The Presidential elections of 2000 and 2016 were controversial, in part, because it seemed like the wrong person won.

In 2000, Republican George W. Bush defeated Democrat Al Gore by 5 electoral votes after losing the popular vote by about 540,000. And in 2016, Republican Donald Trump garnered 27 more electoral votes than Democrat Hillary Clinton but lost the popular vote by nearly 3 million.

To many, the results seemed like a fluke: What are the odds of this happening, especially twice in the last two decades?

Higher than you probably think, say UT Austin economists Michael Geruso and Dean Spears whose paper on “inversion” elections was recently released by the National Bureau of Economic Research. The paper is part of the University of Texas Electoral College Study and was coauthored by Geruso, Spears, and economics and math undergraduate Ishaana Talesara.

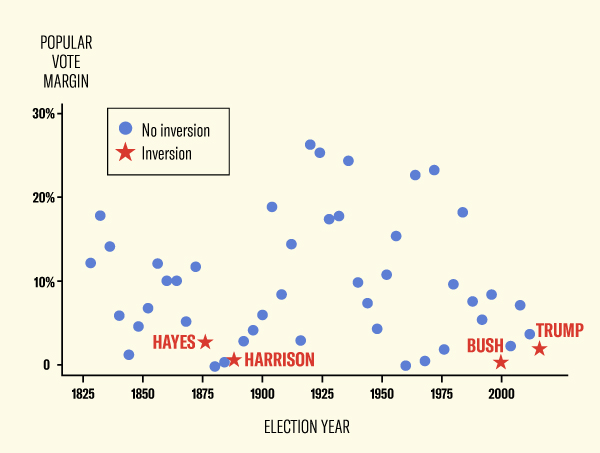

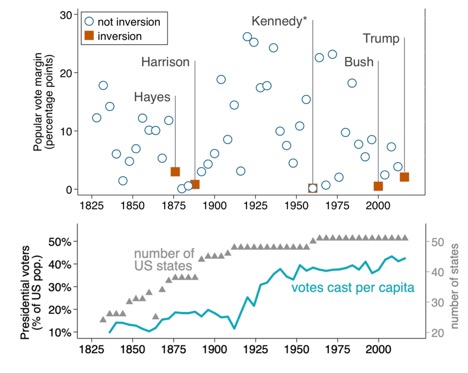

According to their work, inversion elections are very likely in close elections. Although they’ve only happened four times in U.S. history — 1876, 1888, 2000 and 2016 — the researchers report an 80% chance that another slightly less popular candidate will win the presidency in the next 60 years if elections continue to be as close as they have been in recent decades.

Those are some pretty good odds. In fact, the researchers estimate that if someone loses the popular vote by within 1%, or 1.3 million votes, he or she has a 45% chance of winning the election. It has nothing to do with who the candidates are, the researchers emphasize, but the trend favors Republicans, who are estimated to benefit from future inversions 77% of the time.

So, we asked Geruso and Spears what this could mean for future elections and the future of the Electoral College:

Q. If the likelihood of an inversion is so high, why have we (U.S. adults) only witnessed it twice in our lifetimes?

We’ve had few inversions primarily because we’ve had few elections in our lifetimes. Over 40 years, there are only ten Presidential elections. In small samples it’s really difficult to know what the underlying probabilities are. If you flip a coin just 10 times, and it comes up heads twice and tails eight times, that’s not so improbable, even if it’s a fair coin that should come up heads 50% of the time on average. That was the challenge that we set out to meet in our project: To uncover whether the two inversions we’ve seen in 2000 and 2016 were probable events or statistical flukes.

Q. Why are Republicans more likely to benefit from an inversion election?

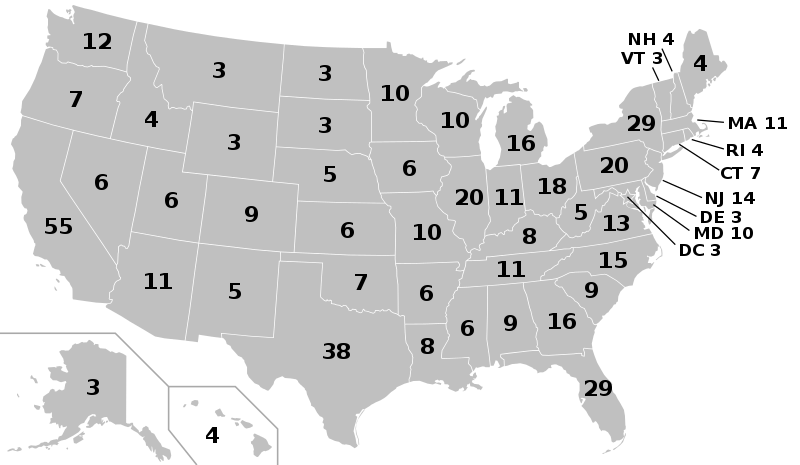

Today, Republicans are more likely to benefit from an inversion primarily because each state’s representation in the Electoral College is equal to its number of U.S. Senators plus its number of U.S. Representatives. For a small state like Wyoming, which has one U.S. Representative, the addition of the two Senators to its Electoral College delegation has a big impact on the state’s representation. It means that each individual citizen vote corresponds to a greater share of the Electoral College for Wyoming than for a large state like California and Texas.

Because, by and large, small population states lean Republican, this feature benefits Republican candidates. Interestingly, we calculate that if you removed the two Electoral College ballots corresponding to Senators, it wouldn’t reduce the probability that an inversion occurred. But it would change the partisan balance, replacing likely inversions that would favor Republicans with likely inversions that would favor Democrats. The balance shifts to become close to equal, but the inversion probabilities would remain.

Q. What are some examples of close elections that didn’t end in an inversion? Why do you think this was avoided?

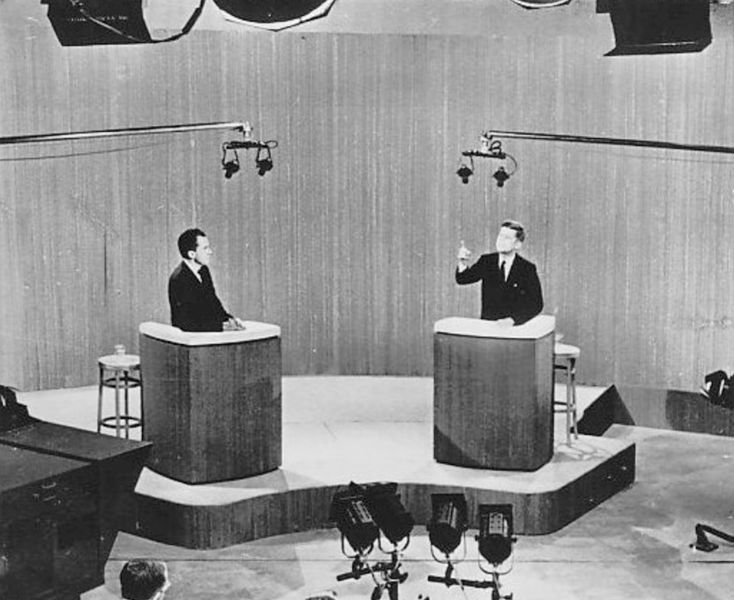

1960 is an interesting case. In the most-commonly-told history of the 1960 Presidential election, John Kennedy defeated Richard Nixon in the Electoral College and narrowly won the national popular vote by a little over 100,000 votes. Arguably, however, Nixon received more votes than Kennedy did. On the ballot in Alabama, voters selected electors directly. There were many Democratic electors: some who were loyal to Kennedy and some who were running precisely to oppose Kennedy. If voters for these anti-Kennedy electors are not counted as popular votes for Kennedy, then one published tally shows Kennedy losing the popular vote to Nixon by about 60,000 votes despite winning the Presidency.

That underlines just how fundamentally weird the Electoral College is. As a matter of fact, it is difficult to know whether Kennedy won the popular vote in 1960 because we don’t know how to count votes in Alabama in 1960 because voters weren’t directly casting a ballot for Kennedy or for Nixon.

More broadly, the distinguishing feature of elections that don’t end in inversions is that they aren’t close in the national popular vote. Inversions don’t happen in landslide victories. But in a close election, they are highly likely.

Q. Do we have a higher probability of experiencing an inversion election now than at any other point in history?

The probability of inversion is very tightly linked to the expected closeness of the race. If you look at the periods in history where we’ve had close races, that’s where you’ll see inversions. And the last couple of decades have featured some of the closest Presidential races in U.S. history. To the extent you think 2020 will be a close race, you should be prepared that an inversion is likely. That goes for any future election as well.

Q. Given that the chances of voting in an inversion election in a lifetime is more than 80%, should we reconsider our electoral system?

As researchers we wanted to discover and communicate these statistical facts about the Electoral College so that Americans could make their own informed decision on ongoing policy activity like the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC). The NPVIC would transform the electoral system, without repealing it and without changing the Constitution, so that the popular vote winner becomes President.

Ultimately, each American needs to decide these issues for themselves. But we don’t think anyone should make that decision without first understanding just how likely it is that if nothing changes, we will experience more and more mismatches between the popular vote and the Electoral College outcome.

Q. How would changes to the Electoral College influence the chances of an inversion election?

It turns out that no change to the Electoral College, other than a national popular vote, would eliminate electoral inversions.

The University of Texas Electoral College Study team simulated outcomes under alternative aggregation rules, including changes to state law. One set of simulations eliminated the two elector ballots that each state receives for its Senators. This would make the number of electors in each state more proportional to population. A second change allocated each state’s Electoral College ballots in proportion to the state’s popular vote (up to the nearest whole ballot), rather than awarding all Electoral College ballots to the (possibly narrow) winner of the state.

The exercise clarifies what contributes to inversions: For example, is it primarily about the disproportional voting power of voters in small states? We find that neither change would eliminate the risk of inversions in a close election. Eliminating “winner-takes-all” would cause a larger decline in the chance of inversions but would increase partisan bias — almost all inversions would be won by Republicans. Both changes together leave in place high probabilities of inversions in close elections.

How could inversions still happen? Because many factors contribute to inversions. Popular vote totals depend on the number of voters, but electors are allocated based on the number of persons in the last census — including children and adults who cannot vote. In short, relying only on a national popular vote would eliminate the chance of mismatch between the President and the popular vote winner.