At first glance the town looks like a Norman Rockwell painting come to life. It’s rather corny, this Anytown USA, a place where Aunt Bee bakes apple pies and Andy Hardy falls in love. But take a closer look. There is evil afoot.

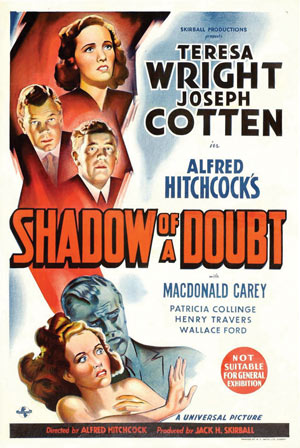

The town is Santa Rosa, California, chosen by director Alfred Hitchcock to serve as the setting for his 1943 psychological thriller, Shadow of a Doubt.

It was a deliberate choice, this idyllic town where Hitchcock introduces us to the wholesome Newton family and their bored teenage daughter, Charlie, namesake of her beloved uncle, Charles Oakley. Young Charlie is thrilled when her charming, worldly uncle pays a visit, but as the story unfolds, she soon discovers that her sleepy little town now harbors a heartless killer — her dear Uncle Charlie.

One could watch this film as an entertaining thriller and leave it at that. But there is so much more to be learned — about ourselves and the world around us — if we view it through a liberal arts lens.

Donna Kornhaber, an associate professor of English at UT Austin and a nationally recognized Academy Film Scholar, recalls a scene in Shadow of a Doubt in which Uncle Charlie, portrayed by Joseph Cotten, reveals his true nature and all but confirms to his niece that he is the “Merry Widow Murderer” sought in a nationwide manhunt.

At the dinner table Uncle Charlie describes rich widows as “useless…you see them in the hotels, the best hotels, every day by the thousands. Drinking the money, eating the money, losing the money at bridge. Playing all day and all night. Smelling of money. Proud of their jewelry but of nothing else. Horrible, faded, fat, greedy women…”

Kornhaber observes that during this speech the camera slowly moves from a wider shot to a closer shot of Uncle Charlie, and then stops. At this point young Charlie, off camera, interjects, “They’re alive. They’re human beings!”

Turning his face directly to the camera, her uncle coolly responds, “Are they?”

The camera cuts back to the niece. The uncle continues: “Are they human or are they fat, wheezing animals, hmm? And what happens to animals when they get too fat and too old?”

The words are chilling, but understanding the context of the film — when it was made, who wrote the script and why the director chose a certain camera shot — reveals layers of deeper meaning that are beyond words alone.

“Hitchcock makes sure we’re looking directly at Uncle Charlie in this moment. It’s for a reason,” says Kornhaber. “A lot of film classes or textbooks will note how the scene shows Hitchcock focusing our attention…well yes, but why? It has to do with history, literature, sociology, psychology…there are so many aspects of the liberal arts that actually plug into that moment. With a liberal arts education, you are well equipped to really unpack and unlock that moment.

“If you think about the conversation that the film is having, and think about how Hitchcock later filmed the Nazi characters in Notorious — revealing an outright barbarism in characters who seem pretty civilized on the surface — there’s a whole discussion to be had around what true depravity can look like, and what it means to dehumanize other people…That conversation is happening cinematographically in Hitchcock, but you have to understand the context to really see it. You have to have some literacy in Hitchcock, you have to understand it’s 1943 and you have to understand that Uncle Charlie is, metaphorically, a Nazi.”

As Kornhaber points out, it helps to know that Shadow of a Doubt was written by Thornton Wilder, who also wrote Our Town, a play that ends with a monologue from a young woman who sees life differently after she dies: “We don’t have time to look at one another…All that was going on in life and we never noticed.”

“Hitchcock amends that to say, ‘Well, if you really stop and look at your Uncle Charlie’…he literalizes that process, understanding that we’re not going to like what we see,” says Kornhaber. “It’s something he learned from the expressionists. We stop and look at Uncle Charlie, and Uncle Charlie looks right back at us. We cannot avoid looking at him in this terrible moment, and it’s for a reason.”

While a war against the Nazis raged in Europe, Hitchcock reminded moviegoers that the same evil could exist in our own seemingly safe communities. Kornhaber references the detective at the end of Shadow of a Doubt, who tells young Charlie, “Sometimes [the world] needs a lot of watching. Seems to go crazy every now and then. Like your Uncle Charlie.”

Why Film Matters

What students can learn through deep study of such a film is almost limitless. They can explore moral and societal issues, such as the nature of evil, how to recognize it and how to address the complexities of confronting it. The film itself is an artifact of history, offering insights into how a person during the war years of the 1930s and ’40s might have come to understand fascism, or the dehumanization of certain populations.

“With a liberal arts education, you have a lot of tools that you can use to approach film and to analyze the meaning of the filmic image. Students can unpack a film’s visual construction, explore its genealogy and implications, and draw conclusions as to its social, historical and intellectual resonances,” says Kornhaber. “They are able to engage in ways that leverage what they’ve learned in other liberal arts classes, and in so doing come to better understand visual storytelling, recognizing what it is that you can do in film that you cannot do in literature. You can study film by identifying shots all you want. You can do the anatomy of film forever, but students who draw from the liberal arts are especially well equipped for getting to the meaning, to the ‘why’ behind those shots.”

With a liberal arts education, you have a lot of tools that you can use to approach film and to analyze the meaning of the filmic image.

Donna Kornhaber

More than a dozen scholars across the College of Liberal Arts are delving into the “why” of films in a variety of disciplines including English, history, government, languages, area studies and ethnic studies. What they do differs from film academies that teach students how to make films. Rather, Kornhaber and other liberal arts scholars study films critically as the major art form of the 20th and 21st centuries — not unlike the study of literature in the 19th century. For a liberal arts student, and any college student for that matter, an understanding of our visual culture and its origins is indispensable in this global age.

Sabine Hake, professor and Texas Chair of German Literature and Culture in the Department of Germanic Studies, has examined how film helped usher in the global age in the 20th century and cites as an example Ernst Lubitsch, who starred in and directed dozens of films in Germany before heading for Hollywood in the early 1920s.

“What attracted me to Lubitsch was how he represented a trans-Atlantic, transnational perspective in the study of culture,” says Hake. “If we look at how culture developed in the 20th century, it was really the end of a national framework for everyone. Film, and specifically silent film, was international. Few even knew where these films were made.”

She says there was considerable optimism that this young medium could even promote world peace and understanding, not unlike the optimism people felt about the internet at the end of the 20th century, when it was viewed as a tool of empowerment for previously marginalized groups.

“The internet is almost a replay of what happened with early film, or with early radio, and the relationship between technology and democracy and the question of who owns the channels,” says Hake. “That’s a good reason why we need to study film, and especially the beginnings. Beginnings are always fascinating because they always raise the same hopes and fears.”

In following the trajectory of film development, one can actually gauge the ebb and flow of nationalistic and other political movements in the 20th century and beyond. “There was a turn to a more national perspective during the interwar years, which corresponds to political developments,” observes Hake. “Then after World War II, Hollywood became the most important weapon in the Marshall Plan and in the democratization of Europe.”

Changing Hearts and Minds

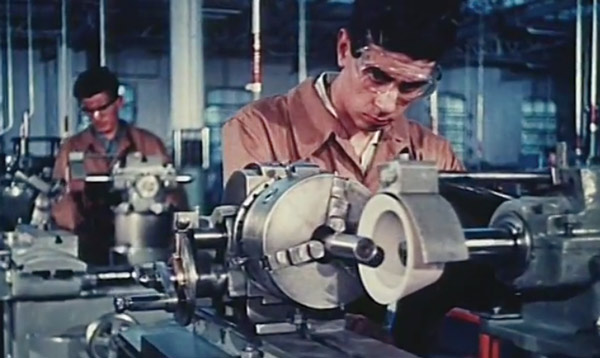

Paola Bonifazio, an associate professor in the Department of French and Italian, says there was an overwhelming production of short films after the war aimed at promoting a certain idea of modernity and industry to Europeans. In her book, Schooling in Modernity: The Politics of Sponsored Films in Postwar Italy, she examines how the Marshall Plan — through which the U.S. provided billions of dollars in economic assistance to help rebuild postwar Western European economies — directly aided the production of films that promoted the positive aspects of modern industry and individual freedom to Italian workers and citizens. There were two primary government agencies that produced films for Italians — one from the U.S. and one from Italy — but the same private Italian producers worked for both.

Although these films were state-sponsored, Bonifazio sees them as educational rather than as a form of indoctrination. “In the transition from fascism to democracy, it is precisely about the way we should understand the power of these films on people,” she says. “The sense is that you don’t want to indoctrinate, you want to educate. But education is fundamentally a way to create a power relationship with the audience. The films gave a role to the viewer, one of participation rather than simply absorption of information.”

Although economic revival and democratization were goals shared by American and Italian authorities, the films also reveal the social and cultural differences of the two societies.

The films gave a role to the viewer, one of participation rather than simply absorption of information.

Paola Bonifazio

“Overall, the films are homogenous in promoting modernity as a way to better the country and the individual, and since all the films were produced by Italian companies, they look very much the same at the surface,” observes Bonifazio. “But if you look carefully, American-sponsored films promoted an idea of modernity that was rooted in the idea of self-help, of the self-made man, a very American ideology.” On the other hand, Italian-sponsored films — even if they were directed by the same people who worked for the Americans — emphasized the state as the main entity responsible for the betterment of the citizen, she says.

The films had a big influence in modernizing Italian society, as did early television commercials in the late 1950s and early 1960s that mimicked the style of the Marshall Plan films. Bonifazio makes her point with a simple bouillon cube.

“Modernization took place especially in terms of lifestyle. The changes happened at both the structural and cultural levels,” she says. “You have a commercial for broth in a cube — no one in Italy would have dared make broth from a cube before the war, but in the commercial it is attached to a certain lifestyle, which makes you, using the cube, not some bad housewife who is not able to make her own broth, but some glamorous woman who doesn’t have the time to do it.”

Moving Images

What the bouillon cube demonstrates in its small way is the very large effect moving images have played in our lives during the past century. In her book, Screen Nazis: Cinema, History and Democracy, Hake points out that the 20th century was the century of film “and the kind of mass mobilizations that gave rise to fascist movements as well as modern democracies.” She writes that “the emotions engendered by film have been used throughout its history to build and maintain support for dictatorial regimes and their oppressive policies…yet the same strategies — of course, employed more subtly — can be found in stories, sounds and images created to defend and promote democracy.”

Indeed, as Bonifazio observes, the short films produced by the Allies under the Marshall Plan share similarities to those produced under the Italian Fascists. “They used some of the same directors that had worked with (Benito) Mussolini,” she notes. “In comparing the films you can see continuities between the idea of a welfare state before and after the fall of the regime, and the way in which the state is behind individual betterment. Visually they are very similar, like the muscular worker in the factory, and armies of marching workers. Through these images they made a transition from warfare to workfare.”

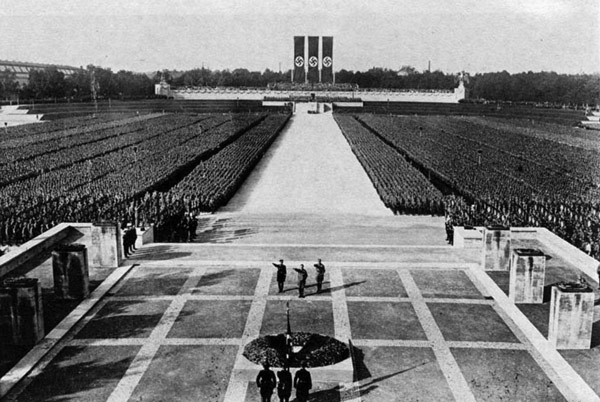

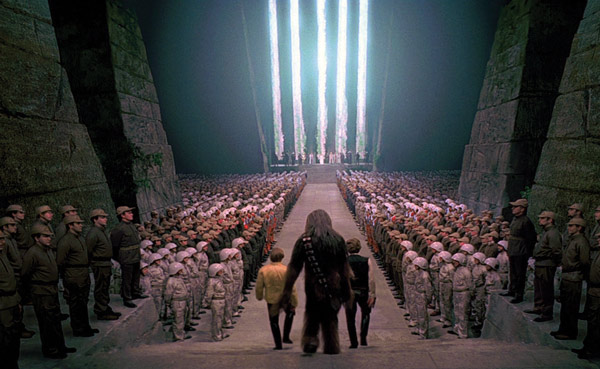

The Nazis used the moving image to great effect before and during the war, most notably Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will — a 1935 propaganda film that highlighted a massive Nazi Party Congress rally in Nuremberg. “It scared the hell out of me,” remarked Hollywood director Frank Capra. “It fired no gun, dropped no bombs, but as a psychological weapon aimed at destroying the will to resist, it was just as lethal.” Triumph would eventually inspire Capra to produce a seven-part Why We Fight film series aimed at persuading Americans to support U.S. involvement in the war.

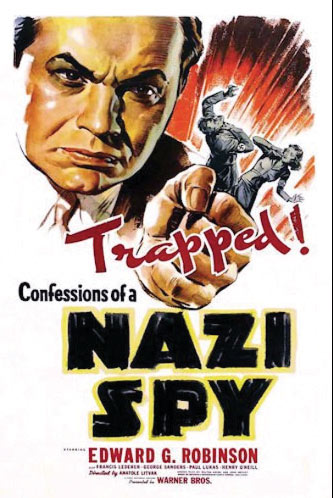

During and after the war Hollywood produced a slew of mostly B-grade anti-Nazi films that forcefully affirmed American values. “On the most basic level, the anti-Nazi films represent Hollywood’s response to what the Nazis in 1933 had announced as a fundamental new approach to politics as a series of tightly scripted media events and highly emotional mass experience,” writes Hake in Screen Nazis. “As the most visible manifestation of such uncanny effects, the antagonistic figures of Nazi and anti-Nazi became the central organizing principle in the self-representation of American democracy during WWII.”

[Students] need to be trained to see how images communicate feelings, tell stories, organize identifications. Being visually literate is absolutely essential to function in our world.

Sabine Hake

Hake notes that some films used humor to mock Nazi leaders, most notably Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator (1940). Humor was also deployed in animated shorts such as Disney’s Der Fuehrer’s Face (1942), in which Donald Duck has a bad dream about being a Nazi armament worker (Kornhaber discusses The Great Dictator in her first book, Charlie Chaplin, Director, and she covers Donald’s wartime adventures and many other types of war-related animation in her upcoming third book, Nightmares in the Dream Sanctuary: War and the Animated Film).

Films are the most powerful way to define how we feel about being part of a country with a particular history, observes Hake. “Literature used to have that function for an educated elite in the 19th century, but in film we have all the important connections between narrative history, nationalism, patriotism, globalization. It is important to teach film because students need to be visually literate. They need to be trained to see how images communicate feelings, tell stories, organize identifications. Being visually literate is absolutely essential to function in our world.”

Understanding Your Moment

“When you learn the language and the vocabulary of film, and when you come to understand that there is such a thing as visual grammar and visual diction, then you have real power, because you can begin to understand how images are operating on you…and that power is not just available to you as a spectator: You can carry that literacy into your life, into your profession, into your citizenship,” says Kornhaber. “Once you’ve gained that power of visual literacy, you never lose it. And that’s incredibly important, especially now, when everybody has something flashing at them at all times from their phone or their watch or a billboard or computer.”

Understanding narrative from the inside out is a critical asset in today’s world across multiple professions, she adds. “When you learn how to close read a film, you’re not just learning how a particular director is communicating. You are also learning how you yourself can communicate visually and how to understand and articulate what you see in visual culture. As in all the liberal arts, you are put into conversation with great minds, with a variety of people who have something important to say — they’re just saying it visually, cinematographically. Once you know how to approach it, studying film can really test you and help you to grow, to empathize, to better understand history and to better understand your moment right now.”

That also applies to the short educational films Bonifazio has studied. “Some of these short films are strikingly similar to the neorealist films of the time,” she says. “By teaching other cinema — that is, non-commercial cinema — in relation to fiction-based cinema of the same period gives a different perspective not only on the historical meaning of a film but also on the history of film itself.”

Understanding our moment through the history of visual media is of utmost importance to students, says Hake. “This is our culture today. It is important students know how it came about. It’s important to know how it situates the United States, the vision of America, in the world. And it has an incredibly important economic dimension; because the media landscape is global, we are no longer in the Hollywood-dominated century, and so despite globalization, national differences remain.”

She says there is a “groundswell” of frustration with globalization these days, as people seek a return to closed borders and a new embrace of ethnic identities. “Even from the political perspective, it is really important to see how films will validate that,” Hake says, observing that in her own home country she sees an increasing rejection of American films and television series in favor of storytelling based in Germany and on German themes.

“The study of film through the liberal arts will be indispensible to students who will need to interpret and navigate this new world,” says Kornhaber. “Studying literature or photography can also do these things, but film is narrative through imagery, photography plus time. It can speak through a visual vocabulary that can, in the best cases, communicate in ways that exceed words and language. Film offers an amazing gateway into a deeper understanding of our larger contemporary cultural moment.

“If the purpose of the liberal arts is to submit to disciplined inquiry all the facets of human culture and society, then the liberal arts cannot exist without the study of film, lest it wish to become a study only of human culture as it existed in forms that predate the year 1895,” concludes Kornhaber. “Students come to college to try to better understand the world they are about to enter as postgraduate adults, and to learn the skills of analysis and interpretation that will help them navigate that world.”

Not a shadow of a doubt about that.

Recommended Reading

Screen Nazis: Cinema, History, and Democracy Routledge, University of Wisconsin Press, Aug. 2012 By Sabine Hake

Schooling in Modernity: The Politics of Sponsored Films in Postwar Italy University of Toronto Press, May 2014 By Paola Bonifazio

Nightmares in the Dream Sanctuary: War and the Animated Film University of Chicago Press, Dec. 2019 By Donna Kornhaber