Historical research can be exhausting work. Hours spent sifting through archives in search of elusive details from the past may yield nothing, but it may lead to an extraordinary discovery.

“It can be mind-numbing,” says Steven Hoelscher. “And, of course, you don’t always find what you’re looking for and sometimes you don’t even know what you’re looking for.”

Hoelscher, a professor of American studies at UT Austin, wasn’t looking for lost works by Langston Hughes when he came across an unfamiliar essay by the author, but his curiosity was piqued by the manuscript. What was it? Where did it come from?

It would take over a year to piece together the essay’s origin. There weren’t a lot of clues, but it appeared to Hoelscher to be a foreword to a largely forgotten novel by journalist John L. Spivak, whose archive is partially housed at the Harry Ransom Center where Hoelscher discovered the manuscript.

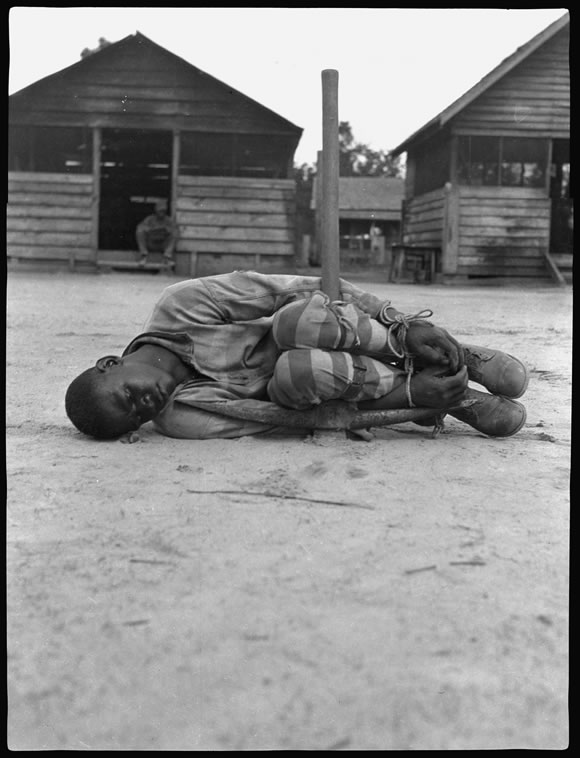

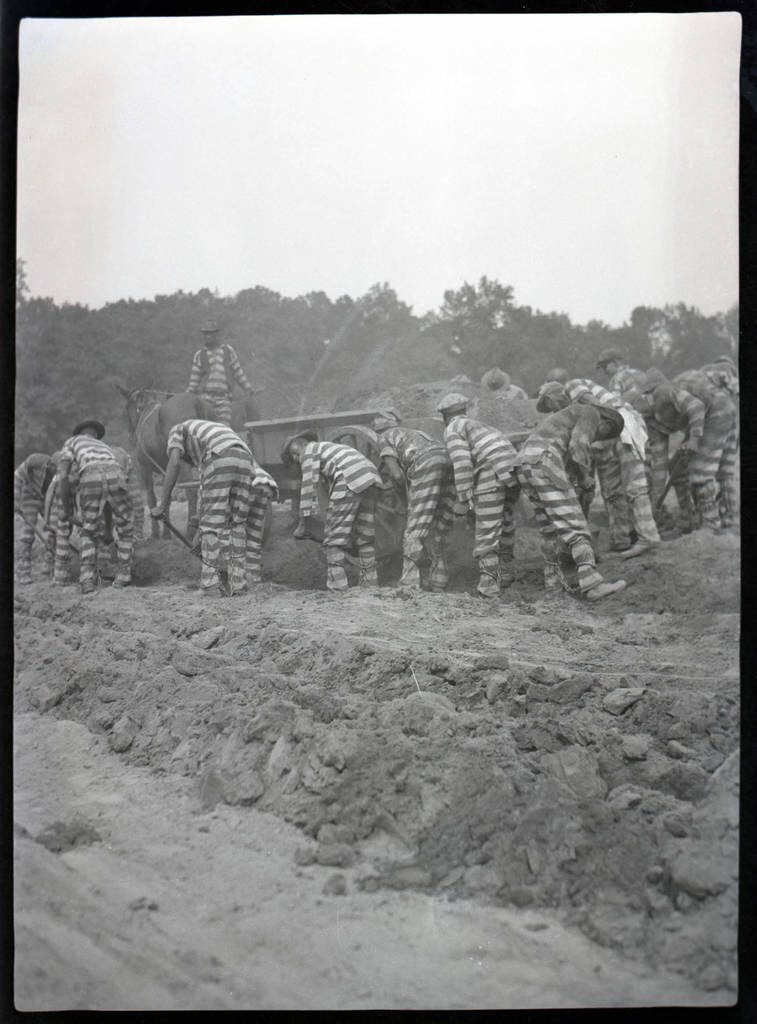

Spivak’s 1932 novel, Georgia Nigger, while nominally a work of fiction, was grounded in two years spent investigating the treatment of African American prisoners forced to work on chain gangs in the Jim Crow South. The book included an appendix of photographs documenting the brutality of the incarceration system. It was studying these images that led Hoelscher, who also serves as faculty curator of photography at the Ransom Center, to Hughes’ essay.

“As a researcher of photography, I always rely very heavily on manuscript materials to shed light on the creative process,” he explains. “Viewing photographs in isolation of their surrounding context makes no sense to me. So, looking for whatever manuscripts might go along with the photographs — correspondence, business records, notes, tear sheets, reviews — is always the first thing I do.”

In his essay, Hughes relays a personal anecdote in which he and an unnamed friend encounter an escaped prisoner from a chain gang while driving through segregation-era Georgia. The young man describes the atrocious conditions of the forced labor system and reveals that he ran away to reunite with his wife in Atlanta. Hughes and his friend try to convince the man to flee with them to the safety of the North and from there send for his wife. Ultimately, for reasons Hughes can only speculate on, the man opts to take his chances in Georgia.

To trace the origin of the story, Hoelscher reached out to Hughes’ biographer Arnold Rampersad, who was able to confirm his theory about the timing of the event. The unnamed friend, it turns out, was most likely fellow author Zora Neale Hurston and the incident Hughes described would have occurred during a road trip the two took through the U.S. South in 1927. A visit to the Hughes archive at Yale University further corroborated the date, but the essay itself remained a mystery. Rampersad agreed that it appeared to be a foreword to Spivak’s book, but was unaware of Hughes having written such a thing. And no editions of the book with Hughes foreword seemed to exist.

It was only by digging deeper into Spivak’s documents at the Ransom Center that Hoelscher finally found the answer. The essay was written not for an American edition of Spivak’s novel, but for a Russian translation published in the Soviet Union in 1933. This was revealed midway through a long series of letters between Spivak and Walt Carmon, an American editor living in Moscow at that time, in which the two discussed the possibility of bringing the book to a Russian audience and of asking Hughes to write its foreword. Hoelscher eventually tracked down the Russian edition at Notre Dame University’s Special Collections Library and made copies of the translated Hughes foreword so that a colleague in Slavic studies, Marina Alexandrova, could compare it to the original document.

For a short period in the late 1920s and early 1930s, Soviet Russia offered African American artists and intellectuals a reprieve from the racism of the U.S., and Hughes lived there from 1932 to 1933. In venturing to Russia, Hughes traded the disadvantaged status of a black man in the U.S for one of privilege.

The University of Texas at Austin)

“He’s treated like a celebrity,” says Hoelscher. “He traveled extensively. It was a really inspirational and artistically productive time for him.”

But Hughes’ foreword to Spivak’s book is a reminder of the realities of life back home, where convict labor camps created a new kind of slavery and educated Northern blacks travelled through the South at their peril. The risk Hughes and Hurston undertook in attempting to help the escaped prisoner easily could have led to the loss of their own freedom.

At the time of its release, Georgia Nigger sparked its intended outrage at the inhumanity of chain gang labor and torture among black and liberal white audiences, but the book and its subject matter are unfamiliar to many contemporary readers. Hoelscher and other researchers see the chain gangs of the Jim Crow-era South as essential to understanding our county’s current mass incarceration crisis. Projects such as The Equal Justice Initiative’s Legacy Museum: from Enslavement to Mass Incarceration, which opened in Montgomery, Alabama in 2018, are working to expand that knowledge.

“There is an emerging sense of the necessity to understand that period as critical to American race relations,” says Hoelscher. “Most Americans don’t know the history of convict leasing or chain gangs in the South, and why that system is so central to our own moment. My hope is to make a small contribution to that historical project.”

The Langston Hughes essay with an introduction by Steven Hoelscher is published in the July/August issue of Smithsonian Magazine.