Rikke Cortsen is occasionally surprised to remember that not everyone she meets is an avid reader of comic books. She’s been reading comics of one sort or another since her childhood in Denmark, as evidenced by the hundreds of colorful volumes lining her office bookshelves.

“Working in comics you always run into the discussion of high culture and low culture and everybody says that it’s not really a thing,” she says. “But then you tell people you have a Ph.D. in comics and they giggle and you realize it’s still a thing.”

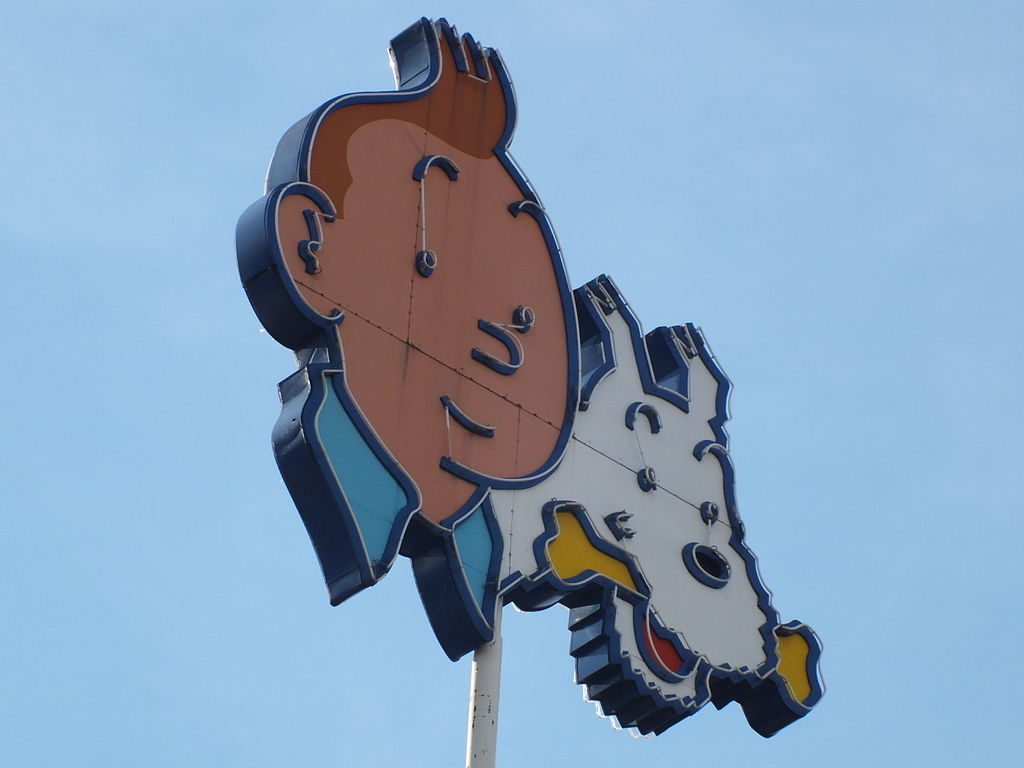

Cortsen, a visiting lecturer at UT Austin’s Department of Germanic Studies, sees comics unquestionably as art and also as a valuable teaching tool. While only one of her UT course offerings, Northern European Comics,focuses on the form specifically, she employs comics in all her classes as a means of teaching both language and culture.

The medium is especially useful in language classes, where students who had previous bad experiences in the subject often view their language requirement with a bit of dread. Humorous comics can enliven the learning of basic language skills, Cortsen explains, citing a translated Calvin and Hobbes strip she shows her Danish class that conveniently features multiple conjugations of the action of eating worms. And breaking up text into smaller pieces goes a long way toward reducing the anxiety of reading in a foreign language. Students might encounter just as many unfamiliar words in a series of comic panels as they would in a book excerpt, but because the former appears easier they’re more likely to persevere.

Cortsen stresses that comics are also great for teaching visual literacy, something educators often forget in crafting the requirements of a well-rounded degree plan. While most people acknowledge the complexity of literature and the skills needed to interpret it, there’s a tendency to assume that we know how to read images intuitively. But images too can have multiple meanings. When Cortsen’s students look closely at comics and discuss what they see, different interpretations quickly emerge.

“That leads us on to this discussion of what are some of the many layers and could it be that the artist also drew this panel so that what you saw and what you saw are both in there at the same time,” she says.

While the field of comics scholarship has grown considerably since Cortsen attended her first conference, misconceptions about the medium’s artistic merits persist. One such assumption is that the images in comics exist merely to illustrate text, an outsourcing of the work that would otherwise be done by a reader’s imagination. But there are many ways text and image can interact. A story might be divided between the two, with text and image each providing different information. Images can even oppose rather than support text, undermining the words of an unreliable narrator, for example.

But the quality that perhaps most fascinates Cortsen is comics’ ability to visualize time in a way that moving image media like film and television can’t.

“Interesting things can happen with time and space in comics because of the way the medium is set up,” Cortsen explains. “You can have things that are technically the past, and the present, and the future right next to each other on a page. And the reader can put them together and navigate that.”

So, while comics are occasionally called by the more scholarly-sounding moniker “sequential art,” the way they are read is often far from a straight line.

Ever aware that many students’ only concept of the medium are superheroes, Cortsen aims to include as many styles and genres of comics in her classes as possible. I admit to her that I had written off comics due to that very ignorance before discovering various indie comic artists in college. Had I grown up in Denmark, I might have been less of a snob about it. The Danes are prolific readers of comics, and superhero narratives are not big there. When they do crop up, it’s usually in the form of satire.

While still more cape-strewn than that of Northern Europe, the U.S. comic landscape is changing, as well. Cortsen says she’s excited to see more diverse protagonists not just in indie comics, but also in the mainstream. Even the Marvel and DC dominated superhero industry is starting to realize that marketing to only one demographic may not be a winning strategy. (Recall the enormous success of the Black Panther movie if you have any doubts.)

However, amidst the ever-growing catalog of comics there are bound to be some duds. No one would say, “I don’t like books” just because they’d read one bad novel, yet one bad comic book experience can lead readers to assume they hate the medium as a whole.

“As with so many other artforms, there are good comics and there are not so good comics,” Cortsen says. “No matter who you are and what your interests are, I bet you I can find you a comic that you will find interesting.”

For those who want to experience the comics of Northern European first hand, Cortsen has some recommendations to get you started (all of which are available in English translations):

Munch by Steffen Kverneland (Norwegian)

Artist biography of the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch.

Book of Hope by Tommi Musturi (Finnish)

An old couple prepares for the last sections of life and the man remembers the past.

Fruit of knowledge by Liv Strömquist (Swedish)

The cultural history of the vulva told in an up-beat humorous fashion.

Today is the last day in the rest of your life by Ulli Lust(German)

Autobiographical account of a young woman’s travels around Southern Europe in the 1980s.

Zenobia by Morten Dürr and Lars Horneman (Danish)

A young Syrian girl tries to cross the Mediterranean to escape the conflict in Syria.