Mehdi Haghshenas’ signature course “What We See, What We Believe” focuses on critical analysis of media, but he begins the class with a meditation. For three minutes we all close our eyes and slowly breathe in and out. When the meditation is over, Haghshenas says quietly, “You are in the now.” And he’s not wrong. I was almost late to observe his class and ran the last two blocks, cursing the unreliability of Austin’s public transportation the whole way, but now I’m calm and ready to pay attention with only the faintest urge to check my email.

These meditations will employed on and off throughout the semester, but just two weeks in they already seem to be having a positive effect. Haghshenas addresses the room in a soft, non-authoritarian voice, but the hum of pre-class conversation vanished the moment he suggested we begin the meditation. Students shush each other in the rare instances when peripheral conversations threaten to encroach on the communal discourse. Today’s class is a group discussion, when students have the opportunity to present the readings and films they’ve been studying thus far. They’re organized, articulate and they’ve actually done the reading. Did I mention this is a group of mostly first-year students many of whom are taking the class to fulfill a requirement?

Signature courses are part of the university’s core requirements and their goal is to strengthen students’ skills in areas like writing and critical thinking while also exposing them to subjects that may be outside of their planned area of study. This means that classes are often composed of students from fields other than the liberal arts. Haghshenas, a senior lecturer of sociology at UT Austin, welcomes the opportunity to engage with such a diverse population.

“They come from different backgrounds, races, cultural heritages, and social classes,” he says. “Some of them are interested in science, some of them are interested in the liberal arts. But somehow we find this unity in diversity that encourages them to think and to open their minds no matter what perspectives they have.”

Haghshenas received the Holleran Steiker Award for Creative Student Engagement in 2017 and, more recently, a Student Council Endowed Teaching Award. He is especially proud of the latter, he says, “Because it came from the hearts of those who matter the most.”

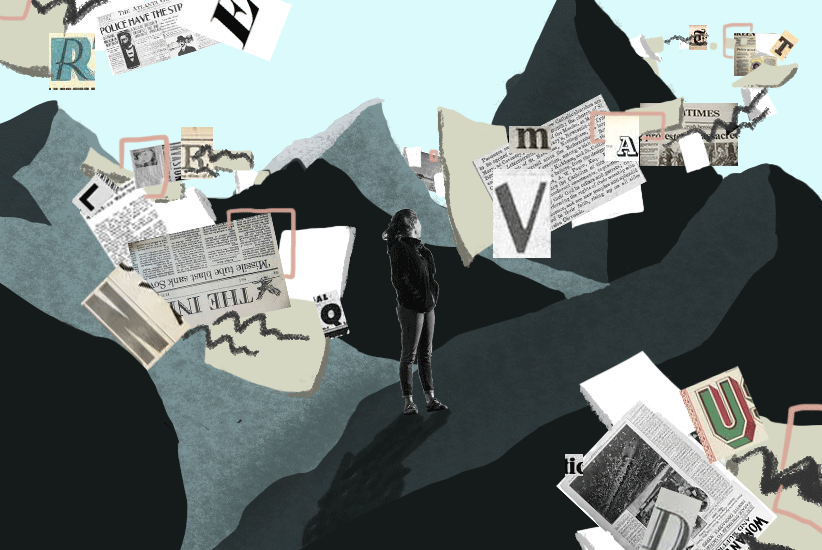

Over the next few months, Haghshenas’ students will learn how reality is socially constructed and examine the many ways in which media content shapes our perceptions and opinions and determines where we focus our attention. This includes everything from how news outlets’ hyperbolic coverage of violence paints an inaccurate picture of relative dangers (Americans are far more likely to die of heart disease than from anything as headline worthy as a terrorist attack) to the stifling nature of rigid gender norms and unrealistic beauty standards to the ways in which racism is built into our very language.

Special emphasis is placed on how these topics affect students outside of the classroom and how they can live less stressful and more rewarding lives by questioning some of the messages they receive from various media.

“Reality is an agreement we make at any given time.” Haghshenas explains.

We can’t and shouldn’t try to separate ourselves from society, he stresses, but we can be more aware of the fact that much of what we accept as “true” is shaped by people who don’t always have our best interests at heart. Take for example the so-called crack epidemic of the 1980s, which the class reads about early in the semester. While crack did cause real harm in poor urban areas, it never posed the threat to average suburban Americans that was portrayed in the news of the time. Nonetheless, politicians used the scare to win votes and public support for policies that exacerbated our mass incarceration crisis without addressing any of the underlying issues that contribute to drug use in vulnerable populations.

The class discussion I observe covers the crack panic and other instances in which established media outlets uncritically reported information from government officials that would later be proven false. One student comments that reading about this has caused them to lose faith in the media. Haghshenas, however, cautions against abandoning the idea that news sources can be accurate.

“Don’t lose faith,” he advises. “But use critical analysis.”

Another student points out that it helps to get information from multiple news sources. Still another reminds the group of the importance of reading beyond the headlines, citing examples from the course material in which dissenting views (with more accurate information) could be found if readers moved past the front page. The class is using what they’ve learned to collectively build a more comprehensive knowledge, which is one of the goals of these discussions. Part of Haghshenas’ approach to the teaching of critical thinking is helping students uncover and articulate what they already know.

I’m generally skeptical of the term “mindfulness” as it is frequently used by new age charlatans selling overpriced yoga pants and healing crystals. Before talking with Haghshenas, I would have thought it an odd pairing for critical analysis. But it turns out the two practices have something in common — both are ways of stopping to pay attention, whether to the implications of media messaging or simply to the present moment. During the pre-class meditation Haghshenas says, “We take nothing for granted.” At the time, I took this to mean appreciating the moment we’re in. But an equally accurate interpretation might be a call to rational thought, to scrutinizing information presented to us rather than passively accepting it as fact.

Haghshenas’ combined focus on critical analysis and mindfulness aims to make students not just more cautious consumers of media, but also better people. Education, he feels, too often focuses on competition and self-advancement, on getting the right job after graduation.

“A living curriculum should also encourage human values,” he says. “Self-confidence, responsibility, compassion, community service, and good character. Just as the end result of true knowledge is to develop wisdom, the end result of education is to develop character.”