I’ll have to admit that I was a bit perplexed when I heard linguistic anthropologist Elizabeth Keating say, “There is a very strong preference for agreement in conversation in the U.S.”

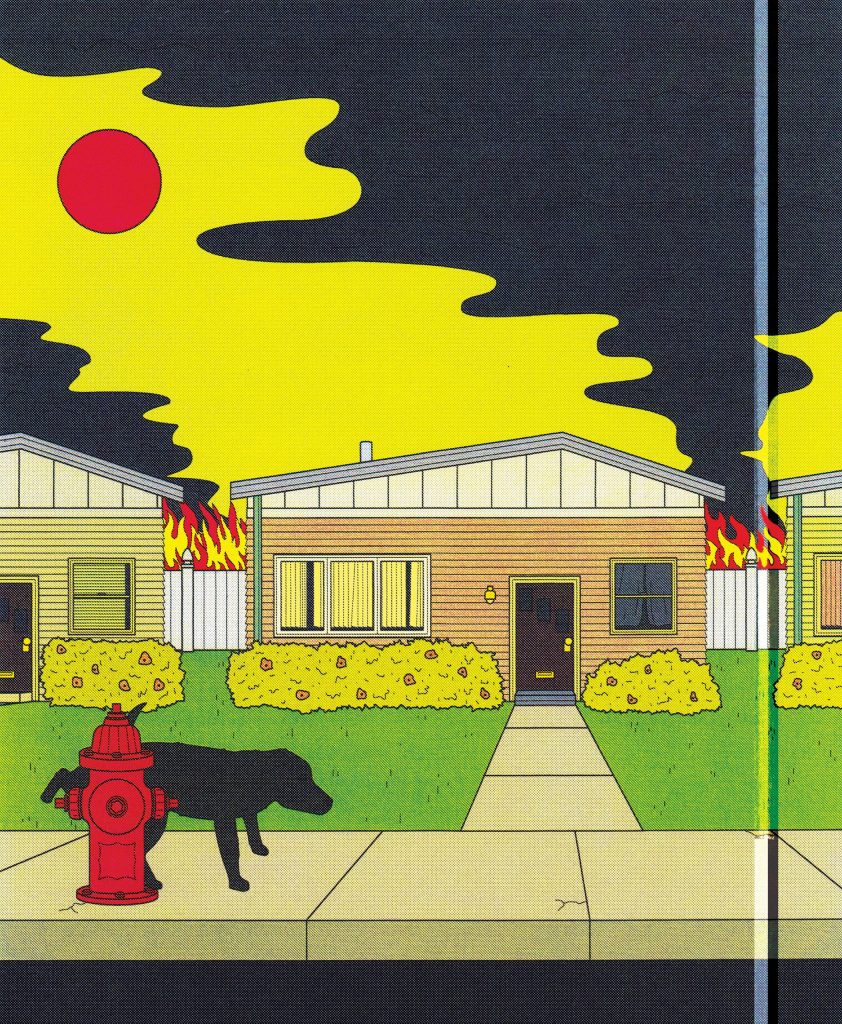

I couldn’t believe my ears — even the Pew Research Center pegged political polarization as the defining feature of modern U.S. politics. And it’s easy to see why: Pressing issues are painted with a broad red or blue brush; social media has regressed into a soap box for dogma and dislikes; and more energy is put into building walls around our ideological silos than challenging our beliefs through dialogue with someone who thinks differently.

“One of the things that makes arguments so uncomfortable is our preference for agreement — preference meaning it’s what people do easily and quickly,” Keating says. “People have a tendency to stay within their own political group and don’t often encounter a lot of argument about their political position, but in this election cycle it’s been more of a public debate.”

Our anxieties about the best way forward for America are fomenting disagreement, which arises when we can’t affiliate in our assessment on the way the world is, Keating explains, adding that much work goes into trying to balance or “negotiate” this harmony in conversation, especially when topics are high risk.

“It’s perhaps a sign that the negotiation of what America is is taking a bit more work than usual,” she says. “That’s a pretty high-stakes negotiation considering the problems we are facing. And I think the action of planning the future, of planning out our collaboration and what we are going to do, is becoming pretty urgent for people.”

Language as Action

Keating, a professor of anthropology at The University of Texas at Austin, studies culture and communication to better understand language as a tool for creating and maintaining global societies. Her most recent book, Words Matter: Communicating Effectively in the New Global Office, takes a close look at successful and unsuccessful language practices in the global work place and introduces the “Communication Plus Model,” which, she explains, is much more effective than the one many of us use and recognize. Don’t feel bad. She assures that “a lot of it is habitual, and we aren’t good analysts of our own practices.”

The most common practice is referred to as the Conduit Model: One person transmits information to another person like a one-way tube that alternates depending on who has the information. “The problem with this is that it isn’t accurate at all,” Keating says, adding that we have to pay more attention to what we are trying to do within our conversations.

“You have to think of language as action, language as a tool for negotiation,” she says. “What is the underlying action that someone is trying to do? We’re always using language to do something together; we’re trying to get some action done in the world.”

This inspired me, and I took to Facebook to see the underlying goals or actions my friends have when approaching an argument: “What’s your goal?” I asked.

“To win,” some said, and others more civilly phrased, “to challenge the other side,” “make them think,” “defend my stance,” or “offer a different perspective.”

These are no doubt goals of debate, but they miss the mark on negotiation. In order for a negotiation to take place, more emphasis has to be put on the hearer, who “is much more important than people give credit to and that impacts the problem with arguing,” Keating says.

Perhaps the people who responded: “find common ground,” “understand the other side and find ways to connect,” “share information with the goal of broadening my and my opponent’s understanding of the issue,” or “to discover truth,” hit closer to the negotiation mark.

Rise of Relativism

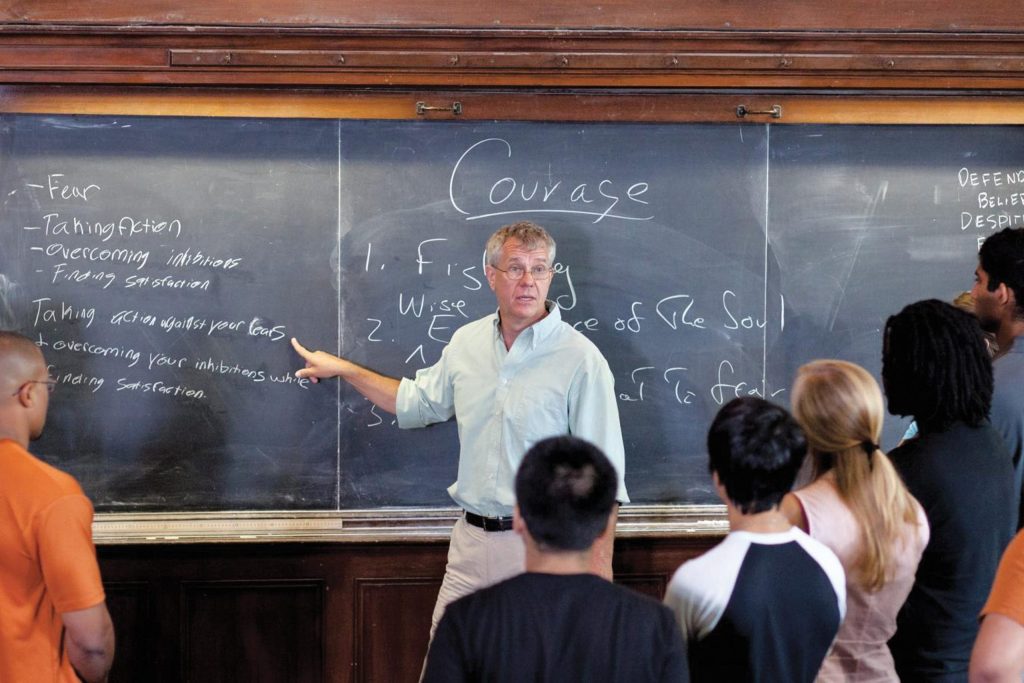

“You have to have a sense that there is such a thing as the truth. If you don’t think there’s a goal of truth that you’re after, then there is nothing to get to,” says philosophy professor Daniel Bonevac, who notes that one of the biggest challenges in his classroom has been to overcome what appears to be a rise of relativism and a fear of stepping on toes.

“More and more I notice students are holding onto this supposedly sophisticated notion that there is no truth; there’s just your perspective and my perspective,” he says. “If that’s your attitude, then what’s the point of discussion?”

Bonevac worries that too many issues are becoming a matter of taste, that our dialogues have evolved into postmodern debate about whose current bias is more legitimate, rather than approaching conversations with the sense that there’s a truth to be achieved. This tendency “corrodes the culture” and cuts off discussion before it begins. “Philosophy depends on being able to engage in dialogue about things,” he says.

Bonevac suggests Plato as an example, “especially his earlier dialogues when we get the sense that Socrates is really grappling with a question that he doesn’t know the answer to. So other people are making proposals, and he’s taking them seriously.

“You not only see Socrates making all of these moves, but you get to see the moral of that, reflect on that, and understand how to think. There’s something very constructive about it.”

Socratic dialogues can train people how to think, how to argue for or against something, how to analyze a problem from both sides, and most importantly, how to ask the right questions, he says.

“It shows that it’s possible to come to some kind of agreement, where you realize everyone is partly right and that they need to combine their thoughts and do something that takes it all into account,” Bonevac says.

Note the words “partly right.” To get his students engaged in dialogue and shake their held notion of relativism, Bonevac introduces them to the idea of perspectivism, coined by José Ortega y Gasset in The Modern Theme, which grants that while everyone has his or her own point of view, we are each seeing incomplete versions of the whole truth.

He uses the example of people looking at a landscape from different points around it: “Maybe you see a house, and from my angle, I see trees. And someone flying in a helicopter overhead sees a pond — but there’s a truth about the landscape.

“What’s beautiful about it is that you get the sense that if you move around, you can see more,” Bonevac says. “That helps students see that of course there are things they don’t know and perspectives they hadn’t considered. They get the sense that they can ‘move around’ perspectives by reading literature and philosophy, by traveling or by simply talking to people.”

Loaded Trigger

But dialoguing more contentious matters can be tough for students to navigate. “When issues get too scary, students retreat because they are afraid that certain perspectives are not going to be considered legitimate,” Bonevac says. “It’s so unclear to anybody where the boundaries are, and I think that’s what has changed a lot over the last couple of years.”

He wrestles with the modern idea of “triggering,” and how his students seem to shy away from difficult conversations, especially when topics such as abortion or affirmative action come up.

“You have to think of language as action, language as a tool for negotiation.”

Elizabeth Keating

That’s because “language is layered with social and cultural context,” Keating argues. “Every utterance that we create, every sentence we hear, has some memory. We are always picking out context from our memory, whatever someone says to us is already connected to our own history, and in that way language is never neutral.”

Triggering becomes an issue when a word or phrase activates a memory or past association in someone that the speaker might not have intended to spark, Keating says. And that’s where the “problematic concept” of political correctness rears its persnickety head, encouraging people to speak with less “loaded” language.

Words Matter: Communicating Effectively in the New Global Office

University of California Press, Oct. 2016

by Elizabeth Keating and Sirkka L. Jarvenpaa

“It’s something to strive for, to be inoffensive and avoid stereotyping or categorizing people,” Keating says. “A lot of times, people assume their background is just like everyone else’s and don’t understand how some people have had to encounter a different reality and experience.”

The U.S. has been called a “melting pot” of experiences, backgrounds, cultures and realities. We each have vastly different experiences depending on our socioeconomic status, where we grew up, the type of education we received, our religion and, according to classics professor Karl Galinsky, how leadership has influenced our communities.

“Memories are shaped by whoever is in power,” says Galinsky, who received the Max Planck Prize for International Cooperation for his studies in cultural memory. Keating adds that throughout history groups of people have been affected differently by U.S. policy. As a result, our memory and therefore our language continues to carry a lot of “cultural baggage.”

Let It Go

Although our memories and experiences shape our perspective, and our nation’s history has helped to build the ideologies we hold today, Galinsky argues that we can’t make any progress with modern arguments if we are too caught up in events that have already happened.

“People tend to go back and basically rewrite the past in light of the present, projecting all of these modern notions into it that were not necessarily there,” Galinsky says. “The past is constantly simplified too much or made into some sort of dogma, instead of making it a springboard for thinking about these issues and exploring them.”

Psychology professor Art Markman chimes in with a similar idea of how we tend to look abstractly on the past, particularly when it comes to controversial issues or politics. “We have this tendency to put a partisan lens on things that happened in the past, as well as things that are happening right now that shouldn’t be so divisive,” he says.

Rather than dwelling over a past event or framing it to adhere to some current political ideology, Galinsky and Markman suggest we get to the root of the problem, the causes and issues, and take what positive steps we can to improve matters and let go of the rest.

The Modern Theme (Classic Reprint)

Forgotten Books, Nov. 2016

by José Ortega y Gasset

Galinsky shares an example from ancient Athens after the atrocities of the Thirty Tyrants, when the Athenians restored their democracy and passed a law of general amnesty at the Council of the Areopagus that literally translates to “don’t remember the bad stuff.”

“I don’t want to sound like Elsa the Snow Queen, but ‘Let It Go,’” Galinsky says with a laugh, referring to a song from the 2013 movie Frozen.

Though the decree is rather extreme and not necessarily appropriate for the U.S. today, people can adapt their own Let It Go mantra as they form opinions about U.S. history, politics and contemporary issues. “Let it go if it simply blinds and challenges the future,” he asserts.

In this case, “the bad stuff” could be influenced by the rhetoric used by politicians and leaders to reflect on past and current legislation or issues. Take, for instance, the graduate program Human Dimensions of Organizations, where Markman presents the examples of Richard Nixon’s opening of relations with China in the early 1970s and of Jimmy Carter and the Camp David Accords a few years later. Though each president represents opposite sides of the political spectrum, both show how to negotiate with people and resolve disagreements with those “who previously had a real intractable disagreement.”

“I think by trying to, in this case, grapple with history in a way that makes the partisan element of it secondary helps people to realize they don’t have to look at everything in American politics through the lens of political parties that are associated with it,” Markman says. “You can leave that partisan lens behind and just try to understand it for the degree to which it was effective or not at some aspect of the human element of engaging in disputes.”

Dueling Conversations

Our arguments can’t go anywhere if people continue spatting out stances, facts and insults as if some third person is listening in to declare a winner, and aren’t open to engaging in a back-and-forth dialogue.

“Debates try to push two sides further apart,” Markman says. “Rather than trying to come to a mutual understanding of something, you’re trying to take the collection of the bits of information that are out there in the world and weave them together in a way that makes your point of view seem best and the other person’s seem worse.”

He adds that although the U.S. has an agreeable or neighborly culture, we have a tendency to be competitive to the point where conversations on competing views are handled, figuratively speaking, “as a fight to the death.”

“People begin to try and indoctrinate the other person rather than argue,” Galinsky says. “We’re witnessing the coarsening of discourse. What’s happened is the acceptance of the kind of discourse that basically denigrates, ridicules and puts the whole thing in the basest terms. Everything is dragged down to monosyllables.

“There are really no thoughtful arguments anymore. It’s one of the biggest tragedies. We have so many resources to inform ourselves across the spectrum, but people don’t want to do that. They want to be reconfirmed about their way of thinking. Propaganda doesn’t just come from the government.”

“More and more I notice students are holding onto this supposedly sophisticated notion that there is no truth; there’s just your perspective and my perspective. If that’s your attitude, then what’s the point of discussion?”

Daniel Bonevac

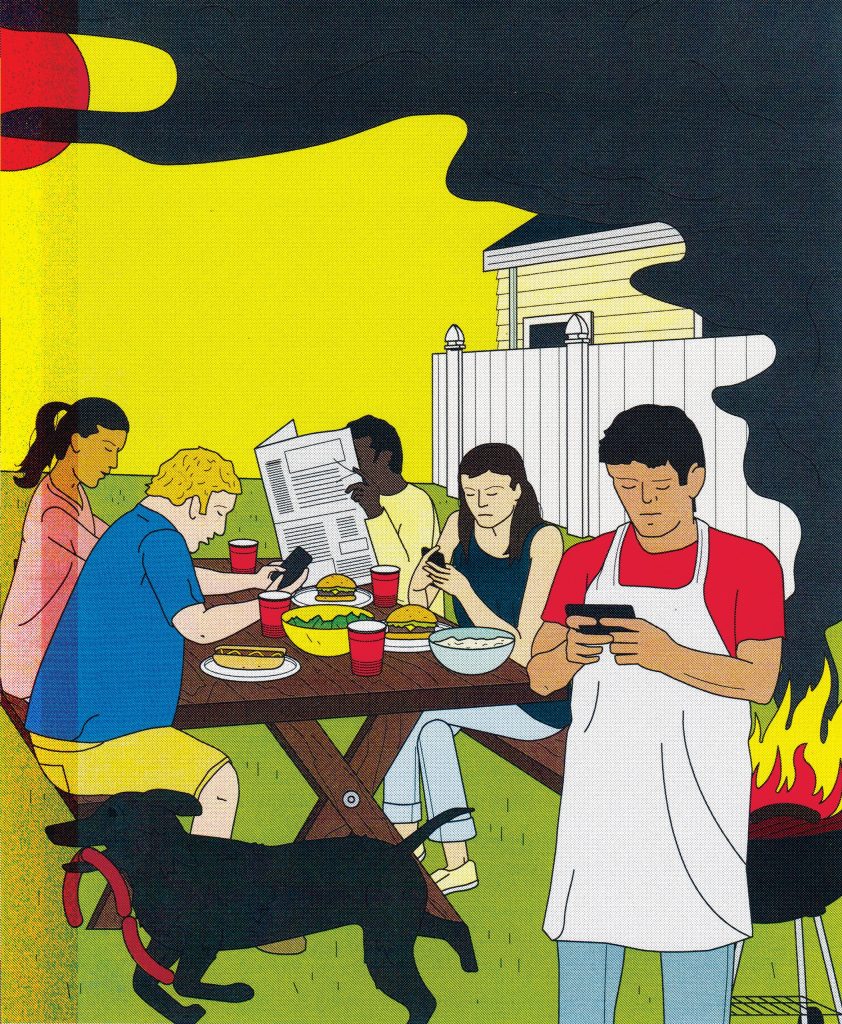

Now more than ever, it’s easy to pick and choose the information and news we consume. Sometimes, it even comes to us, with online marketing’s ability to target specific groups or individuals. It’s no wonder “fake news” has disrupted mainstream media. It’s part of our agreeable and cooperative tendencies to side with those who speak our language or share our ideas, Markman says, reiterating Keating’s claim of America’s agreeable conversational culture.

“We know that there are unpleasant conversations out there, and we don’t like to engage in them,” Markman says. “And the modern world gives us plenty of ways to avoid it.”

Social networks make it easier for us to hang out, at least virtually, with people we agree with, and the proliferation of newspapers, websites and video channels that conform to a certain ideology make it easier for us to engage with content that fits our existing worldview, he says.

“We don’t have to encounter much that goes beyond what we already believe, so we create our own little echo chambers, and that makes it harder and harder to have conversations with people. So, as a very conflict-averse society, we avoid them,” Markman explains.

Birds of a Feather Talk Together

Some years ago, Markman did a study using Legos to simulate how conversation can synchronize the way we think about the world. Two people were given a Lego model to build together. One person could touch the pieces but could not look at the instructions, and the other could look at the instructions but could not touch the pieces.

“As a result of doing that, they would have to negotiate a language for talking about these pieces with their partner because we don’t have a vocabulary for all of those pieces,” Markman says.

He pointed out that while labels for each piece were similar between partners, they varied across couples who each came up with their own vocabulary.

In Praise of Forgetting Historical Memory and Its Ironies

Yale University Press, May 2016

by David Rieff

“So two people working together see the world more similarly because they conversed,” Markman says. “And if one of those people talked to someone else, they would see the world more similarly to them; and of course, if we all talked as a group, we would all see the world really similarly.

“But one of the things that comes out of this is, if I talk to you but never talk to this third person, and that third person talks to somebody else, they come to see the world similarly, we come to see the world similarly, but the two groups see the world differently.”

This mirrors what’s happening in the political sphere, Markman says. Our language and ideas are synchronized with those we agree with — it’s the old “birds of a feather” metaphor playing out in real time — while we have become more and more desynchronized with other groups.

“And the more different we get, the harder it becomes to engage in conversation because at some point, if you now get with those people and try and talk to them, you don’t even understand what they’re talking about because they see the world in a very different way,” he says.

Listen to Reason

One way to uproot ourselves from these ideological silos, Keating suggests, is to put less focus on what we have to say and start listening. We already know the way we view the world and what we think is right or wrong. But we don’t know what the other person thinks, and we aren’t going to know unless we listen.

“If people had a model of communication that considered the hearer more important, then perhaps arguments would be more thought of as negotiations rather than a polarization of views,” she says. “We should always consciously think about the person we’re talking to and what they are understanding about what we’re saying.”

It isn’t a new idea, and it’s something we do when conversations or negotiations aren’t so difficult. Keating reminds us that we’re always tailoring what we say to whomever we are talking. Think about the last email you wrote or text message you sent or stranger you conversed with at the grocery store. Our language is constantly transforming depending on the listener, and it should be no different when approaching more high-stakes conversations or arguments.

“Conversations require mutual understanding,” Markman adds. “In order to converse, you have to understand what I’m saying and then contribute something that attaches to what we are talking about. Each of us builds on what the previous person is doing.

“We have to both represent the world in exactly the same way — even if we think we’re disagreeing. You have to understand what I’m saying, and I have to understand what you’re saying in order for that conversation to coordinate and move forward.”

It can be difficult, especially when “we seem to have very polarized views about the way forward to address some pressing problems,” Keating says. “And more than ever there seems to be a fear that if the wrong path is chosen, then there’s going to be some really devastating results.”

Disagreement is OK. “We’re not trying to build a nation of consensus,” Markman says. But a lack of understanding shows room for improvement. No progress can be made without finding common ground. And finding that requires listening to those with whom you disagree, learning their perspective and the experiences that contribute to it and negotiating a mutual understanding of the way the world is.

“There were several people after the last election who said, ‘I simply cannot understand how someone would vote for X,’” Markman says. “Well, if that statement is to be taken literally, it’s a shame. If you truly cannot understand why someone would vote for someone else, then we’re not doing a good job of trying to at least understand someone else’s viewpoint.”