November 7th marks the 102nd anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution, but many questions about that pivotal event have been left unanswered, including those surrounding the remains of two other Romanov children, found in 2007.

The six-part docuseries The Last Czars (2019), currently streaming on Netflix, strives to answer some of these questions through its lively retelling of the turbulent and tragic period, beginning with the death of Alexander III in 1894 and ending with the execution of his son, Nicholas II, and his family in 1918.

Unlike other period dramas, which often recreate events using a more sensationalist and dramatic approach loosely based on the facts and realities of the time, The Last Czars aims to shed new light on some familiar, if misunderstood, historical figures, by challenging popular narratives and stereotypes about the Romanovs and that period in Russian history more generally.

With the help of British and American historians — myself included — who guide viewers through critical moments in Nicholas’ rule and provide analysis of the political and social conditions of the day, this “vivid and transporting documentary” draws the audience into the complexity of the events and compels us to see the historical figures as human beings driven by their own fears, obsessions, and calculations unfamiliar to modern viewers.

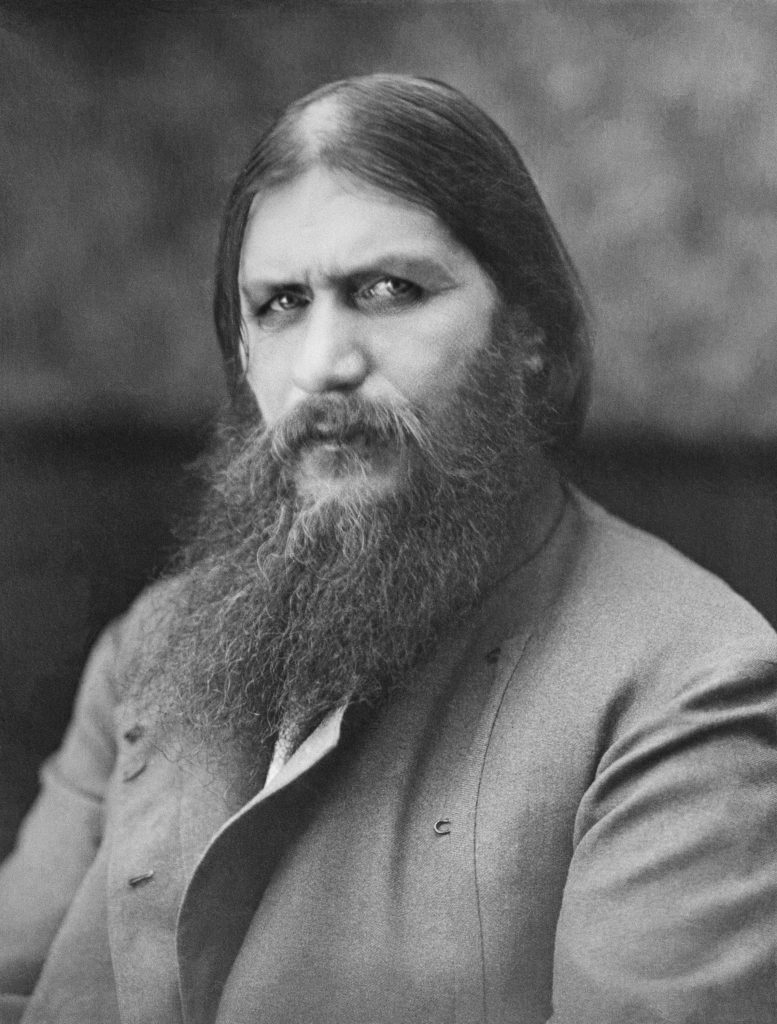

Take for example Nicholas II, who struggled to produce an heir, and then fought to keep secret the fatal illness of his son, Alexey, so he could maintain the appearance of a stable monarchy at the helm of a powerful Russian Empire. While not downplaying the scandalous behavior of the “mad monk” Rasputin, the series succeeds at presenting him as a true — if misguided — spiritual seeker with a strong sense of religious duty, who became something of a “personal Jesus” to the pious and mystically inclined Nicholas and Alexandra.

This more sober take on Rasputin serves as a welcome counterpoint both to the mainstream American view, particularly common among younger viewers, of him as a magician, partly based on his portrayal in the animated film Anastasia (1997), and to a recent revisionist trend in Russian media that, after decades of vilifying him, now extolls Rasputin as a spiritual leader and honorary saint, as seen in the recent big-budget TV mini-series Grigoryi R. (2014), rumored to be streaming on Amazon Prime soon.

While the royal family and its troubles are the centerpiece of The Last Czars, the story that frames all six episodes is the mystery of Anna Anderson, an enigmatic young girl confined to a mental institution in Berlin after attempted suicide in 1920. For decades, many fervently believed that she was the Grand Duchess Tatiana or Anastasia, one of the Romanov daughters, until a DNA test gave a definitive answer about her true identity.

However, despite these findings and the much-publicized interment of the last Romanovs in the Peter-Paul’s Cathedral in Saint Petersburg in 1998, the story of the last czars is not yet over. Currently, the Russian Orthodox Church opposes the burial of the remains of the other two children, Tsarevich Alexey and the Grand Duchess Maria, found in 2007, in the family sepulchre and demands a new round of tests to confirm the identities of all family members. So, there might yet be a new chapter in the Romanov story.

As someone passionate about teaching Russian history and culture, I greatly enjoyed this opportunity to share my knowledge of the period with a wider audience, and look forward to the secret history that will unfold with these new discoveries, Though a silver-screen sequel isn’t likely to happen for The Last Czars, one can only hope that the success of the docudrama would lead to the creation of more series in this hybrid genre, combining excellent entertainment, archival footage, and narratives by experts in the field.

Marina Alexandrova, Ph.D., is an associate professor of instruction in the Department of Slavic and Eurasian Studies at the University of Texas at Austin. She teaches a variety of courses in Russian language, culture, and history, and is currently working on a research project that explores the connection between the tsars and their spiritual advisors.