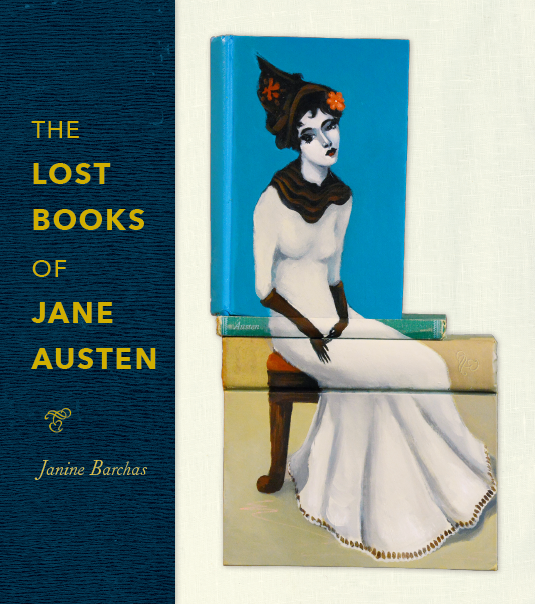

In The Lost Books of Jane Austen, Janine Barchas explores the burgeoning popularity of Jane Austen’s novels beginning in the nineteenth-century. Through photographs and unique historical perspectives, Barchas shares some of the earliest and cheapest reprints of Austen’s work that brought the author recognition in the working-class, leading to the reputation she has today.

Learn more in our Q&A with author Janine Barchas, the Louann and Larry Temple Centennial Professor in English Literature.

John Hopkins University Press, October 2019

By Janine Barchas, Professor, Department of English

How was Austen’s reputation reshaped in the Victorian Era?

Jane Austen, born in 1775 and publishing during the 1810s, was a stranger to the moral restrictions of the Victorian Era, which officially started in 1837. Yet the Victorians refashioned Austen’s reputation to suit their starched ideal of a proper woman writer. For this Victorianizing of Austen, scholars blame the biographies by her relatives that promoted the genteel public image of “dear Aunt Jane” with a falsified (think airbrushed) author portrait in 1870 (created more than half a century after her death). The posthumous false portrait became so influential and ubiquitous that it now circulates on the ten-pound note. But in point of fact, some of the fussy adjusting and prettifying of Austen’s reputation may have been a reaction to her growing popularity among the hatless masses in cheap editions.

Where do you think Austen might be in history had her novels not sold for such affordable prices?

I tend to rely on facts and admit that even friendly hypotheticals make me nervous. All I can observe with confidence is that the cheapness of reprintings in the nineteenth century helped to promote and lock in the astonishing literary fame Austen now enjoys. However, and just between friends, might Austen have risen to the top of today’s literary charts if her stories had remained accessible only as rarified and expensive editions — such as was the case in her own lifetime? My gut says “no.”

Who was Richard Bentley and why was he so important in furthering Austen’s renown?

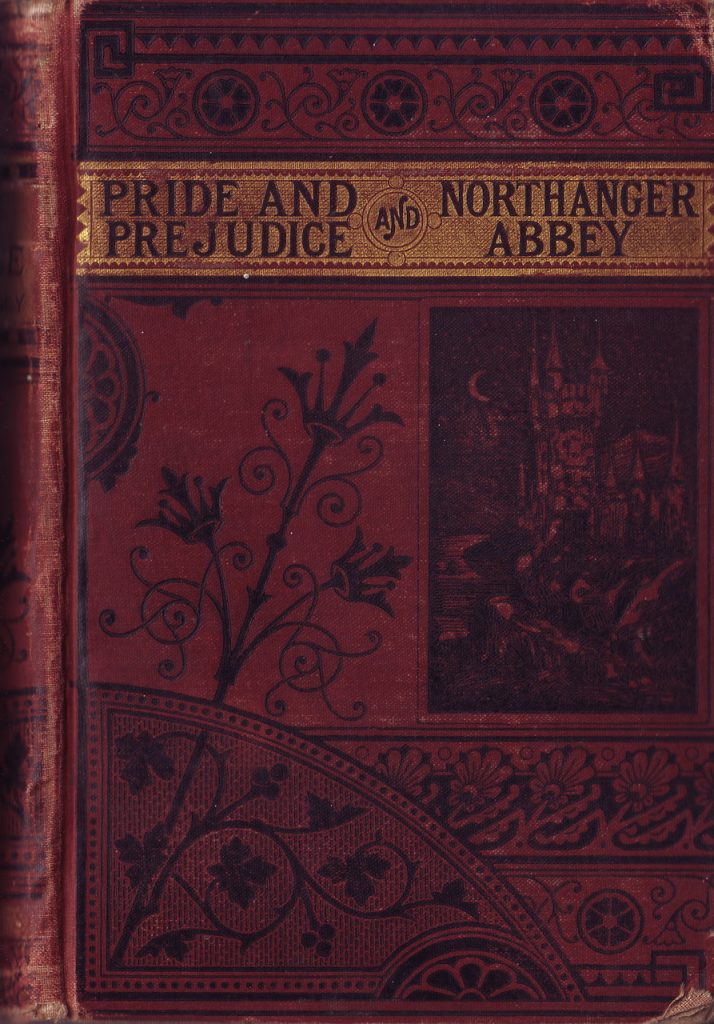

London publisher Richard Bentley (1794-1871) is widely hailed as the Prince Charming of Austen’s reputation. Bentley awakened the slumbering public interest in Austen when he reprinted her, starting in 1833, as part of his “Standard Novels” series. Each novel was priced at 6 shillings in a single-volume format. I, however, argue that, although Bentley’s elegant volumes proved important catalysts, they were not as accessible or “cheap” as his advertisements have (mis)led scholars to believe. Instead, I focus on the far cheaper and lesser-known Austen reprints of his competitors, who were newly targeting the working classes with far cheaper books (priced between ½ and two shillings) that sold at railway stations and bookstalls. However, precisely because of their intolerable cheapness and low production values these “lesser” versions were never systematically collected by scholarly libraries and, as a result, not studied or considered in the history of Austen’s reception.

Can you tell us about her readership during the 19th and 20th centuries?

I found evidence to suggest that, from roughly the 1840s to 1940s, Jane Austen appealed to a far broader readership than seems expected of her today — a readership that effortlessly crossed class, gender, age and national boundaries. By means of modern resources such as Ancestry.com and other online archives, I was able to trace the proud signatures in actual old copies to real men and women — who were members of the working classes as well as the educated elite, coal miners and domestic servants, school children and aging sea captains. The lives of these real readers offer depth and specificity to the standard reception history of Jane Austen, which flattens facts with references to a generic “nineteenth-century reader.”

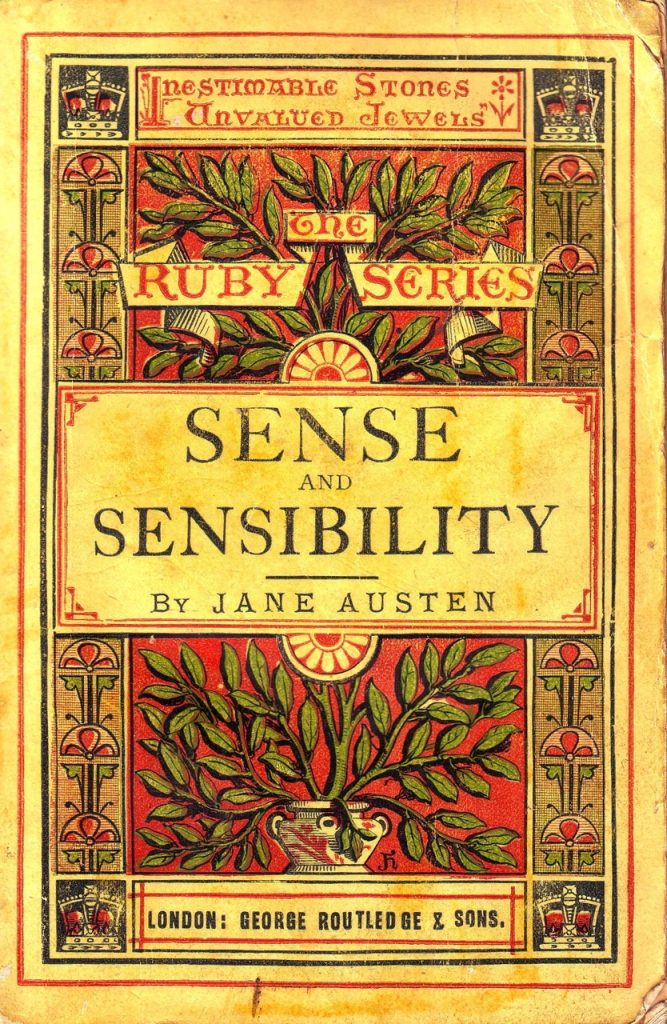

What was the reasoning behind Austen’s books becoming even cheaper ‘Penny Delightfuls’?

In the 1890s, penny editions aimed to provide the poor with better books than the sensational Penny Dreadfuls on which Britain’s lawmakers were then blaming the rise in urban crime. Two newspaper men, both towering figures in the publishing trade, William Thomas Stead (1849-1912) and George Newnes (1851-1910), reasoned that as long as better books cost close to a day’s wage, it was ridiculous to expect they would be bought by “the poorer millions.” Working in tandem, Stead abridged Pride and Prejudice for a mere penny while Newnes printed in two penny parts the complete text of Sense and Sensibility — its miniscule type requiring good eyesight. Physically, these penny editions were ugly little ducklings. Roughly stapled and glued, each unadorned text was printed in tiny type on cheap paper, resulting in books barely larger than a small modern paperback and a lot thinner. Penny editions of prose classics were seen as social improvement projects, intended to stimulate a “Reading Revival” among the working poor of worthy fictions.

How did you locate the editions that you share in the book?

Low-born books seldom make it onto the shelves of scholarly libraries at elite institutions, where rarity and authority go hand-in-hand. Instead, cheap books live the hard lives for which they were destined. This project began with a few survivors found floating among eBay offerings and other commercial sites. But locating books that libraries do not tend to preserve and that bibliographers do not always record proved hard. I needed to find private collectors with unorthodox tastes who might help a researcher they did not yet know. My project gained traction only after two private collectors, one in Texas and another in the UK, learned of my research through early publications and offered me access to their books. Only once I was able to benefit from their decades of collecting (40 years each!) did my own project truly take shape.

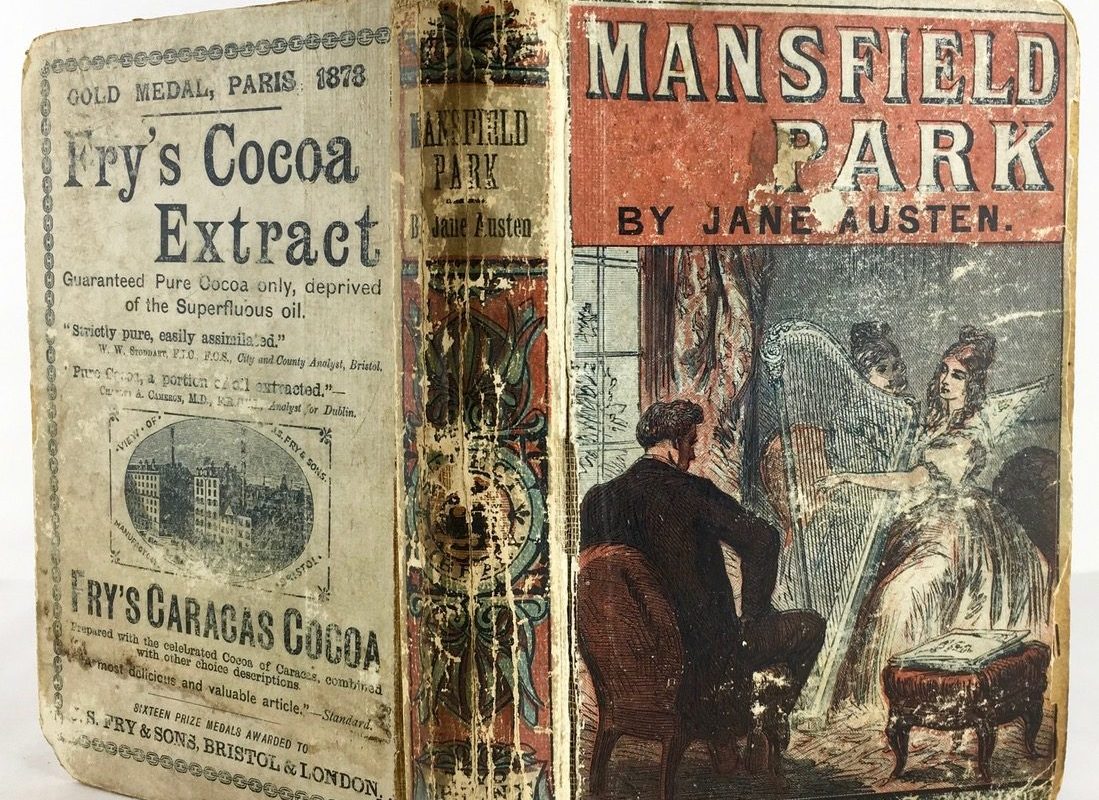

Of all of the Austen novels you were able to track down in writing this book, which was the most interesting find and why?

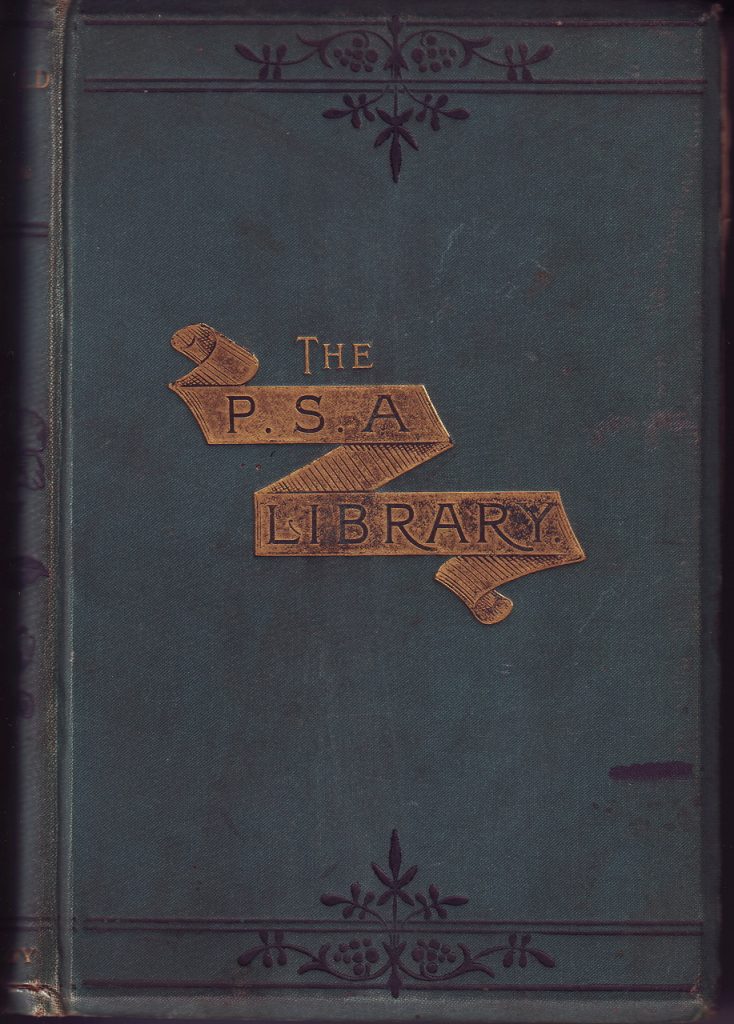

Perhaps one inexpensive 1890s edition of Mansfield Park, commissioned by the Pleasant Sunday Afternoon society of the Midlands town of Hanley and stamped with the “P.S.A.” logo, stands out as one of the most surprising eBay finds. This rare survivor proved a once-proud book trophy in a temperance society’s social club that was comprised of young coal miners and potters in an area of England whose heavy industrial pollution earned it the name of Black Country. All the Hanley members of the PSA society were laboring men, most of them performing the type of back-breaking work that did not require literacy. Jane Austen proudly being shared among dusty nineteenth-century coal miners, barrow loaders and clay blungers kinda blew my mind.

To learn more about Jane Austen visit:

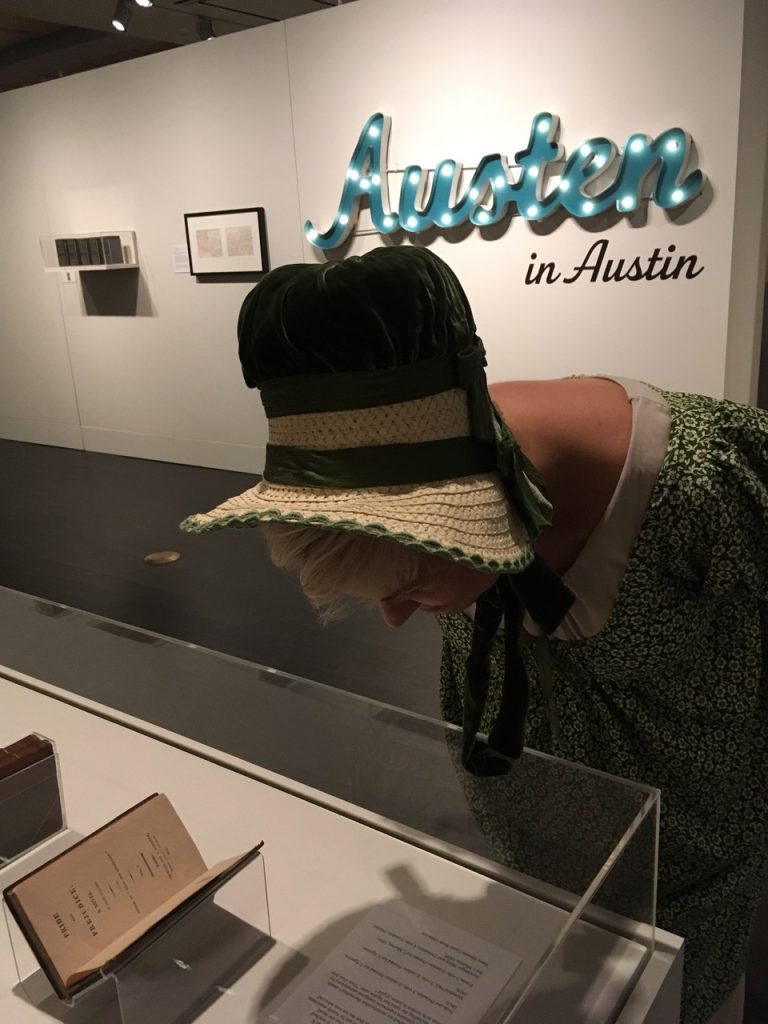

Austen in Austin

The Harry Ransom Center; “Stories to Tell” gallery on the ground floor

On view through Jan. 5, 2020

“I hope the exhibition will get folks thinking about whether research libraries should also make room for copies whose “importance” is of a different nature altogether— copies with a lowly provenance but a high impact on reception history,” concludes Barchas, who curated the Austen in Austin exhibition.