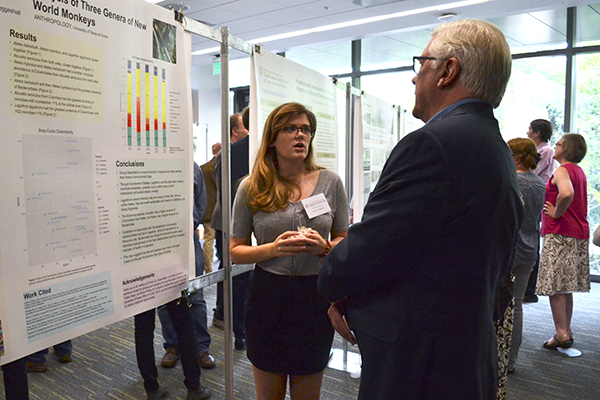

On April 19, 16 liberal arts student researchers presented their projects to faculty and staff members, college administrators and Dean Randy Diehl at the Dean’s Research Reception.

The annual event is a part of UT Austin’s Undergraduate Research Week, which is hosted by the Senate of College Councils and the Office of Undergraduate Research in the School of Undergraduate Studies. Colleges and organizations across campus coordinate events throughout the week to showcase the work of undergraduate student researchers.

Learn more about seven of the featured researchers in the story below.

Frontera Digital: Exploring Biometrics and Trans Lives Crossing the Border

Gabryella Desporte, a Latin American Studies senior from Austin, Texas, looked at the absence of literature pertaining to transgender migrants trying to cross the border. Desporte critiqued and explored how surveillance criminalizes queerness and trans bodies, and looked at how border control legislation coincides with trans migrant discrimination.

How would you describe your research project?

My research focuses on border surveillance technology, meaning everything from CCTVs to drones, to biometric information stored in Mexican citizens’ personal identification cards (CEDIs) and its relation to surveilling Mexican transgender migrants as they cross into the United States.

There is a lot of literature about border control surveillance and legislation that discusses the explicit use of surveillance technology, but I have found that there is an alarming lack of writing about what hardships and challenges transgender migrants face when they cross the border into the U.S. Although I did not have the opportunity to personally interview people for this project, I bridged the gap by looking at court cases that deal with transgender migrants seeking asylum in the U.S.

In the court cases I discuss in my research, these migrants are mostly looking to escape persecution from their families, police and gangs that either want to harm them or kill them because of their gender and sexuality. However, when they do apply for asylum in the United States, the question of how identification documents can be changed to represent themselves becomes a point of conflict, because it might still state on their ID that they are still their gender assigned at birth. With this project, I seek to explore the history of biometric surveillance (and how this influences racial profiling), and how identification documents have become a weapon against transgender migrants.

How did you decide on your topic?

I once read that Mexico has one of the highest rates of transphobia-related crimes in the world. This information moved me, especially because immigration and border control are issues that hit close to home for me. I was already doing research on border control surveillance out of personal interest, but I had a gut feeling that I needed to learn more about how this affects transgender migrants. I do not feel that their rights are being respected because of the stigma they face as a transgender person on top of being an undocumented migrant, and I wanted to learn more about ways I could personally help and empower them through research.

What element of research do you find most fascinating?

The element of surprise has been a consistent theme throughout my research. While looking at legislation and court cases that are relevant to the task at hand, I realized I wanted to explore more in-depth on some topics I hadn’t originally considered. I already have a set of notes that detail different ideas that I want to write about – it’s a regenerative process.

What effect could your research have?

I hope that this research can be used by both academics and those in law to help the transgender community both in and out of the United States. Their stories are consistently glazed over and are almost an afterthought, especially when they are migrants coming from another country. I hope that this research can be used to raise their voices and get people talking about queer and trans migrants’ rights.

Has this project impacted what you want to do after you graduate?

Absolutely. I am very interested in working in the nonprofit sector, especially in agencies that do outreach programs for kids as well as adults. I would like to work in an environment that empowers people and helps them find their voice, especially in the queer and trans community, where they face a lot of scrutiny just because of their gender and sexuality.

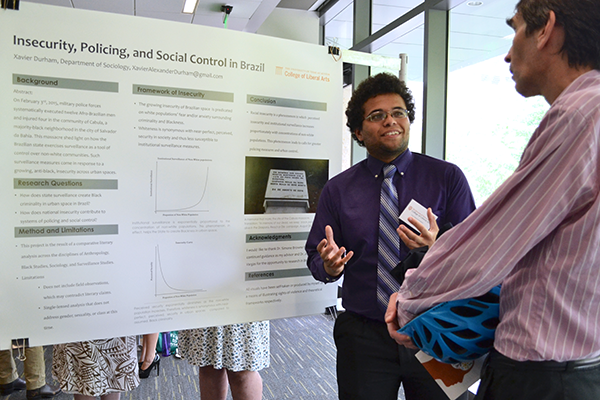

Insecurity, Policing and Social Control in Brazil

Xavier Durham, a sociology junior from San Antonio, analyzed the use of state surveillance to control and regulate Afro-Brazilian populations in Salvador, Bahia, namely in the form of policing.

How would you describe your research project?

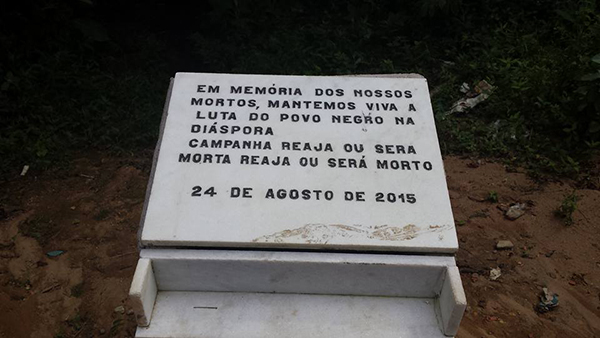

I am using the 2015 Cabula massacre in the community of Vila Moises as a case study for this analyses, as I feel it encapsulates the lived, violent experience of being black in Brazilian society in a tangible, yet devastating, manner.

On Feb. 3, 2015, 12 young Afro-Brazilian men were corralled and executed by military police and dressed up to look like a gang post-mortem. All the officers were exonerated, but there is a current push to have a federal investigation of the case and receive justice for the young men who were lost. My end goal is to find ways in which the Afro-Brazilian population in Salvador can resist the State’s gaze and further their campaign for collective liberation.

How did you decide on your topic?

In the summer of 2016, I had the opportunity to study abroad under a faculty-led program, headed by Dr. João H. Costa Vargas (African & African Diaspora Studies, anthropology), in Rio de Janeiro. During this trip, I traveled to Salvador, Bahia, and visited the site itself. The immense emotional pressure remained with me long after. I wanted to do something that could help, rather than simply making a career off of others’ pain and suffering.

How did you conduct your research?

I conducted my research through a theoretical lens, in which I compared literature across sociology, anthropology, black studies, and surveillance studies to have a tighter grip on the frameworks in which power, race and statutory interpolation play into the ability of the state to watch Afro-Brazilians.

What element of your research do you find most fascinating?

The most interesting component of my project is that little work has been done to examine the role of surveillance in Brazilian society, specifically theory.

However, when I examine North American-centric/Eurocentric theories concerning surveillance and control, I find that there are marked similarities between social phenomenon across civilizations. This trend allows me to proceed with a bit less caution, because theories centered in the United States, Canada and Europe seem to also manifest in Brazil thus far without being in conversation, save for phenomenon such as the spread of CCTV cameras.

What effect could this research have?

While I am only a life-long student of Brazilian culture and will never experience the life of an Afro-Brazilian individual, I have a strong feeling that my research will help to expand critical surveillance studies to the Global South. Furthermore, my research will work to curb police brutality in Afro-Brazilian communities even if it surpasses my lifetime. However, this research must be a continuous process of fighting against systems of oppression and using my privileged positions to speak up where others’ voices are silenced or excluded.

I am a militant researcher who is working toward the greater liberation of the peoples across the diaspora. This instance of violence is not new, nor will it be the last within black communities. However, it is up to our generation to fight these injustices and be willing to recognize our own faults, prejudices and positionality in the global context.

Has this project impacted what you want to do after you graduate?

After this research project, I am more sure than ever that I want to go to graduate school with the intention of becoming a professor. I want to expand the critical dimensions of sociology in my respective departments and cultivate a new generation of critical thinkers who do not simply accept what they are taught, even if it’s my own readings. I feel that academia will be an effective platform to globalize student education and truly understand the reach of human rights and social justice in areas outside of our hermetically sealed bubble known as the United States.

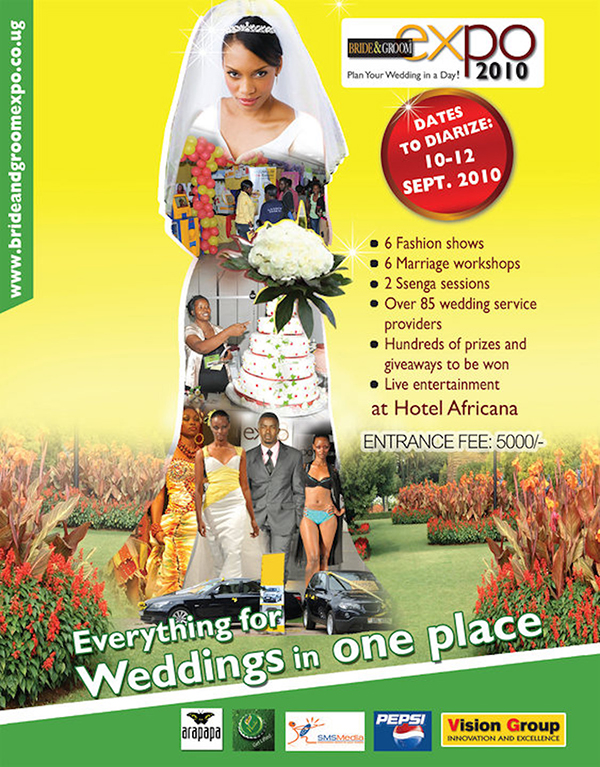

“Look What the Bride Has Got On!” A Visual Discourse Analysis of Uganda’s Wedding Industry

Annie Elledge, an international relations & global studies and government junior from Austin, Texas, researched the Ugandan wedding industry as a site where the country’s growing middle class increasingly participates in luxury consumption.

How would you describe your research project?

I particularly focus on the ideals of gender, race, class and sexuality that are underscored in images of Uganda’s wedding industry. The goal of this project is to underscore how Ugandan fashion designers and consumers, particularly women, actively participate in the wedding industry to highlight the ways in which these individuals contest and conform to idealized notions of Ugandan femininity.

How did you decide on your topic?

I have always been interested in studying ideals of beauty and gender, so when I found (geography and the environment professor) Dr. Caroline Faria’s project on the beauty and hair trade between Uganda and Dubai, I was immediately interested.

Within her larger project, I selected an analysis of Uganda’s wedding industry because I wanted to learn more about the industry itself and the experiences of people who participate and perpetuate this industry. Additionally, I wanted to research an industry that many people trivialize; for me, it is important to highlight how spaces, like the wedding, can reveal important insights into conceptions of nationalism and ideals of beauty.

How did you conduct your research?

Over this past academic year, I have conducted a visual discourse analysis of Uganda’s wedding industry by analyzing over 2,000 images from 20 years of fashion and beauty coverage in the leading newspaper, The New Vision, and from the Bride and Groom Expo collected by Dr. Faria and graduate student Dominica Whitesell during their time in Kampala, Uganda. I observed the subjects of the images, their positioning and what was absent in the images in order to analyze the content of the images and the role they play within Uganda’s wedding industry.

What element of your research do you find most fascinating?

The most fascinating part of the research was learning about the fashion industry in Uganda. Ugandan designers, like Sylvia Owori and Gloria Wavamunno, create fashions that speak to a uniquely Ugandan identity while also contextualizing those designs within Uganda’s geopolitical and geoeconomic positioning. I think it is important to highlight designers, like the women I mentioned, because their work contests ideas of African passivity. Instead, their designs underscore the ways in which Africans, and in this case Ugandans, are active participants in forces of globalization and neoliberalism.

What effect could this research have?

The most important part of this research is to contest ideas of African passivity and the trivialized nature of feminine spaces. By highlighting the ways in which Ugandans, particularly women, actively participate in trade and consumption of luxury industries, like the wedding industry, I contest ideas that Africans are passive recipients of globalization and neoliberal policies.

Through this research, I hope to underscore the ways in which individuals intimately experience these phenomena and how they use fashion or other modes to navigate them. Additionally, I think this research can highlight the importance of studying spaces that are traditionally trivialized. Often times, spaces like the wedding or the beauty pageant are written off because of how they are feminized. I think this research can add to a growing body of work that legitimizes these spaces and studies the ways in which these spaces reveal important ideas about a society and its people.

Has this project impacted what you want to do after you graduate?

This project has provided me with insight into academia and has greatly influenced my decision to pursue a doctorate in geography. I hope to focus my post-undergraduate work on beauty and nationalisms in Latin America, specifically Central America.

What’s next for your research?

In April, I traveled to Boston to present my research at the American Association of Geographers’ Annual Meeting and I will travel to Chapel Hill, North Carolina, this May to attend the Feminist Geography Conference to discuss the importance of building and sustaining feminist geography collectives.

Additionally, I will continue this research project with Dr. Faria and Dominica Whitesell this summer in Kampala, Uganda, where we will conduct the last part of the fieldwork for Dr. Faria’s National Science Foundation-funded project. I am incredibly excited for the opportunity to travel and conduct research, which will inform my senior honor’s thesis.

Prostitutes or Laborers: Sex, Work & Rights in India

enakshi ganguly is a humanities and government senior from Missouri City, Texas, whose research seeks to historicize sex work, in its many layers, as well as a counter-perspective on sex work in India through the political activism of sex workers in Sonagachi, Kolkata.

How would you describe your research project?

My work focuses on sex workers in Kolkata who are mobilizing for worker rights.

Currently, sex workers are, what I call, working within the “veil of domesticity,” so though they are laborers who are earning money, because they are doing so in the informal labor market, they are seen as housewives, not as workers. This disables them from accessing protection from the state, holding police accountable for the violence they perpetrate and establishing their own terms in their workspace.

The research itself examines the nation state’s rhetoric around sex work and interrogates respectability politics and misogyny, while focusing on the unionization of sex workers in Kolkata and citing them as feminist producers of knowledge power.

How did you decide on your topic?

I remember watching the Kama Sutra, directed by Mira Nair, and wondering how odd it was that she made everyone speak English during a time when the sub-continent was still a free land. Later, I found out that the movie was banned from India because it was too explicit and sexual. How can a book written by an Indian for Indians be banned in India? It was very odd. I had so many questions about the gaps in our attitudes towards our very own sexualities and the way we express it. We have temples with erotic art and whole books written just about how to perfume the body when the moon enters the waning crescent phase versus the waxing crescent phase.

In the middle of all this wondering, I saw a very poorly told story about kids of sex workers in Kolkata. What really disgusted me was the flippant way the white director used the labor, hope and experiences of these children to cater to her own ideas of what their lives should look like. I began to see how, amidst all this confusion around sexuality, repression of various sexualities and disciplining of women’s sexualities, the sex worker was disenfranchised the most. Through this small thesis, I am only scratching the surface of what is a giant narrative around the sexual arts, feminine labor, (pre/post) colonial sexualities and notions of mainstream respectability in India.

How did you conduct your research?

To establish a strong theoretical framework, I thoroughly examined the works of South Asian scholars, such as Partha Chatterjee, and the work produced by sex workers from Kolkata, as they unionized under the banner of Dubar Mahila Samanwaya Committee (DMSC). I did so by seeking out interviews they did with organizations, such as Amnesty International, as well as watching documentaries wherein they speak about their efforts of unionization and mobilization, such as Tales of the Night Fairies, directed by Dr. Shohini Ghosh.

I also took from parts of Indian pop culture, such as from movies about misogyny and respectability politics like Bollywood’s 2016 film, PINK, and narratives about sex workers and how they are portrayed within the same tired trope of victim and damaged woman, through movies like Amar Prem and Umrao Jaan.

Who was your mentor for this project? How did they impact it?

Dr. Syed Akbar Hyder (Asian Studies) was my advisor throughout this past year. He gave me critical and insightful feedback while I wrote and edited, and provided emotional and intellectual support when I needed it. Without him, I don’t think I would have finished my work.

What element of your research do you find most fascinating?

I think citing sex workers as knowledge producers and narrators of their own story is powerful and made me feel like the work I was doing was worthwhile. So often, third world women are not acknowledged as owners of their own stories, but rather, as objects to be paraded and shown. To be able to make space for women’s voices, for their work and efforts to take center stage, was exciting for me.

What effect could this research have?

This project is so vital to the world, especially right now, because it deals with how society assigns value to women, and their bodies, depending on how they decide to use it. Somehow, despite what modernity has brought us in terms of easier access to technology, we are still living in a state that hyper-surveys and polices the bodies of women and restricts their ability to express their own sexualities, work ethics and self-worth. Though my work is rooted in India, I believe it speaks to all women across the world who are struggling to set their own terms in the public work space as well as the private space, such as the household and their very own bodies.

Has this project impacted what you want to do after you graduate?

I want to work with folks who have been trafficked in the United States. My thesis is on sex workers in Kolkata, and though there is an assumption that they are all trafficked, that is not the case. However, I do understand that sex trafficking is a very real, very serious issue that continues to affect people around the world. As a way to extend my work, and complete it outside of my thesis, I want to work with those who have been trafficked in any capacity.

I will also apply for graduate school to earn my Ph.D. in South Asian studies, women & gender studies, and perhaps, ethnography.

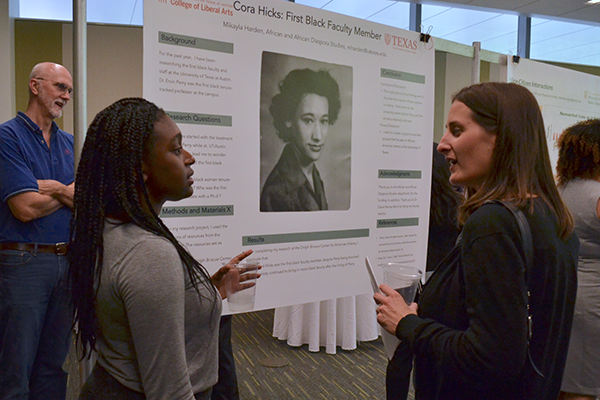

Cora Eiland Hicks: First Black Faculty Member

Mikayla Harden, a government and African & African Diaspora Studies honors junior from Crossett, Arkansas, by way of Houston, studied how the history of black female academics at The University of Texas at Austin has been largely erased from public memory.

How would you describe your research project?

I am researching the first black faculty and staff at The University of Texas at Austin. The history given by the University overlooks the role of black women in academia.

Despite Dr. Ervin Perry being honored as the first black professor and faculty member at UT Austin, he is only the first black tenure-track professor at the university. According to The Daily Texan’s archival newpapers, Cora Eiland Hicks was hired before Perry.

How did you decide on your topic?

In (history professor) Dr. Laurie Green’s civil rights in perspective course, we talked about integration on the Forty Acres. I really enjoyed looking into the topic. Therefore, I turned the project into my honors thesis.

How did you conduct your research?

I visit the archival materials in the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History. In addition, I use the oral histories from former students of the university.

Who was your mentor on this project? How did they impact it?

Dr. Daina Berry (history, African & African Diaspora Studies, women’s and gender studies). She has guided me for the past two years on multiple research projects. Everything I know about the field came from her sharing knowledge and giving advice. I hope my career follows her footsteps.

What element of your research do you find most fascinating?

I love hearing the different stories and experiences from former students.

What effect could this research have?

I really want people to discuss and bring more attention to the role of black women in academia and honor them.

Has this project impacted what you want to do after you graduate?

Yes, I want to be a history professor.

What’s next for your research?

I will be spending my summer at Brown University researching under historian Dr. Emily Owens.

An Undue Emotional Burden: Abortion Stigma Among Latinas in the Rio Grande Valley

Abigail Newell, a sociology and liberal arts honors senior from Pittsburgh, analyzed Texas Latinas’ experiences of abortion stigma in her research and examined possible causes for the stigma.

How would you describe your research project?

The project attempts to understand possible cultural factors that contribute to Latinas’ experiences of abortion stigma in the Rio Grande Valley using the intersectional framework.

Through a case study of multiple reproductive justice nonprofits and in-depth interviews with community leaders in the Rio Grande Valley, findings demonstrate that while legal abortions are safe, abortion stigma and its implications are clearly harmful. Latinas do not necessarily experience more stigma due to “traditional Latino/a culture.” However, the implications of abortion stigma are more serious for this population, due to their significant lack of reproductive healthcare. Instead, policy that marginalizes women and their bodily autonomy causes abortion stigma and perpetuates the patriarchal hierarchy.

The study provides evidence that contradicts previous research labeling Latino/as as largely anti-choice. Finally, the results of the study suggest that open discussion, storytelling and personal connections help to reduce abortion stigma and its damaging effects.

How did you decide on your topic?

I became an active member of the reproductive justice activist community after moving to Texas. In Pennsylvania, I took my reproductive rights for granted. Access to reproductive care is significantly stratified along racial/ethnic and socioeconomic lines in Texas. Though research analyzes the physiological health disparities that arise out of this inequity in access to care, little research seeks to understand the psychological effects of restricted abortion access and stigma. My project seeks to fill this gap in research, but most importantly, it seeks to provide a platform for the stories of Latinas in the Rio Grande Valley, whose voices are often lost in vast quantitative studies. Interviews provide a nuanced understanding of how these women are suffering from stigma and possible interventions to alleviate this stigma.

How did you conduct your research?

The research project consists of a case study of three reproductive justice nonprofits and in-depth interviews with reproductive justice leaders in the Rio Grande Valley community.

Who mentored you on this project?

Dr. Sheldon-Ekland Olsen (sociology) was my primary advisor and Dr. Penny Green (sociology) was my secondary advisor. Both provided sage guidance about the sudden twists and turns of research. Both encouraged my creativity, changing directions, and passion. Most importantly, they created a community of support that picked me up every time I fell down. I cannot thank either of them enough.

What element of your research do you find most fascinating?

The results from my interviews demonstrated the power of misogyny and sexism in legislation that restricts access to abortion. Sexism is not unique to any culture; patriarchy is still the default system in almost every place in the world. The implications of gender inequity in policy perpetuate the oppression and dominance of women, especially women of color.

What effect could this research have?

The results of this study call for statewide policy reform in order to equalize access to abortion care. Furthermore, policymakers should invest in long-acting, accessible and affordable contraception and comprehensive sex education in public schools to reduce abortion rates.

To reduce abortion stigma, reproductive justice nonprofits should continue using storytelling as a method to reduce stigma. Comprehensive sex education will also increase discussion about abortion in order to normalize the procedure and alleviate stigma.

Has this project impacted what you want to do after you graduate?

The project inspired me to pursue a Ph.D. in sociology to continue studying women’s health disparities, intersectionality and immigration. Ideally, my future research will inform public health policy.

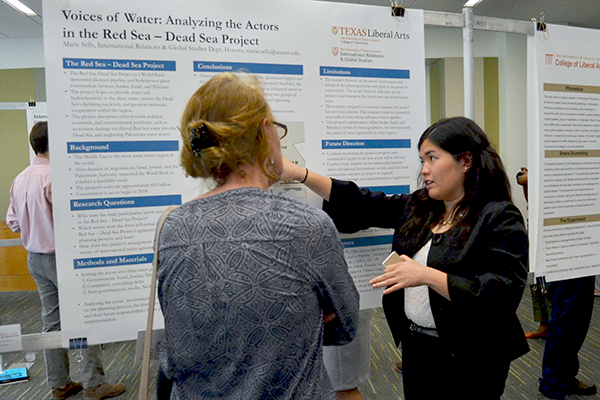

The Voices of Water: Analyzing the Actors in the Red Sea–Dead Sea Project

Marie Sells, an international relations & global studies and liberal arts honors senior from Schertz, Texas, used her research to explore how the governments, companies and nongovernmental organizations planned the Red Sea–Dead Sea agreement, and which of these entities was the most influential in the process.

How would you describe your research project?

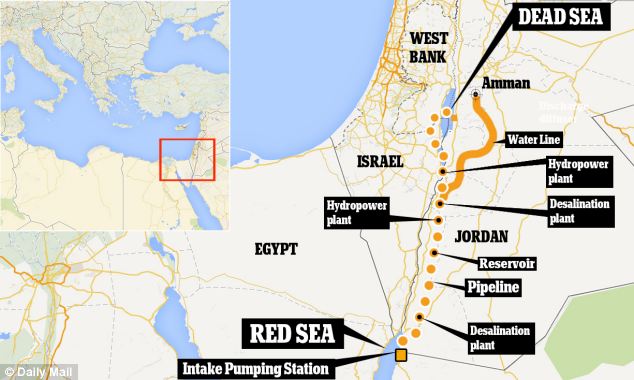

The Red Sea–Dead Sea Project is a World Bank-sponsored planned pipeline between Jordan, Israel and Palestine that seeks to provide water and hydroelectricity and restore the Dead Sea’s declining sea levels. The project’s construction is set to begin in 2018, with projected costs approximating $10 billion.

Through the project’s agreements, I am researching how the governments, companies and nongovernmental organizations planned the agreement, and which of these entities was the most influential in the planning process.

How did you decide on your topic?

I learned about this project when I was interning last summer at the U.S. Department of State in Washington, D.C. I was working in the Office of Levant Affairs, the office that focuses on Lebanese, Jordanian and Syrian affairs. I worked mostly on Jordan and Lebanon, and came across this project. I thought it was one of the most interesting things that was happening in Jordan, so I read articles and books in the State Department’s library on this project and the concept of international water development projects and agreements happening in the Middle East.

The Middle East’s work on water is not a topic that American media regularly covers. Yet, water is an important issue in this region because it’s the most water-scarce area on Earth, and the added pressures of population growth, regional conflicts and climate change will greatly affect their water quantity and access. The fact that this project is an example of how the region is working on its issues is something I became interested in, so I decided to research the project for a thesis after I left the State Department.

How did you conduct your research?

Finding research material for this project was more difficult than I expected. I had some articles that I collected from the State Department’s library, but I had to get the project’s feasibility studies and government documents through UT’s interlibrary loan system. Some of the documents took a long time to obtain because they were only located in only one library in the world, but I was still able to most of them. I used the World Bank’s Red Sea–Dead Sea Conveyance Study Program a lot because they have their initial and final report drafts and transcripts of the meetings between the different actors posted online.

I also used the Jordanian, Israeli and Palestinian governments’ websites and research articles from the three states’ universities and environmental studies centers. Lastly, I used media articles from this region or abroad to see what people in these states or outside of the region thought about the project and its progress.

Who mentored you on this project?

I had a lot of people help me with this project. First, my Jordan desk colleagues from the State Department helped me connect with other State Department offices and World Bank officials to get more information on the project’s agreements process.

My thesis supervisor and director of the International Relations and Global Studies Department, Dr. Michael Anderson, taught me how to organize the narrative and flow of my research findings and how to communicate the significance of this research to a broader audience.

What effect could this research have?

I hope this research will encourage more people to think about how water issues start at the local level and consider how international water agreements comprise of negotiations between all sorts of constituents instead of negotiations only between government entities.

I would like everyone to think about water issues that are happening in their own communities and take time to explore what their city councils and local companies and organizations are doing about them to see what they could do to address water awareness in their own lives.

Has this project impacted what you want to do after you graduate?

The project has inspired me to study natural resource management for graduate school instead of focusing on international affairs alone.

However, I am not going to be going to graduate school immediately after graduation because I want to learn more about what is happening in the realms of natural resource management, economic growth, security and other political affairs from working in different jobs before going to graduate school.

To learn more about research in the College of Liberal Arts, visit the Frontiers research page.