Photos by Robert Lemon

Much like the government, the railroads, farmland and cities, the United States food truck industry was built on the backs of immigrants.

“The Mexican food truck changed how we looked at our cities,” argues Robert Lemon, an expert in urban geography with a bachelor’s and doctorate from The University of Texas at Austin.

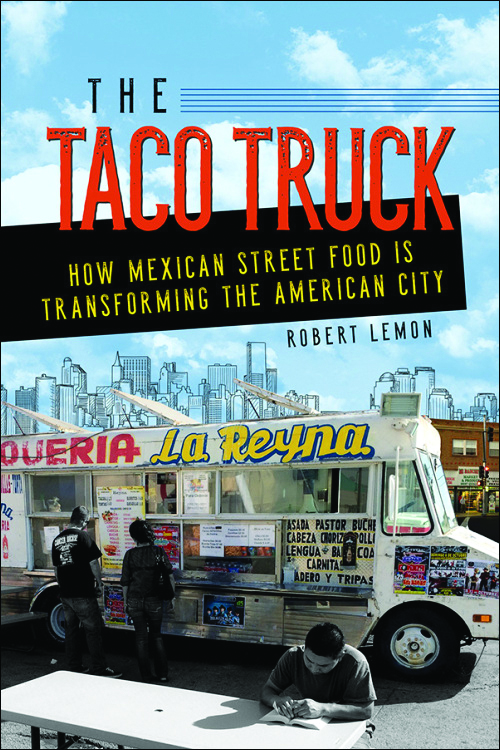

Lemon’s book, The Taco Truck: How Mexican Street Food is Transforming the American City, examines the evolution of the taco truck, from its humble beginnings as fast food for the immigrant working class to today’s millennial-driven, multibillion-dollar mobile food industry.

It is a culmination of five years of research on taco trucks and insightful interviews with taqueros, or taco chefs, and communities across the U.S. While that may sound delicious, Lemon’s interest in the subject actually piqued after a taco truck in Columbus, Ohio, left a bad taste in someone’s mouth.

“Some people saw them as eyesores, claiming they would attract crime,” explains Lemon, who worked with Columbus neighborhood services while earning his master’s at Ohio State University. “Taco trucks can spark a range of debates, from cultural perceptions of how public and semi-public space should be used to aspects of restaurant competition.”

To help incorporate the trucks, Lemon began visiting and getting to know their immigrant owners, how they were adapting to life in the U.S., and, most importantly, why they chose to sell tacos. Through his research, he unraveled the ethnic, class and cultural threads woven into the taco truck’s history and the public spaces they occupy across the U.S.

“Food has no meaning; the people around food give it meaning,” he says. “Our sociology around food shapes our cities — who our populations are, what they eat, how they talk about it. Those perceptions shape policy. They change who can eat what, where.”

Taco ’bout History

The taco truck first arrived on the American scene by way of migration — Mexican laborers traveling to regions such as Los Angeles in the early 20th century. Taking notes from mobile food vendors that came before — chuck wagons serving cowboys on cattle drives; lunch trucks serving workers at construction sites — the taquero would drive around to agricultural sites, serving up quick, affordable eats to laborers in the field.

“In this way, the trucks exemplify an aspect of foodways; estranged emigrants search for fond memories of home through food and through the taquero, who knows how to make such food,” Lemon explains.

Over time, the cost for taco delivery — gas, maintenance, driving time — began to add up. So, trucks began settling within and near California’s Latino neighborhoods, a change welcomed by working-class immigrants familiar with the idea of street food and hungry for a taste of home.

“Taco truck owners have produced a space to provide inexpensive comfort cuisine to an immigrant clientele. In so doing, they have found an economic avenue to tap into,” Lemon writes. “The taco truck’s design and function allows it to seamlessly integrate into the social fabric of Mexican immigrant communities.”

He adds: “Unfortunately, its practice does not always fit into the ways that many Americans wish to perceive their neighborhood spaces.”

A Beautiful City

Street food has been a part of Mexican lives for centuries, with roots as far back as the market of Tlatelolco in the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan (now Mexico City) where ancient people munched on tamales while sipping pulque — booze made from agave sap.

And although street food was widespread throughout the American Southwest in the 18th and 19th centuries, the U.S. has a long history of pushing out informal commerce. In his book, Lemon points to the San Antonio “chili queens” — “the most mystical Mexican street food vendors in the United States” — as a prime example.

In the late 1800s, a group of Mexican women cooked up some of the best chili around, dishing it out to crowds of tourists in downtown San Antonio. As their popularity grew — wide enough to be featured at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair — so did the efforts to disband them through excessive health regulations and criminalization. Eventually, “eating Mexican chili in front of the Alamo was deemed an indecent practice.”

“Cities sought to sanitize things,” says Lemon, describing the City Beautiful Movement, when city planning became more orderly and grand in hopes of promoting civic virtue.

The Taco Truck: How Mexican Street Food Is Transforming the American City

University of Illinois Press, May 2019

By Robert Lemon

Street vendors, however, had no place among the aesthetic: “Street food was a little bit of a mess — cluttered, busy, maybe a little unsanitary too. So, instead of regulating, they just wiped it out.”

Highways paved over slums, car traffic replaced foot traffic, and cities built tree-lined baroque boulevards to drive up property values and create the perception of a high quality through order and control. The practice was reinforced in 1982 by James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling’s “broken windows” theory, which postulated that minor forms of disorder, such as broken windows or informal commerce, underwrite neighborhood decline and reduce quality of life — a notion city officials have followed blindly without consideration as to what quality of life could mean for different people, Lemon argues.

“For most Mexican immigrants, traditional street food practices represent who they are as migrants from the developing world trying to make ends meet in a capitalism-driven society,” Lemon writes. “At the same time, vending tacos from a truck along the street may be seen by community members as threatening their own social identity. It is ultimately a cultural debate, and almost always an uneven one.”

Follow the Food

Like the chili queens, taco trucks became subject to a variety of rules, regulations and requirements in an effort to push them out of the city. At one point, Sacramento and Los Angeles required trucks “stay mobile” and move a half-mile every half-hour. Failure to do so would result in a fine or even jail time.

Though stringent for immigrant taco truck owners who were already feeling economically pressed and socially ostracized, these regulations created a unique opportunity for a younger generation looking to leave their mark on the streets.

“We’re seeing this renaissance, or resurgence, of people wanting to use their streetscapes.”

Robert Lemon

Enter Kogi, a Koreatown-born food truck business that fought against the discriminatory regulations with Twitter and trend-hungry millennials. At the end of its first year in 2008, Kogi grossed $2 million in sales by tweeting the truck’s location and dishing out hybridized Korean barbecue tacos to its tech-savvy clientele.

“People really took to it. They thought it was so cool to find and follow their favorite truck,” says Lemon. “This is how the food trucks could resist being zoned out of the city.”

While taco truck owners didn’t follow suit due to lack of technology and funds for more expensive, trendy foods, Kogi improved the food truck’s overall image, paving the road for the gourmet food truck movement. According to Forbes, the size of the food truck industry in the U.S. alone is estimated to grow up to 20% in 2019.

“We’re seeing this renaissance, or resurgence, of people wanting to use their streetscapes,” says Lemon, describing how taco trucks continue to reflect and contribute to the evolving character of their neighborhoods.

“The taco truck’s spontaneity makes the street a serendipitous urban landscape that harks back to the ways city streets originally functioned, before the advent of the car,” Lemon writes. “The street becomes pedestrian again, ironically through the socio-spatial practices of a motorized truck. But the taco truck’s nonconforming uses, its unpredictable qualities, and the chaos it supposedly induces disrupt, disturb and challenge the contemporary conformist concepts of the street and to whom the street belongs.”

Recognizing the value of such spaces, today’s city planners have begun “manipulating things to their advantage” by planning pockets of perceived spontaneity where food trucks can operate legally and attract free-flowing capital, while still maintaining control through heightened permit costs and increased regulations.

“Foodways, which were traditionally sluggish processes of social integration, are quickly becoming ways to sell a city as a multicultural playground,” Lemon writes. “Now that urban developers and city councils select culinary narratives to sell their communities, city planners and elected officials must be mindful for whom these narratives benefit.”