If you search “women in the 1920s” in Google Images, what you get are a few photos of women working or protesting, but many more photos of sexually liberated flappers — at the beach, on the town, or dancing the night away at some speakeasy. The 1920s look like one big party.

But the decade wasn’t for many people. After women in the U.S. won the right to vote in 1920 and saw their numbers rise in the workplace, gains in political or economic power for women were slow to come, if at all. And while wearing bobbed hair and smoking in public signaled a desire for social change, it wasn’t enough for Ruth Epperson Kennell and hundreds of other young American women in the 1920s and ’30s who believed that real change and real equality could only be found in a place dedicated to the public good rather than individual profit.

That place, so they believed, was the Soviet Union.

“We don’t usually think of Moscow as a popular destination for single American women of the twentieth century,” writes Julia Mickenberg, associate professor of American studies, in her new book, American Girls in Red Russia: Chasing the Soviet Dream. “A mythology surrounds the ‘lost generation’ of Americans who sought out Paris in the 1920s, but few know about the exodus of thousands of Americans — former Paris expats among them — to the ‘red Jerusalem’… Even fewer are aware of ‘red Russia’s’ particular pull for ‘American girls,’ or, more accurately, independent, educated and adventurous ‘new women.’”

Kennell was among these “new women” who inspired Mickenberg to write the book.

“I was thinking about doing an article on pro-Soviet children’s literature, and she was a children’s book writer,” says Mickenberg, who during the course of her research read Theodore Dreiser’s sketch of Kennell (under the pseudonym “Ernita”) in his two-volume A Gallery of Women.

“It was an amazing piece, this story of her moving to a utopian colony in Siberia — she leaves her 18-month-old child behind with her mother-in-law, later dumps her husband and falls in love with another guy,” says Mickenberg. “She wanted to escape the domestic drudgery at home — wanted to be there in Siberia as a worker and not as a wife.”

In hindsight we know about the famines, purges and later the paranoia-fueled terror of those first decades of Bolshevik rule, so today it might seem silly or naïve for these young women to flee the relative comforts of home for the hardships of Soviet life. Unfortunately, many scholars have simply dismissed these women and their male counterparts as deluded, and there has been little scholarship looking specifically at women as a group.

University of Chicago Press, May 2017

By Julia L. Mickenberg, associate professor, Department of American Studies

Mickenberg doesn’t necessarily support the choices these women made, but simply dismissing them as delusional “minimizes the complex nature of their motivations, their desires and their experiences.” Indeed, nearly a century ago many journalists, writers, artists and social reformers looked to revolutionary Russia as a promised land.

“There is historical amnesia about the massive number of people who were really deeply interested,” she says. “Of course it became a totalitarian, repressive, violent society (and had elements of these qualities from the beginning) — but if you look at the writing from the 1920s and ’30s, it also represented hope, excitement, optimism and possibility.”

There were a number of female writers such as Kennell who chronicled those heady times. Prominent among them was Anna Louise Strong, a strapping woman from the Nebraska plains who helped found the English-language Moscow News, a paper she said would be pro-Soviet but independent, serving the growing community of Americans living and working in the Soviet Union.

“[Strong] was an incredibly pathetic figure — she devotes so much of her life to promoting the Soviet Union, and then in the end gets arrested as a spy and expelled,” says Mickenberg. “The funny thing is I found her pathetic while also identifying with her at times because she worked so hard and wanted to be liked. I discovered that in fact many people disliked her because she was so pushy and unrelenting in her pro-Soviet rhetoric. Privately she was much more critical of all the problems she saw, but felt that enough people were exposing the negative things, and she ought to show all the good that was happening.”

The distance between what people think or write privately and what they say publicly was an aspect of the research Mickenberg found particularly interesting.

“I have a kind of voyeuristic relationship to archival research — I always like reading the unpublished stuff because I want to learn secrets and get into people’s lives and heads — I wanted to see the difference between what people would write in a diary or letter versus what they would publish,” she says. “I was very interested in this dynamic between the private and public expressions, why the difference and how people rationalized things and how this thing brought meaning to their lives.”

Mickenberg traveled to Moscow twice for the project, plunging into the byzantine process of archival research in Russia and learning enough Russian to “actually be in the archive and figure out what I needed to look at.” The depth and breadth of Mickenberg’s research is impressive, detailing the experiences of a cross-section of Americans who for idealistic or economic reasons — or both — joined up with the Soviet experiment.

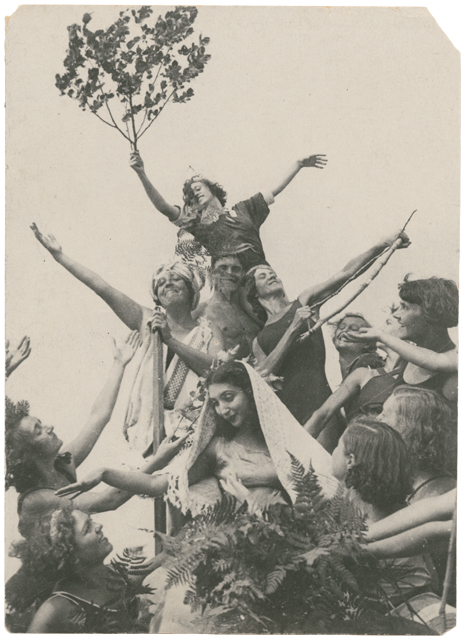

What is particularly striking is the idealism and optimism expressed by those early arrivers who witnessed the horrors of the civil war and famine of 1918-1921. Among them was dancer Isadora Duncan, who saw the carnage in biblical terms, declaring in 1921 that “Moscow is a miracle city, and the martyrdom submitted by Russia will be for the future that which the crucifixion was.”

Journalist Milly Bennett, who along with Kennell would later satirize the experiences of American “pilgrims” in the Soviet Union, nevertheless wrote: “The thing you have to do about Russia is what you do about any other ‘faith.’ You set your heart to know they are right … And then, when you see things that shudder your bones, you close your eyes and say … ‘facts are not important.’”

“I think the suffering was part of the appeal,” says Mickenberg of the intellectual class who went to the Soviet Union instead joining the Lost Generation in Paris. “They were not going to sit in the Paris cafés and drink and complain — they were going to get down in the dirt and be part of this building the world anew.” In a way, suffering could be endured, even celebrated if placed in the context of history.

Strong, who spent her first years in Russia recovering from typhus, was obsessed with the idea of painting Soviet life in a positive light for American readers. Mickenberg writes that although she had seen nothing but devastation, Strong later reflected that “not for a moment did it occur to me that I could permanently leave this country, this chaos in which a world was being born. It was the chaos that drew me, and the sight of creators of chaos. I intended to have a share in this creation … America was no longer the world’s pioneer.”

Kennell arrived in 1922 at the start of the New Economic Policy (which reinstituted limited private trade, relaxed war restrictions and a more open cultural climate), going to work at the mostly American-organized Autonomous Industrial Colony of Kuzbas in Siberia. Mickenberg writes that for Kennell it was “a two-year experiment with socialized housework, collective responsibilities and a very different moral code (that) shaped the rest of her life.” She was not alone. Between 1923 and 1926, foreigners organized nine agricultural and 26 industrial collectives, 24 of which were primarily made up of Americans.

Many more Americans came to the Soviet Union during its first Five-Year Plan (1928–1932). With the onset of the Great Depression, engineers, laborers and autoworkers were actively recruited by the Bolsheviks to address labor shortages caused by their massive industrialization plan. Mickenberg writes that at the height of industrial development, “approximately 35,000 foreign workers and their families were living in the Soviet Union. A significant proportion of these were American.” Those years might have been good for some Americans seeking work, but they were also years of unspeakable hardship for many Soviet citizens — historians estimate that between 1929 and 1934 as many as 14.5 million people died from forced collectivization and famine.

Nevertheless, the lure of the Soviet Union continued to attract Americans, including the likes of suffragette Alice Stone Blackwell, reformer Lillian Wald and African American actress Frances E. Williams who, Mickenberg writes, “came to Moscow in 1934 in search of professional opportunity, adventure and a chance to experience life in a land that had supposedly eliminated racism.”

“Most African Americans went there because it was a place where supposedly racism had been made illegal,” says Mickenberg. “The Scottsboro (Boys) case figured prominently into that story because it became such a cause célèbre of the Communist Party and Soviet Union.”

However, it was much easier to idealize the Soviet Union if you didn’t have to live or stay there, says Mickenberg, and it “was almost impossible to go on idealizing if you lived there.” She writes that “visitors experienced difficult conditions, but they were far better than those endured by Soviet citizens. And visitors, if they did not become Soviet citizens, usually had the security of knowing they could leave.”

Young women like Ruth Epperson Kennell “were not going to sit in the Paris cafés and drink and complain —they were going to get down in the dirt and be part of this building the world anew.”

Julia Mickenberg

Unfortunately, that was not the case for young Mary Leder, who emigrated from Los Angeles to the Russian Far East in 1931 with her idealistic parents, who were attracted to the secular Jewish homeland Stalin promised to build there. When she found life in the remote outpost of Birobidjian unbearable, she went on her own to Moscow. Realizing she had forgotten her passport, she asked her father to send it by registered mail, but it never arrived. Needing to find work, she took Soviet citizenship, but when her parents decided to leave after two years, she was forbidden to join them. She remained in the Soviet Union until 1964.

Mickenberg writes that other Western women who became Soviet citizens were even less fortunate than Leder. They ended up in prison camps or dead. A Stalinist purge in the late 1930s led to the imprisonment or death of more than a million Soviet citizens. Several of the staff of Moscow News, ones Strong believed were among the hardest workers and the most dedicated to the Party, were arrested and killed. A former Detroit autoworker who spent 44 years in the Soviet Union before returning to the U.S. said he knew a number of African Americans who had become Soviet citizens, but within seven years they all had disappeared, sent to labor camps or shot.

In Ruth Kennell’s own Kuzbas colony, 29 settlers who stayed in the Soviet Union wound up in labor camps, and 22 of them died there. Mickenberg writes that the Great Terror “brought serious criticism from many people in the United States, including leftist intellectuals frustrated with what they perceived as a Stalinist hijacking of the Left.”

Some, however, remained more or less loyal to the cause, including Kennell. According to Mickenberg, Kennell admitted in her later writings that “the Soviet system remained ill equipped to truly liberate women from their domestic duties: ‘Women are not deserting their firesides to do labor on an equal basis with men — they simply handle two jobs instead of one.’” But once safely out of the country, Kennell also “found it easier to be pro-Soviet.”

In 1968, Kennell wrote a book about Dreiser and the Soviet Union, and in the preface she addressed members of the New Left. “This younger generation who thought they had invented radicalism and were critical of the Soviets — she hoped this new generation of radicals would understand what their (the Old Left’s) attraction was to the Soviet Union,” says Mickenberg.

In the end, she says these stories speak to the endurance of “humankind’s struggle for satisfying work or egalitarian relationships or a more just society, a way for women to be mothers and also have careers, how to balance work and home, how to live a meaningful life. Those things don’t go away, nor does our desire for human perfectibility, or our desire for having some magic or system that is going to make it work.”