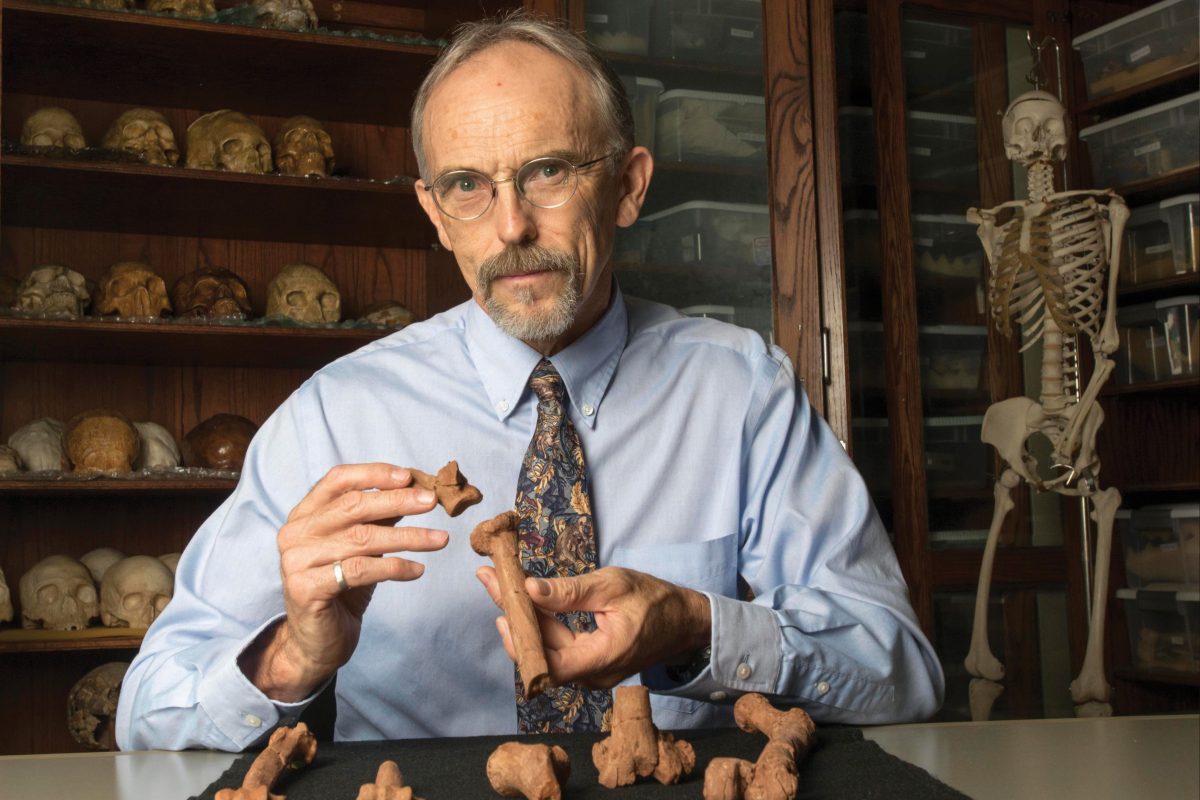

Kappelman, whose findings are published in Nature, identified the damage as a textbook case of a four-part proximal humerus fracture — a “compressive fracture [that] results when the hand hits the ground during a fall, impacting the elements of the shoulder against one another to create a unique signature on the humerus,” says Kappelman, who consulted and confirmed his hypothesis with Dr. Stephen Pearce, an orthopedic surgeon at Austin Bone and Joint Clinic, using a modern human-scale, 3-D printed model of Lucy.

Her skeleton contained similar but less severe fractures at the left shoulder and other compressive fractures, including a pilon fracture of the right ankle, a fractured left knee and pelvis, and even more subtle evidence, such as a fractured first rib — “a hallmark of severe trauma” — all consistent with fractures caused by a fall. Without any evidence of healing, Kappelman concluded the breaks occurred perimortem, or near the time of death.

The question remained: How could Lucy have achieved the height necessary to produce such a high velocity fall and forceful impact? Kappelman argued that because of her small size — about 3 feet 6 inches and 60 pounds — Lucy probably foraged and sought nightly refuge in trees.

In comparing her behavior with average chimpanzee nesting and foraging heights, Kappelman suggested Lucy probably fell from a height of more than 40 feet, hitting the ground at more than 35 miles per hour. Based on the pattern of breaks, he hypothesized that she landed feet-first before falling forward, bracing herself with her arms, and “death followed swiftly.”

“When the extent of Lucy’s multiple injuries first came into focus, her image popped into my mind’s eye, and I felt a jump of empathy across time and space.”

John Kappelman

“When the extent of Lucy’s multiple injuries first came into focus, her image popped into my mind’s eye, and I felt a jump of empathy across time and space,” Kappelman says. “Lucy was no longer simply a box of bones, but in death became a real individual: a small, broken body lying helpless at the bottom of a tree.”

Kappelman conjectured that because Lucy was both terrestrial and arboreal, features that permitted her to move efficiently on the ground may have compromised her ability to climb trees, predisposing her species to more frequent falls. Using fracture patterns when present, future research may tell a more complete story of how ancient species lived and died.

UT Austin Professor John Kappelman with 3-D printouts of Lucy’s skeleton illustrating the compressive fractures in her right humerus that she suffered at the time of her death 3.18 million years ago.