The bravest are surely those who have the clearest vision of what is before them, glory and danger alike, and yet notwithstanding, go out to meet it.

– Thucydides

Oftentimes, we are met with spectacular images of war, depicting valiance and vilifying enemies; but these stories, some say, lack an honest narrative.

While soldiers undoubtedly exhibit heroic traits, these moments don’t define every veteran. Rather, it’s the day-to-day interactions, months of training and years of service that define their experiences; and it’s their reflections on what they endured that qualify who they are.

“We either talk about those who serve as heroes or as people who need to be helped,” says Army veteran Bart Pitchford. “That kind of binary view is not only dangerous for the relationships of America with its military, but it is dangerous for the individual veteran.”

Pitchford served active duty in the United States Army for six years and in the Army Reserves for two, completing tours in Baghdad, Iraq in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom (2007-2008) and Sana’a, Yemen (2009) and Islamabad, Pakistan in support of Operation Enduring Freedom (2011).

“The world of the soldier and the world of the civilian are on completely different planets,” Pitchford says. “I believe one way to bring those worlds closer together is for communities to see the real life of a soldier. We need to cut through the stories of trauma and heroism that only reinforce the wall between soldier and citizenry.”

As a Ph.D. candidate in performance as public practice at The University of Texas at Austin, Pitchford leads a group of veterans in the community in reflecting on their service through “The Warrior Chorus – Humanities in Action,” housed in the Department of Classics — a single component of a national program supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Aquila Theatre Company in New York City that brings together veteran communities at UT Austin, New York University (NYU), Columbia University and the University of Southern California in a ten-week, scholar-led workshop to study classical literature as it relates to contemporary America. The twice-weekly discussions springboard into public programming that motivates new dialogues about war, conflict, comradeship, country, family and politics.

“The community needs to see itself connected to these stories,” says Pitchford, who was named a 2015-2016 Teaching Excellence Fellow. “They need to interact with the veterans and their memories instead of being a passive depository for information. They need to become open to questioning the narratives, old and new, about what it means to serve in the military.”

Whoever neglects the arts when he is young has lost the past and is dead to the future.

— Sophocles

Because such a small percentage of the U.S. population experience military life, a natural disconnect has formed between the general citizenry and those who have chosen to serve, Pitchford explains, and fellow Army vet Meghan Richards agrees.

“Just by the numbers, you have such a small population involved in the U.S. military to tell their stories and experiences of being a part of it,” says Richards, a UT Austin senior majoring in health and society who joined the Warrior Chorus to enhance her knowledge and skills in the arts. “I’m hoping to develop a better grasp of storytelling and how it impacts audiences and to contribute to the accurate and genuine portrayal of veterans in arts and media.”

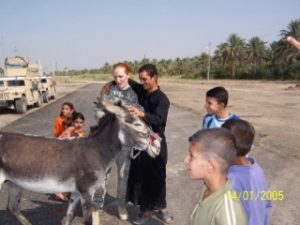

Richards, a former Army medic who completed two tours in Iraq in 2006 and 2008, says her experiences led her to studying health and society in order to expand her knowledge of preventing and treating injuries to the bigger picture of health and health care.

“The social, political and economic trends, disparities and real-world problems that face health care in America and the world-at-large today are varied and complicated, but also solvable,” says Richards. “The biggest impression that the military left on me was the idea that ‘where there’s a will, there’s a way;’ that there’s strength in numbers.”

Richard’s military identity and the notion of being a part of something bigger than oneself was instilled in her at a young age, along with her appreciation for the arts and musical expression. She grew up in a family of Air Force pilots, including her father, grandfather, uncle and brothers, and was immersed in music from church choir to living-room duets accompanied by her grandmother on the piano.

She is a singer songwriter with a “folksie” vibe, inspired by the musical stylings of Regina Spektor and Jewel and narratives drawn from her own life and the human experience. On Veterans Day, her song “We Might Not Agree” will make its debut on iTunes as part of the Operation Encore, which compiles original songs by soldiers and veterans about their experiences. She uses her music as an avenue for release when life’s stresses build up.

“I laugh about it. Sometimes I cry about it. Sometimes I completely ignore it. Sometimes I try to write or sing about it,” Richards says. “When I speak about being a veteran, I’m not speaking for all veterans. This is just my experience and there are many, many more.”

She hopes that by sharing her stories, she can promote a new image of the female warrior, a character often untold in stories of war, but a powerful and unique identity that the public should recognize and respect, just as they would a male soldier. “You can be a warrior and nurturer at the same time,” she says.

The most difficult thing in life is to know yourself.

— Thales

Sonia Parrish, a U.S. Marine veteran (1990-1994) from New Braunfels, Texas, says she grapples with her identity as a female Marine along with the emotional remnants of war as she unpacks her own stories. “I want people to understand what it’s like for a woman going into a group of men, and then coming out of it where societal norms of feminine are pushed on you,” she says.

“I’m a Marine before I’m a lady,” Parrish adds, pointing out that it’s much easier to identify as a veteran than who she is or was before the military.

“I really have a hard time overcoming things that happened to me during my military years,” Parrish says. “I was recently diagnosed with PTSD from physical and sexual assaults that occurred during my service, and I’m still trying to find my way back from all of that. But I think it will take a long time for me to find any resemblance of my former self.”

Her reflections have left her with feelings of loss from friends who passed in Desert Storm and loss of self due to the assaults she suffered; and from that, feelings of embarrassment; but above all, she feels proud as a Marine and deep support for veterans and staunch patriotism.

Parrish and Raul Gayton, her uncle who served in the U.S. Navy (1969-1971), drive from New Braunfels twice each week to attend the Warrior Chorus. The pair are virtually inseparable, with Parrish lovingly referring to Gayton as her “service human” who helps her cope with the safety concerns she faces daily as repercussions of the trauma she experienced.

“Because of my issues with PTSD, I have become somewhat of a hermit,” Parrish says. “I use my uncle as my crutch to keep me company and help me feel safe outside of my house.”

She was intrigued in the Warrior Chorus as an opportunity to study classical arts at a university she had long been interested in attending and to interact with other veterans who can offer both support and understanding. The weekly discussions, she says, are essential for healing and offer a similar camaraderie to that which she experienced in the military.

“It takes a certain type of person to be in the military and succeed,” Parrish says. “We feel the need to be protectors. That is our gift. When people run from danger, we are the ones running to it; but being protectors has a cost.”

She hopes that the public performances the chorus develops break the mold of how the public perceives soldiers, and sheds light on the human that exists underneath the “cammies.”

“I hope people understand that veterans are humans, just broken — some a little, others a lot,” Parrish says. “We aren’t crazy or brainwashed. We are broken because of the choice we made to keep others from harm’s way. But we are also mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, uncles, aunts, wives and husbands, just as they are.”

Knowledge, if it does not determine action, is dead to us.

— Plotinus

As a father, husband, engineer, student and former mayor Terry Orr, a former lieutenant in the Army (1961-1963) and captain in the Army Reserves (1963-1968), offers a narrative that is relatable across a spectrum of identities. His role as Mayor of Bastrop (2008-2014) and interest in ancient history, derived from his current studies as an undergraduate — yes, at 79 years old — in classical archeology, have made him a ‘guiding spirit’ to younger veterans in the Warrior Chorus.

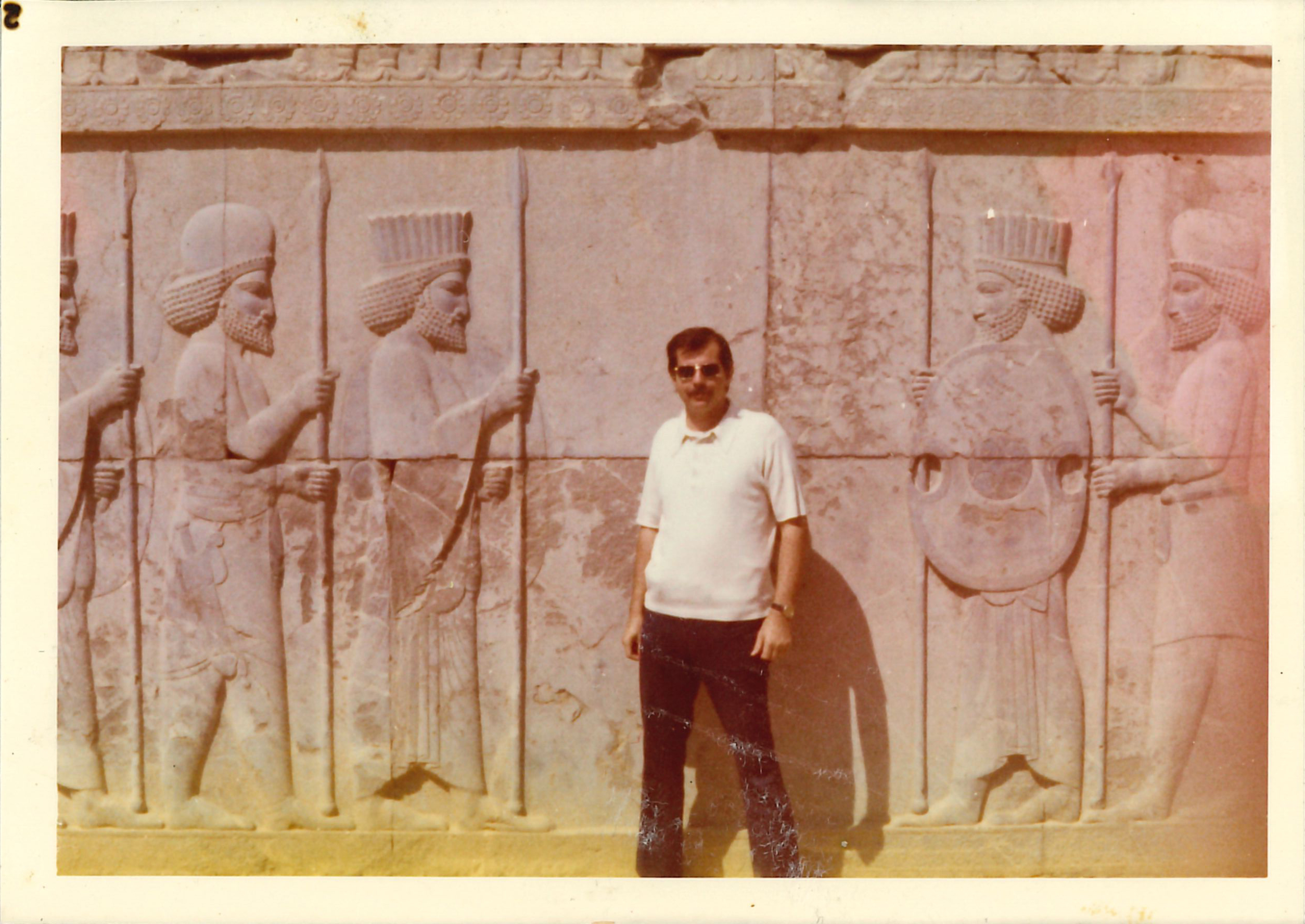

Orr believes the depth of his knowledge can be attributed to the many places he’s seen and the people with whom he has interacted. His career in the military and the offshore construction business led him all over the map, sparking his interest in ancient history of Mediterranean countries and motivating him to learn more about the world.

“All of my previous education had been in engineering because I was pretty good at it and it was a way to make a decent living,” Orr says. “But I was always on the outside looking in and wanted to expand my liberal arts knowledge and understanding of the world.”

He credits his military career with providing a good foundation for all that life has offered him, particularly in the way that it has enabled him to work with diverse groups of people, gain leadership and management skills, and learn how to function in a fairly restrictive environment. Orr’s service, he says, gave employers more confidence in his abilities, allowing him the autonomy to succeed in the workplace and eventually run his own business for 30 years.

He sees the Warrior Chorus as an opportunity to bring people together — soldiers, veterans and citizens, alike — to open-up dialogue and show the public that military service is worthwhile for the good of the people and the country. Much like his role as mayor, Orr hopes the chorus will welcome new voices and opinions. “As mayor, it was important to both respect and listen to people and encourage them to share their good ideas for the benefit of the city,” he says.

The classics, Orr thinks, offer a model for how people can participate and contribute to the common civic duty; and incorporating these works with real, modern stories of life and war told by those who have experienced it first hand, provides a unique platform to engage with classical texts while unveiling truths about the modern warrior experience.

“The classics are a reminder that conflict in the past and in our own contemporary time is real and seemingly unending despite our best efforts to live with others peacefully,” Orr says. “As humans we continue with some of the same fears and unknowns as these ancient stories relate.”

Life must be lived as play.

— Plato

The veterans in the chorus each recognize and appreciate the honesty and the authentic portrayal of the warrior-reality that is inscribed in each classical text. The texts, they say, expose and wrestle with reality in a way that modern literature avoids. It treats war as something that is expected, and service as a rightful duty.

“Greek society was both artistic and militaristic,” Pitchford says. “Often, the best playwrights and poets lived full lives in military service. So when someone like Aeschylus writes about Agamemnon, yes he is telling a mythological tale, but he uses that mythology to convey events which much of society experienced. In many ways Greek war literature was the way that the Greeks used to contemplate their participation in these extremely violent and ugly battles. This makes the classics a tremendous place to open the same conversations in a contemporary context.”

Having written and lectured extensively on human creative responses to war and violence for 25 years, Tom Palaima, the Robert M. Armstrong Centennial Professor of Classics, is the scholar advisor for the UT Austin Warrior Chorus.

“The ancient Athenian citizen soldiers communally shared the traumatic experiences of war in their tragedies that were written and performed by citizen soldiers for citizen soldiers during major public festivals,” says Palaima, who was named a MacArthur Fellow in 1985. In his role, he guides the veterans through classical iterations of life and war and encourages them to draw inspiration and encouragements from the timeless parallels that exist between their own stories and those in ancient texts.

The conversation often leads to an open exchange of ideas about anxieties, fears, struggles with mental illnesses, physical injuries and support systems, as the veterans relate to the classical themes and share stories of enlisting, serving and coming home. Palaima describes:

In Sophocles’ “Ajax,” the greatest Greek combat soldier after Achilles is driven to commit suicide when he is publicly overlooked and thereby humiliated in the process of awarding what would be considered in our terms a medal of honor. His words and actions make us feel his anger, his anguish, his sense of what was it all for. We too would want to lash out in anger and violence against the commanders who dishonored us in the same way. We too would feel trapped at the bottom of a very deep well and all alone, the same tunnel vision that drives so many of our soldiers and veterans to suicide.

In Homer’s “Odyssey,” Odysseus and his wife Penelope go through the unbearable process that all soldiers go through in coming back to their wives, partners, parents and families. The “Odyssey” raises the question of whether long absent soldiers, who have become very different persons during their time in military service, can ever get back home or successfully make new homes.

The “Iliad” reminds us again and again of the costs of war and how soldiers at some point will have to come to terms with the fact that the people against whom they are fighting are human beings with feelings, values and attachments to loved ones parallel to their own. Glaucus and Diomedes, a Trojan ally and a highly skilled Greek general respectively, recognize the longstanding ties their two families have had and make a ‘separate peace’ with one another right in the middle of all-out fighting on the plains of Troy.

The chorus, Palaima says, has taught to him the depths of feelings, strengths in facing challenges, joy in camaraderie and can-do cooperative spirit the veterans in the class possess.

Educating the mind without educating the heart is no education at all.

— Aristotle

“The veterans in the Warrior Chorus have worked hard to bring to the surface and then get across the many meaningful stories each of them carries inside. They are bringing to life and learning how to convey vividly what they saw and came to know when they were soldiers,” Palaima says. “It is terrific to watch them create the atmospherics that place me there where they once were and in some ways still are. Their generosity, honesty, sense of humor, ability to laugh at life’s absurdities, and lack of affectation make every meeting feel now like a warm family reunion.”

The veterans expose themselves by recounting memories from war and training, inviting others in to feel or at least become aware of what life is like in their boots. Their raw recollections depict what it’s like to go through training for the U.S. Marines, to be marched into a room filled with gas and then hear the orders barked to remove your mask. “How do you take a breath that will last ten minutes?” Palaima questions.

Or what it’s like to be assigned the mundane task of watching and guarding a road repair work team in Haditha, Iraq, late at night without knowing if you are a target for guerrilla warfare or simply an added stress in the day of an Iraqi mother held up by the roadwork, trying to get her children to school on time.

Or the moral battles army medics face when caring for prisoners who may have been directly responsible for the wounds and deaths of U.S. soldiers. “What is it like for a medic to stand outside their cells preparing to administer medical treatment and then to hear a young prisoner cry out, ‘I want my mother?’” Palaima asks.

These are the stories of today’s warriors, the stories Pitchford and Palaima encourage veterans to share weekly, and soon on a public stage, in a shared group effort to humanize the military and wartime, to eliminate misconceptions about soldiers and veterans, and to provide a window into their lives.

“My central pedagogical focus is on opening up space for memories to resurface and then helping the participants to embody those memories,” Pitchford says. “The goal is neither to be cathartic nor nostalgic, but to approach these individual experiences from honesty.”

Currently, two public performances scheduled for the spring 2017: March 5 at the Austin History Center and March 22 and 23 at the McCullough Theatre, where the group will perform in cooperation with the Warrior Chorus from the Aquila Theatre at NYU.

The Warrior Chorus at UT Austin is supported by the College of Liberal Arts and the College of Fine Arts, with additional support and facilitation provided by Texas Performing Arts campus and community engagement assistant director Judith Rhedin and program manager Cynthia Patterson.