…And all the while, I kept thinking about that great old Whitman poem… ‘When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer.’

I…I don’t know it.

Anyway…

Well, can you recite it?

Pathetically enough, I could.

With some encouragement from Walt, Gale continues:

When I heard the learn’d astronomer,

When the proofs, the figures, were ranged in columns before me,

When I was shown the charts and diagrams, to add, divide, and

measure them,

When I sitting heard the astronomer where he lectured with much

applause in the lecture-room,

How soon unaccountable I became tired and sick,

Till rising and gliding out I wander’d off by myself,

In the mystical moist night-air, and from time to time,

Look’d up in perfect silence at the stars.

After watching this clip from Breaking Bad, a group of first-year students from the Dell Medical School read the poem silently, using a close reading protocol that guides them to paraphrase, observe and analyze. English professor and associate director of the Humanities Institute Phillip Barrish facilitates the discussion. One student points out that there is a tension in the poem between real-world experience and scientifically mediated experience. Another student mentions how in the first part of the poem the language is analytical and passive and in the second, where the speaker takes action, the language becomes more sensory and subjective. Finally, the students note that this literary shift, a break in the poem, happens with one word: sick.

Illness is disruptive. It tears apart the fabric of a person’s life as well as the lives of family members and even their community. Imagine an earthquake, shockwaves radiating from an epicenter along fairly predictable, or at least observable, paths. Imagine the aftershocks and the features of the landscape hinting at more earthquakes to come. Imagine the built environment at ever-increasing risk. What would happen if geologists only looked at the moment of the earthquake itself, treating it as a discrete event separated from human activity? They would put whole communities at risk. Yet, that’s how we often understand and expect medicine to operate — in tight focus, at a microscopic, individual level, and solely in a moment of crisis.

But this wasn’t always the case. As Dr. Steve Steffensen, chief of the Learning Health System at Dell Medical School explains, until about 150 years ago Hygeia, or wellness, took precedence over — or was at least equal to — Panacea, universal cure. There was really very little that could be done once someone became sick. However, various innovations, including control over bacteria and better means of diagnosing illness, led to medicine focusing on, as he says, “the hope of cure” rather than prevention. But the pendulum is now swinging back.

“And if your focus is on health, then you need to ask the question: Where does health happen? Does it happen in my 10-by-10 exam room when you come to see me with a condition to treat? … I can prescribe something for you. I can do a diagnostic work up. I can help you manage a condition. But rarely does health happen,” says Steffensen, who believes it does happen when we escape the confines of the lecture hall, the examination room and even technology. “Health happens outside of our hospitals and institutions where we work, live, pray, play. Medical school will teach you what a human is; the humanities teaches you what it means to be human.”

“Medical school will teach you what a human is; the humanities teaches you what it means to be human.”

Dr. Steve Steffensen

Medical professionals are now understanding that the observation and reflection skills that the humanities disciplines engender need to be reintegrated into their practice to better serve patients, the community and clinicians themselves. Consequently, many medical schools are now setting up medical humanities institutes, or, at least, developing and implementing medical humanities curricula. At Dell Med, arts and humanities are foundational to the mission of patient-centered care and their commitment to the community. According to Steffensen, “everyone from our dean to our vice deans to our faculty and staff understands and appreciates the importance of the humanities.” Thus, as the Dell Medical School continues to grow, humanities will be integrated into student-focused curriculum and development, faculty development, community engagement and collaboration with the humanities expertise on the Forty Acres.

HUMAN TOUCH

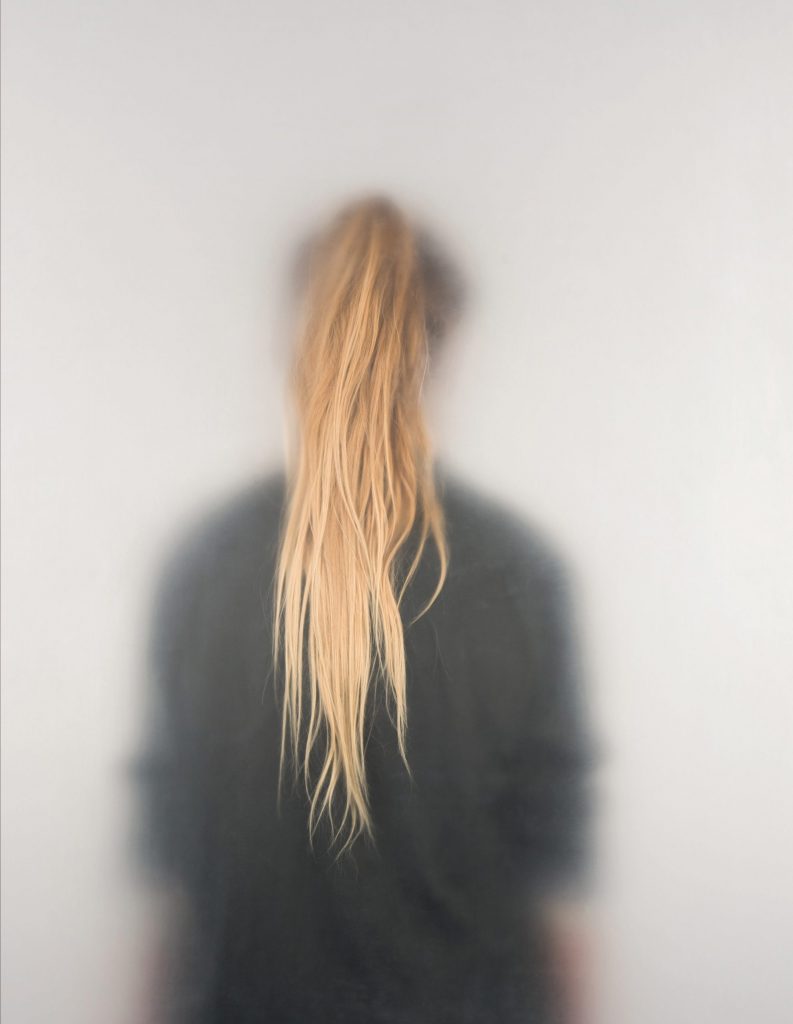

Ann Hamilton’s public art project O N E E V E R Y O N E, commissioned by Landmarks for the Dell Medical School, is a series of community portraits in which the experience of touching is made visible, an apt metaphor for Dell Med’s commitment to patient-centered care and the natural intersection of medicine with the arts and humanities. These images are also indicative of the deep collaborations and lasting cross-campus relationships built to welcome Dell Med to the UT community. As Pauline Strong, professor of anthropology and director of the Humanities Institute, explains, “the health humanities is an area in which exciting research and community partnerships are occurring nationally and internationally.” Consequently, the Humanities Institute chose as its theme for 2016-2018, “Health, Well-Being and Healing,” to bring together UT faculty members, students, clinicians and community researchers to, in Strong’s words, “collaborate on programs that seek to understand health, illness, healing and health justice in the broadest possible perspective, across time, space and academic disciplines.” This focus has also led to additional collaborations with Dell Med, Landmarks, the Blanton Museum of Art and the UT English department’s Texas Institute for Literary and Textual Studies (TILTS).

TILTS chooses a different theme for each academic year and in 2016-2017 focused on “Health, Medicine, and the Humanities.” A series of speakers covered a broad range of topics in medical humanities including gaming and its applications to the humanities and health care education, race and metabolic disorders, disability studies, and death as a cultural and medical phenomenon. Additionally, they collaborated with the Humanities Institute in bringing other distinguished lecturers to campus including poet and physician Rafael Campo and Priscilla Wald, professor of English and women’s studies at Duke University, who spoke on “Cells, Genes, and Stories: HeLa’s Journey from Labs to Literature.”

The TILTS–Humanities Institute collaboration also sponsored a week-long residence by Dr. Rita Charon, professor of medicine and founder and executive director of the Program in Narrative Medicine at Columbia Presbyterian Medical School. In addition to delivering a public lecture “The Shock of Attention: Bodies, Stories, Healing,” her residence as the C.L. and Henriette Cline Centennial Visiting Professor in the Humanities included a panel discussion with university and community leaders on the notion of a caring society, and a lecture at Dell Medical School, where she met with students and inspired several of them to form their own close reading and expressive writing group based on the Columbia Presbyterian model.

TELLING THE PATIENT’S STORY

Dell Medical School student Virginia Waldrop, now in her second year, was excited when she saw the poster advertising Charon’s lecture at Dell Med because she knew a bit about Charon and Columbia Presbyterian’s narrative medicine program. A former humanities major who enjoys creative writing and reading literature, she knew that several of her fellow students would also enjoy a chance to get together outside of their regular studies to read literature and reflect on their experiences as an outlet to help them document their experience, preserve their humanity and “observe some of the aspects of ourselves that otherwise might be squashed over the course of four years of intense study.”

Waldrop and her fellow students approached the Humanities Institute and proposed a reading and writing workshop, a concept that Strong embraced. She turned to Barrish to develop an informal class that would be informed by Charon’s teachings about narrative medicine and the Close Reading Interpretive Tool (CRIT) protocol developed in the Department of English by several graduate students and faculty members, including Barrish.

Most importantly, the students saw Charon’s work at Columbia Presbyterian as a model that could help them become more adept at patient-centered care. In his introduction to Charon’s lecture at Dell Med, Steffensen emphasized that the most important job of a physician is to tell the patient’s story, citing the physician’s narrative summary as a form of contract for a “sacred relationship” that doesn’t exist in other venues and might be the only place where a patient’s story is told. Thus, evaluation of narrative prose — “the ability to have the expertise to write [the patient’s] story, to critique that story, to reflect on what that patient has told you” — is a skill that physicians need to know in order to create a plan that is beneficial to the patient.

Physicians need to be trained to recognize metaphors, images, allusions to other stories, genre, mood — in other words, the things that literary critics look for in literary works.

In her book Narrative Medicine: Honoring the Stories of Illness, Charon explains that the better equipped physicians are to listen for or read for a narrative, “the more accurately they will entertain likely diagnoses and be alert for unlikely but possible ones.” In order to do this, physicians need to be trained to recognize metaphors, images, allusions to other stories, genre, mood — in other words, the things that literary critics look for in literary works. Literature, “because of its verbal richness and complexity,” as Barrish puts it, is not only good for teaching these competencies, but it can also help the students who come from a strong science background to recognize and “perhaps come to tolerate” ambiguity, conflicting evidence and the possible need to revise one’s initial assumptions about a situation.

Reflective writing also helps build these literary skills — all of which serve to strengthen the core competency of observation — and it can also build empathy. As Charon argues, the ability to shift perspective to acknowledge another point of view is critical, and it may be weak in the contemporary health care profession. However, it’s a skill that can be taught, and one way is through a tool developed at Columbia Presbyterian called parallel charts.

Parallel charts give health care students a place to express things they can’t write on an official medical chart. Their value to students is more instructive than therapeutic, helping them better understand a patient’s experience and reflect on their own journey through medicine. When health professionals write about their experiences, they discover aspects that were not otherwise evident to them. Charon notes that students who write parallel charts report having more confidence in treating seriously ill or dying patients and in delivering bad news.

FORCE FOR GOOD

The informal class incorporated both aspects of Charon’s program: close reading and expressive writing. The students met with Barrish for two hours once a month, and no outside work was required of the already taxed students. Waldrop says this allowed everyone to start on the same foot, and all ideas and perspectives were welcome. Over the course of the spring, the group analyzed poems and brief prose selections from physician-writers including William Carlos Williams and Rafael Campo, and short pieces and poems from other literary figures including Junot Díaz and Walt Whitman.

Additionally, the method of close reading helped students become more attuned to their patients as complex human beings and, according to Barrish, develop the ability to recognize meaningful details and “weave them into a complex interpretation that tries to do justice to a text, whether it is a literary text, an intake interview with a patient or a discussion with a patient’s family.” The protocol for the close readings, which was adapted from Charon’s work and the CRIT tool, also served to equalize the group; not all of the students were from a humanities background, and so this scaffolded yet flexible method made them feel supported in potentially unfamiliar territory.

In the second half of each session, students drew upon their individual experiences, emotions and interests in responding to open-ended prompts loosely related to the day’s reading. Students then took turns reading what they had written to the group, and each writer received feedback from the class and instructor about what was especially striking or effective in the piece. The writing exercises emphasized reflection and expressive communication as well as engaged listening and discussion.

In summarizing the evaluations from the workshop, Strong says the experience helped enhance the students’ skills in literary analysis, added to their sense of community, prompted self-reflection and discussions relevant to their professional formation, and improved their ability to offer patient-centered care. Aydin Zahedivash, now a second-year student at Dell Med, said that the workshop was “a really cool way to reflect on how the profession of medicine affects our patients.” The students generally also indicated the workshop made them more observant, more able to process difficult experiences with patients, and more able to maintain empathy and compassion in the clinical environment. All strongly agreed that they would recommend the workshop to other Dell Med students.

One of the most powerful sessions, according to Barrish, was a discussion of William Carlos William’s “The Use of Force” — a story that describes an incident in which Williams has to restrain a child in order to perform an examination. The students were then asked to describe a personal experience inside or outside of a medical context in which power was exerted either by the student, against the student, or in a situation they witnessed and in which they were somehow complicit. One student wrote about trying to buckle her 2-year-old into a car seat, and the ambiguity of using force to ostensibly do something for someone’s good. As Barrish explains, this discussion connected directly to the medical school curriculum through the concept of patient compliance, and how difficult it is to understand and navigate humanely the myriad reasons why a patient may not always comply with a physician’s instruction. Zahedivash said he felt this session was “particularly impactful,” and that it “served as a reminder of the importance of professionalism.” Barrish concludes, “I wouldn’t say that session was the most successful, but I would say that it was the most emblematic of what we were trying to do.”

Students are required to take medical ethics class as part of their accreditation, but as Charon points out, the field of medical ethics seems to be grounded in the assumption that the doctor-patient relationship is adversarial and needs to be mediated by law and moral principles. Practitioners are now realizing that a knowledge of medical law is no longer enough to fulfill ethical duties to patients, but bringing literature or art into ethics instruction can help medical students experience these issues viscerally and be better equipped to make decisions based on their own values. As Barrish explains, ethics asks “What would you do in this situation?” while literature asks “What is the whole experience — physical, emotional, social, spiritual, etc. — of the situation and the people involved?” Armed with an understanding built on empathy, a physician is potentially poised to make a more humane decision and better fulfill what Steffensen refers to as the “sacred obligation to care.”

In turn, this potential change in ethics could lead to a different understanding of public health. Physicians can learn from humanities fields beyond literature — anthropology, art history, classics, history, and so on — to extrapolate from individual cases the influence on communities and the patterns that have led to social inequalities that in turn lead to health disparities.

The Humanities Institute is interested in exploring these connections in many contexts. Not only will this year’s faculty fellows be presenting their work in a symposium in the spring, there will be additional lectures and events centered on medical humanities. Next summer, the Institute will also offer a Pop-Up Institute, “Health and Humanities: Narrative Medicine, Equity and Diversity, and Community Practice,” supported by the Office of the Vice President for Research.

As for the Dell Med students, they hope that the informal class will continue. And they aren’t the only students wanting to continue the work started this year. Thomas Nguyen (’17) was a neuroscience major who started writing poetry after taking an undergraduate studies course with English professor Brian Bremen, co-organizer with Barrish of the TILTS 2016-2017 program. Nguyen was also the event organizer for TILTS. Poetry intrigued Nguyen as a way of describing creatively what he was learning about the body because both medicine and poetry are “concerned with human contact and stories.” He had planned to go directly to medical school, but after Charon’s visit he applied and was accepted to the narrative medicine program at Columbia Presbyterian. Now he hopes to do in New York what he did here in Austin when he taught writing workshops at Austin State Hospital: “Narrative training will help me honor each story I hear — its pauses and silences, its tone and temporality, its form and frame, the body language and eye contact I witness — and then be moved in such a way to care for the patient. That’s as simple and as difficult as it sounds.”

“Asylum” (excerpt)

A patient from unit two

is screaming, threatening

to choke herself, but you can’t hear

anything, just see veins pulse

around her neck, branches

bare like elms in wintertime.

Silence still like sunrise

over Lake Vermilion.

You tell her to write down her words,

it helps with the processing.

-THOMAS NGUYEN

ONEEVERYONE is a public art project commissioned by Landmarks in 2017.