Edward Carey’s office is filled with fanciful artwork, including several large drawings of the gloomy-eyed characters who inhabit his books. But the item that immediately catches my eye is a bowl of small, cylindrical objects that at first glance appears to be an ashtray overflowing with cigarette butts. These, it turns out, are pencils, worn down to the nub, which the author used to illustrate his most recent novel, Little. A fictionalized account of the life of the woman who would become wax museum pioneer Madame Tussaud, Little, like much of Carey’s writing, is interwoven with his drawings.

“For me, the act of doing drawings is a way of fully immersing myself in the world,” says Carey, an associate professor of English at UT Austin. “And sometimes the drawings contradict the writing and then I play around with it, but they have to come into existence together.”

There’s a lot of back and forth between Carey’s drawing and his storytelling. Drawings often take unexpected turns, pulling the narrative into new directions and vice versa. Hearing him talk, it seems the process might go on indefinitely if not for words and images being captured in printed books. Art for his forthcoming novel about Pinocchio craftsman Geppetto’s stint in the belly of a giant shark has already exhibited in Tuscany, but the text is still working through its transformations.

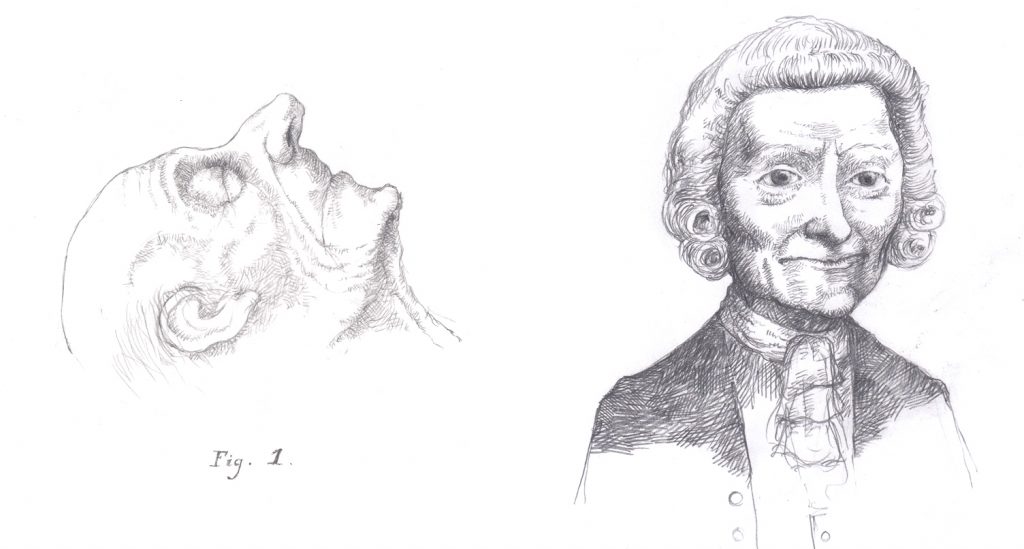

Both the drawings and narration in Little are from the perspective of protagonist Marie Tussaud (born Marie Grosholtz), thus the humble pencil in which the illustrations are rendered. Carey combed through countless drawings from the period to create a more realistic style than what he employed in previous books, as well as crafting some of the objects that appear in the story — a wax mask, a wooden doll Marie carries with her throughout her life — in order to get a better understanding the character’s world.

Finding the narrative voice for a character based on an historical person had its own challenges. For this, Carey drew inspiration from fiction as much as fact, partly because fiction is his trade but also, he notes, “There have been various nonfiction biographies of her but they’re not very exciting, which seems extraordinary given who she was. But the reason they’re not is because Marie Grosholtz,” and here he drops his voice to a whisper for effect, “told a lot of lies.”

Marie, he explains, in addition to being a survivor of the French Revolution who touched history through her wax sculptures, was a smart business woman who knew when to embellish her own history to draw in audiences. So, while the novel is extensively researched, Carey opted to leave in some of his protagonist’s tall tales, allowing her to become the folkloric figure he first encountered while working at Madame Tussaud’s in London upon finishing college.

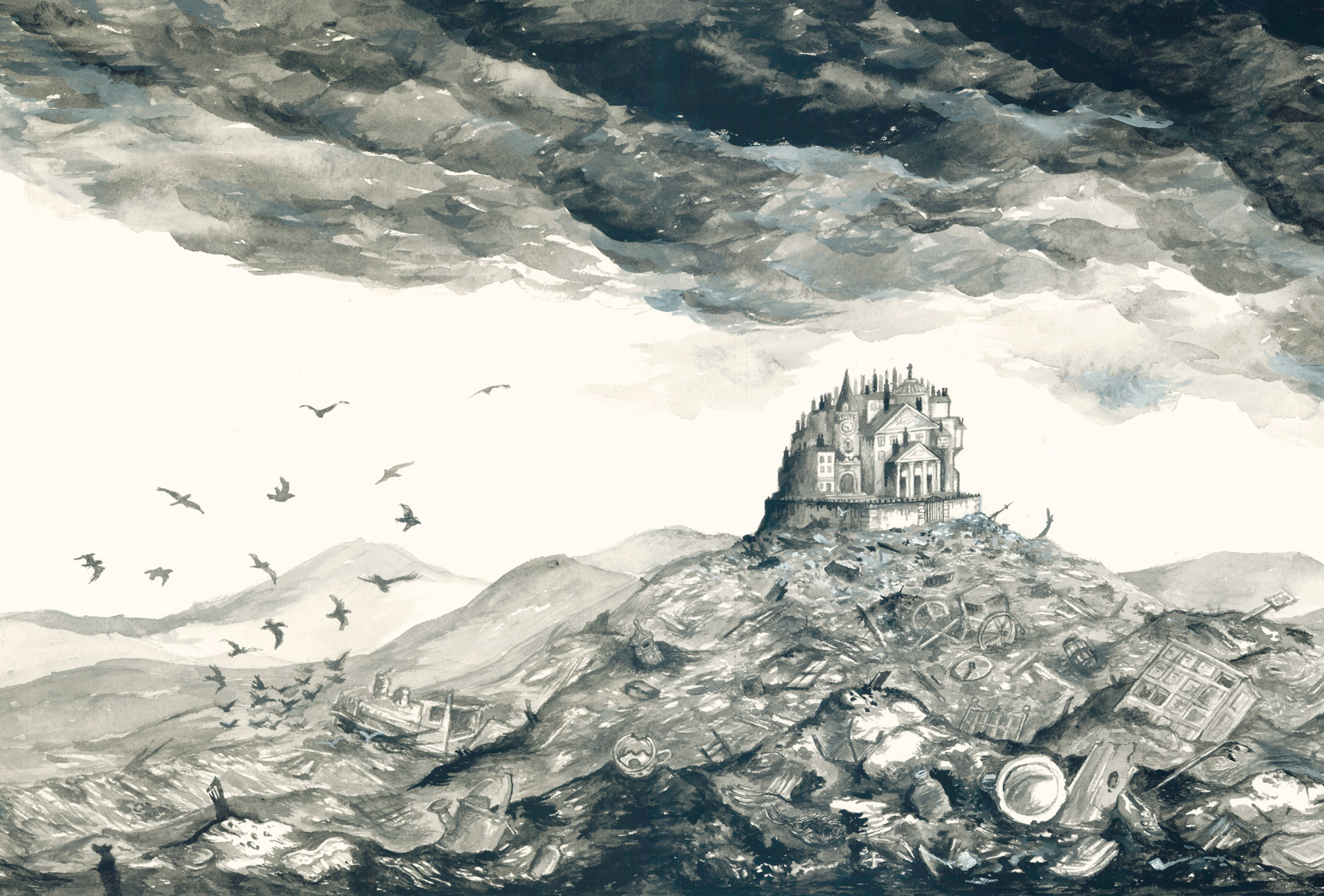

It took 15 on-and-off years for Carey to complete Little, and he might have abandoned the project completely had it not been for a career detour into writing books for young adults. Creating The Iremonger Trilogy, a series set in a stylized old London featuring talking objects and other fantastical elements, proved a turning point for Carey.

Little: A Novel

Riverhead Books, Oct. 2018

By Edward Carey

“It totally reset me as a writer.” he explains. “It made me remember the joy of fiction, and I’d kind of lost it a bit.”

Writing in the spirit of old school adventures like Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island and allowing his imagination to roam into unfamiliar worlds was freeing, even if the speed at which he needed to complete the second and third installment was brisker than his usual pace (no one ages faster than young readers). Ultimately, the experience convinced him to revisit Little from a less conventional angle.

“Writers need to remember to give ourselves permission to go to places we want to go to,” Carey notes. “Not to places we feel we have to go to.”

“For me, the act of doing drawings is a way of fully immersing myself in the world. And sometimes the drawings contradict the writing, and then I play around with it, but they have to come into existence together.”

Edward Carey

While the Iremonger series was written with a younger audience in mind, Carey has reservations about compartmentalizing books solely by age or readership. He was recently awarded a Guggenheim fellowship, which will be used to write a new book set in a children’s hospital, but the story will likely fall somewhere in between literature for children and grown-ups. “I’m going into it with an open mind.” he says.

The new novel was inspired by an actual children’s hospital in Florence, Italy, where Carey was a writer in residence, a wonderful place with a dedicated and brilliant staff. But realism not being his area of expertise, Carey is taking a different approach.

“I want to write almost an antithesis of what that hospital is.” he says. “I’ll make a monstrous hospital.”

He means this rather literally, and is already sketching the beastly embodiments of diseases that will haunt the institution’s halls.

It’s hard to believe that Carey once felt he was losing his sense of the joy of storytelling. His love of literature is unmistakable as he discusses his favorite books, the abundance of excellent new writing coming out every year, and the experience of working on his own projects.

“When you’re writing fiction, you can have the most enormous budget, and as many characters and as many locations as you want,” he says, recalling the constraints of writing plays earlier in his career. “And it’s the most incredible freedom.”