Shark Week brings all sorts of shocking—and horrifying — spectacles to viewers. This year, audiences were promised the first-ever man versus shark swim off, where 23-time gold medalist Michael Phelps will face off against “one of the fastest and most efficient predators on the planet,” a great white.

But, perhaps, what’s more shocking is the steep decline in shark populations over the last half century and the potential and significant impacts it could have on marine ecosystems.

According to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), nearly one third of the 881 species of chondrichthyans — sharks, rays and chimaeras — range from threatened to critically endangered; and 62 percent of the 176 shark species monitored by the IUCN are threatened or endangered by fishing and finning, the latter of which surely escalated when China lifted shark fin soup from the list of extravagances that had been forbidden in 1987.

But according to University of Texas at Austin Distinguished Teacher and American studies professor Janet Davis, humans and sharks have a long and intense history; and with it, the roles of the hunter and the hunted have certainly evolved.

“In thinking about sharks, I got to thinking about longer histories of human-shark entanglements, and how we can think about our changing relationship to the ocean through these entanglements over the centuries,” Davis says.

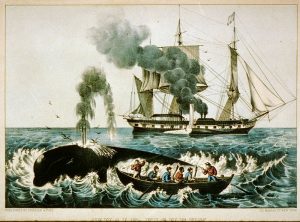

The Hunters

Back in the age of sail, when whaling was a booming industry, captains and their fisherman would encounter sharks frequently in their iconic predatorily and greedy form, Davis explains. Shipmen would lash whale carcasses to the sides of their boats before beginning the marathon process of rendering the body and bringing it back to shore. The meaty cargo would attract thousands of sharks, leaving fishermen to fight them off, often to the sharks’ demise.

But as the whaling industry died out in the late 19th century, and whaling towns like Nantucket became tourist attractions and leisure hot spots, human interactions with sharks, too, began to change. As people flocked to beaches for swimming, fishing, sailing and surfing, they encountered sharks in new, personal and sometimes threatening ways.

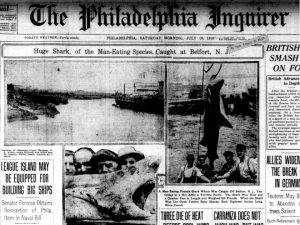

A series of shark attacks off the New Jersey shore in 1916 became the epicenter of a virtual national emergency, leaving President Wilson — who was running for reelection at the time — to face the pandemonium of sharks attacking, U-boats lurking and a polio epidemic all at once.

“The fear and the idea of a shark coming back and feeding, a killer hell-bent on returning — though it was never determined that one shark was responsible for all five attacks — really took hold of the American imagination,” Davis says.

That fear swelled in the waning days of World War II when the U.S.S. Indianapolis, bringing parts of the atomic bomb across the sea from the island of Tinian, was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine, leaving hundreds of sailors as bait for a swarm of deep sea predators. Of the 880 sailors who survived the sinking, only 321 emerged from the water alive after four days adrift in the ocean.

“The Navy actually spent a great deal of resources trying to develop a shark repellent that aviators and shipmen could use if they were stranded to thwart attack,” Davis says.

The Hunted

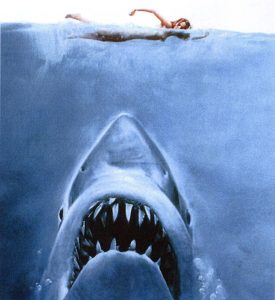

Fast forward to June 20, 1975 — just weeks after the U.S. led the final evacuation out of South Vietnam leaving the North to reunify the country. “There’s all sorts of deep shocks happening in America. Watergate is still on people’s minds. And all of these shocks, I would argue, come together in the body of a big mechanical shark named Bruce,” Davis declares, referring to the blockbuster release of JAWS.

Peter Benchley’s idea for his novel, released just one year earlier, stemmed from a story he heard in the 1960s about a fisherman from Monauk, New York, who legend says reeled in a 4- to 5,000-pound great white. Benchley thought, what if a shark of that size decided to visit a beach community and then “afflicts it?”

“Movie rights were signed before the novel was even finished,” Davis says. Its enormous popularity seemed to feed off not only Americans’ fears and anxieties about sharks, but also the stiff tensions surrounding the recent war and percolating mistrust of the federal government.

“It’s a sensation as a novel, but becomes even something bigger as a movie, unleashing a frenzy of shark interest: tournament fishing for sharks, shark fear, but also shark love,” Davis says,

noting that some conservationists argue JAWSmania led to a noticeable decline in shark population off the North Atlantic, due to sport fishing.

Davis recalls a story from her research in which Benchley began to reconsider the implications of his work and became a dedicated environmentalist. She describes one point in the 1980s when Benchley was scuba diving off the coast of Costa Rica and happened upon hundreds of finned shark bodies lying on the ocean floor — a moment that redefines an order of animals.

“All of these forces collide to create an order of animals that we think of as being terribly dangerous to us, but then the question turns back on itself: What kind of dangers do we pose to them?” Davis asks.

It’s in this context that Shark Week was born on Discovery Channel in 1988.

Recasting

“In its advent, Shark Week really focused on this sort of conservation ethos, recasting sharks away from lurking predators — because really only four species are truly dangerous to people: tiger, bull, oceanic white tips and great whites,” Davis says. “Over time though, what happens with Shark Week is that it gradually turns into something else: less focus on the environment, less focus on preservation and conservation, and more emphasis on spectacle.”

Like much of television, spectacular presentations of reality fill the screen, and viewers are met with awe-inspiring interpretations of shark natural histories such as “the Megaladon, the 50-foot ancient predator of old that was such a killing machine,” Davis jokes. “What if they’re still out there?”

Publicity for the annual event is saturated with “humorous and campy” advertisements that have “come to define our relationship with these animals in pop culture terms,” Davis explains.

But are sharks losing out for the sake of entertainment?

Human and sharks have become deeply tied throughout the centuries, physically, pop-culturally, socioeconomically and even politically; from whaling to war and bookshelves to the big and silver screens, sharks are very much a part of human life.

“As strange and as distant and as other they may seem, they are very much at the center of who we are,” Davis sympathizes. “And, while conservation measures within our country have done a pretty good job at stabilizing population on our coast, sharks don’t know national boundaries, and they face grave danger in other places.”