In English, writing is very different than painting. But in Hindi, and specifically in the landscape of Mithila folk art, “to paint” is “to write.” The distinction could be a phenomenon of grammar, or it may have to do with the fact that the tools of this trade are more like pens than brushes.

As an apprentice artist during my year as Fulbright scholar in India, I learned to paint in the Mithila style. In a surprising way, this hands-on course of study will help me — more than years of academic preparation could — “to write” my dissertation, a study of economic development in India, for the Department of Asian Studies at The University of Texas at Austin, my home as a Ph.D. student.

With the help and generosity of two of India’s most celebrated contemporary folk artists, Manisha Jha and Santosh Kumar Das, I was taught to use the delicate metal nibs, which characterize authentic Mithila art today, also known as Madhubani painting.

“Madhubani” refers to the political district in Bihar, located in North India, where this art form was first documented by the British in the 1930s. “Mithila” refers to a larger region, expanding over the Himalayas into Nepal; Mithila corresponds to a culture, an ancient kingdom, and the heroine of the Indian Ramayana epic, princess Sita. We are told that such paintings were made for Sita’s wedding and that this art form was used to adorn mud walls, serving as a type of ritual manual for religious rites of passage for centuries.

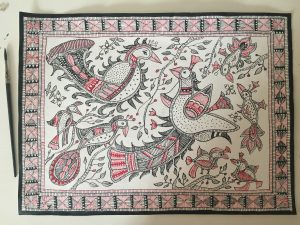

Mithila art is recognizable by the bold lines giving shape to religious and natural motifs. Since its rise in popularity in the 1980s, traditional iconography (such as Hindu gods and goddesses) filled the tourist marketplace. Today, it can be found as a design on clothing, housewares, notebooks and on canvas in some higher-end galleries.

As a visual language, it has evolved to represent autobiographies, and some often political commentary on issues like domestic violence and women’s health and religious violence. When these are expressed on paper, “painting,” takes on an ever-greater sense of “writing,” as people share their stories. Paper is where my story as an artist began.

It took a few months before I could dip the nibs, which look and feel like calligraphy pens, with confidence. One must mix acrylic pigments with water until it has the viscosity of something not quite ink, but not quite paint. The proportions shift subtly based on seasons and environments, and the quality of these poster paints is inconsistent, in spite of being industrially produced.

Working six days a week alongside professionals was grueling work. Artists often work on the floor. Challenges of the first six weeks included bruises, calluses and strain on the eyes. Eventually, I found the rhythm together with women whose hands moved with the swift confidence of professional musicians whose instruments become extensions of their bodies. I rarely found a workshop not filled with song and humming, colors and lines flowing.

My paintings are a record of my progress. Every painted corner comes with a story – not about me, but the communities of artists who taught me: New babies, weddings, family members getting jobs, losing jobs, moving, opportunities, holidays, fasting days. I became a part of the larger community of “Madhubani painters.”

Seven years of Hindi, trips to India and academic work unlocked many doors but left me looking at this industry from the outside. Taking up an apprenticeship did something unexpected: I acquired more than the skills of a painter, but I adapted a type of physical literacy with the work. Often researchers collect data, my data is written on my body.